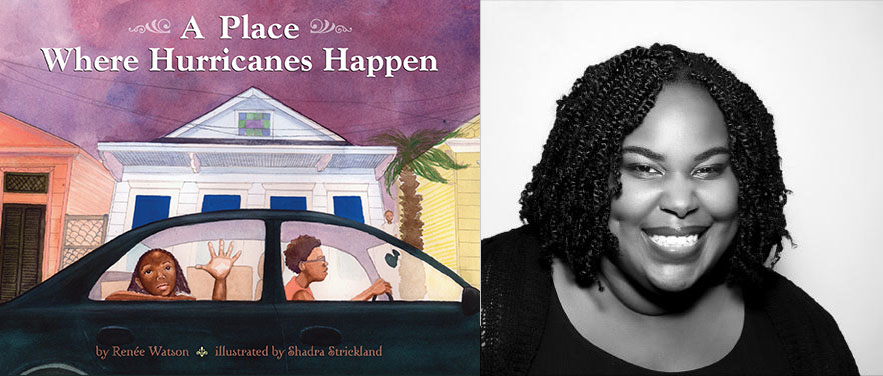

Renée Watson’s books include the YA novels Piecing Me Together, What Momma Left Me, and This Side of Home, which was nominated for the Best Fiction for Young Adults award by the American Library Association. Renée’s writing and teaching work aims to help youth cope with trauma and discuss social issues. Her picture book, A Place Where Hurricanes Happen, is based on poetry workshops she facilitated with children in New Orleans in the wake of Hurricane Katrina.

Ibi Zoboi is the debut author of the YA novel American Street, a coming-of-age story infused with magical realism about a Haitian immigrant who comes to Detroit. She has taught creative writing with the Sadie Nash Leadership Project and Teachers & Writers Collaborative, and she designed the Daughters of Anacaona Writing Project, a writing workshop with teenage girls in Port-au-Prince, Haiti. Ibi has also recently completed a teen fantasy novel based on Haitian myth and folklore.

Renée and Ibi sat down in November 2016 with Teachers & Writers Magazine Editorial Associate Maryana L. Vestic to talk about the writers, teachers, and stories that influenced them and how they seek to write, teach, and help young people find not only their inner strength, but their humanity as well. Part 1 of their joint interview appears below; part 2 will appear on February 20.

Teachers & Writers: How did you first meet?

Renée Watson: I was one of the lead trainers of Community-Word Project’s training for teaching artists, which is where I met Ibi. The summer we met, it was in the training on how to teach social justice. Ibi came, and we just connected.

Ibi Zoboi: I think later on I found out you had written a picture book, A Place Where Hurricanes Happen, and I had just started a writing-for-children program. We touched base here and there, but it wasn’t until about two years ago that we started hanging out with other writer friends.

T&W: Who are some educators who influenced you growing up, particularly in relation to creative writing?

RW: I owe so much to the teachers, good and bad. In the second grade, I wrote a 21-page story—handwritten—which I’m sure was really hard to read. My teacher saw a gift in me and said, “You’re gonna be a writer one day.” She would buy me journals. She talked to my mom and said, “Let’s get her in some summer writing classes and nurture this gift.” Even though after second grade I wasn’t in her class any more, she looked out for me. She was always checking in: “Are you writing? Let me read your poems.” So, at a very early age, I identified as a poet.

By high school, Linda Christensen was—hands down—my mentor. I look up to her so much because that was when I learned poetry could be much more than about seasons. She said, “Use your voice to say something. If you’re going to write, what are you going to write about?” I identified as a poet, but in high school I felt like, oh, there’s activism with writing. Those two things became very real and tangible. We would read a wide range of books and have to answer questions about race, class, gender. Our assignments would be to write short stories or poems or plays even, after whichever writers we were studying. So, my first YA novel, This Side of Home—I wrote it in her class as a short story. My neighborhood was being gentrified. No one was really talking about it, but I knew. This was 20 years ago. I knew that the changes weren’t for the people in the community. So I wrote this little short story about sisters who are on opposite sides, having an argument. I went back to it all those years later and turned it into a novel.

I look back on high school very fondly, along with the impact that teachers can have on you to be gatekeepers, to fan the flame of these small talents that you have, treat you seriously, and push you in a certain direction. I’m very grateful for that. What about you?

IZ: I had a fourth-grade teacher who said I was a journalist. We had to do reporting on school events. I loved it. It was back when we had to type the text, cut it, and paste it onto a larger paper, and I wanted to report on everything. She told my mother, “Your daughter is going to be a great journalist.” She wasn’t pushing me to write, but I still remember it to this day. And my mother remembers it. My mother still thinks I’m a journalist. It’s an immigrant thing. If you’re a writer, you must be a journalist!

I didn’t have really influential educators until college. I went to a predominantly white school and I remember not having anyone to take me under their wing. I didn’t stand out. I felt invisible until I left a private university and went to a CUNY [City University of New York] school, where something about that environment was more wholesome and grounded. There were older people in the classroom. There was diversity in the classroom. There was a spirit of activism.

I had a teacher who was an activist and writer. Back in 1997, there was something called the Yari Yari Conference at NYU. It was a conference for women of African descent from all over the world. I remember my professor pulling me aside. She pulled out her checkbook and a book by Octavia Butler. I didn’t know who that was then. She wrote a $50 check for me to attend a full day at Yari Yari Conference—to skip class! She paid for me to go and that changed my life. I always remember that to this day. It wasn’t just her saying, “Keep on writing.” She actually invested in me because she saw some potential.

T&W: Are there any works of writing or additional experiences that influenced and inspired you as much as these educators did?

RW: I grew up in Portland, Oregon. Very white city. Very white state. For elementary school, I went to a predominantly black school, but my middle school was predominantly white, over on the other side of town. A lot of the teachers were not prepared to have their school integrated, so they treated the students of color unfairly. After having these amazing teachers in elementary school, middle school was extremely rough. So, I think that influenced me too. The power of influence—knowing that you can impact a child’s life and plant seeds, good or bad—motivated me to want to do something with young people. I wanted to make sure as an educator that I allowed space in my classrooms and workshops for young people to be able to express themselves and use art as a way to talk back to the world.

I just had really strong examples of how to critique the world. How do we look at cartoons and think about gender stereotypes? What are the people of color doing? Who are the beautiful damsels in distress? What do they look like—skin tone, body size—all of that. Those are the conversations I was having at 14, 15, 16 years old. It was such a gift. I want to do that with young people. It wasn’t a piece of writing that inspired me, it was just the people. What about you, why did you start teaching?

IZ: I never really thought about getting into teaching. My love was writing, writing, writing. I needed to write. My first job was as an editor of a small weekly paper in Queens. At Hunter College, I was the managing editor of a paper called The Shield, which was a really political magazine for people of color in that school. I was a features editor for Hunter Envoy. Basically, my path was journalism. I really wanted to be an investigative reporter and I wanted to be in the Village Voice and the New York Times.

At a very young age, what was happening was that I wasn’t making any money. I started working for a newspaper and they would send me out on stories—I was doing human interest stories—I had to work and not get paid until the story was accepted. I’d write these articles and not get anything accepted. So, I started working in after-school programs while I was writing during the day—teaching creative writing in those programs where they have kids working on newspapers.

RW: I grew up in a family, in a community, and in a church that said, “I’m telling you this; now you go and tell the others.” It was kind of the norm, so when I think of being a teacher, it was just something we were expected to do. At church we had to teach Sunday school to the little kids, so I grew up very much always presenting and sharing my work in that way. There was a point where it became I can’t just love children. I have to have some skills. I need enough to come into public schools, especially, and just have fun with art. Too much is at stake, so I really needed to learn the art of teaching—really think about scaffolding lesson plans, emotionally and actually.

Especially for us, as a lot of the times we’re teaching social issues, heavy topics. So then, how do you think about class and culture, class and diversity, and what else is happening in the room besides the lesson? I became very hungry for getting my hands on anything, going to conferences, getting mentors that were doing this work. Reading people like Maxine Greene and working at DreamYard were very impactful on my teaching practice. Studying under people like Robyne Walker Murphy who just get this work and are passionate, but also skilled. There’s a craft I think that sometimes we don’t talk about. I think it’s equally important to be a good teacher and not just a good artist in the classroom.

IZ: I think after working with certain organizations, I realized what wasn’t working for me in terms of that teaching that you were just talking about, Renée. For a couple of years, I worked at an arts organization where they had a rites-of-passage program and they created their own curriculum. I got more into indigenous ways of looking at teaching vs. methodology, the pedagogy that we have now, even in the social justice curriculums.

It’s something I keep thinking about in my writing too. In the classroom now, where my husband is a full-time teacher, we’re realizing that there’s something missing where kids are graduating and still missing the soft skills and spiritual skills needed to navigate their particular world and their particular circumstances. I got into teaching and am writing books for teens and YA readers, and now I want to bridge that gap. You know, our characters are going through stuff in our books, but in the classroom, we don’t really get to examine their personal lives. So, how do we take the teaching practice and our creative writing practice and not necessarily teach creative writing, but teach life skills.

RW: Well, that’s why I think art is so powerful. I do think there is a missed opportunity a lot of the time when we come into the class and only focus on the craft of writing. When you’re talking to young people who don’t have a lot of control and power in their lives, and maybe feel hopeless, and you are helping them understand the power of revision: You made this, and now you can re-form it and reshape it and make it into something else. That is a skill, to stick with something, to take what works for you, but leave the rest—that’s a skill you’re going to need for the rest of your life! How do we have that conversation while simultaneously helping them develop their strong writing muscles?

I think I want to function where both are happening. I think my best teaching has happened when I’ve been able to pause for a moment and have that conversation with young people. Then get back to the poem. You may never really be a poet, you might not publish a book one day, but you’re going to be a citizen of this world. I want to make sure you are practicing empathy, reading characters that are not like you, and figuring out how to problem solve—all of those things that we call soft skills, but that are not. They are hard skills, necessary and crucial.

IZ: I think that was some of my frustration. I loved teaching, but to me, with pedagogy and methodology, I felt boxed in. I just want to take these kids on a journey for a minute! I’ve done it when I worked for an organization called Sadie Nash Leadership Project on a project called “Female Archetypes in World Mythology.” It sounds very heady, but I had high school girls examine what it means to be feminine—not a woman, but the idea of femininity and masculinity in indigenous cultures. I had a loose outline, but I know it was transformative both for them and for me as a teacher in allowing them the space to be some sort of incubator for self-healing and ideas.

I remember them reading a poem, Nikki Giovanni’s “Ego Tripping,” and I remember one girl challenging me. There’s a line in the poem where Nikki says, “I turned myself into myself and was Jesus/ Men intone my loving name,” and I wanted the class to talk about how they are powerful, how they are omnipotent, how they can be superhero-like. Not necessarily God-like, but superhero-like. This idea of writing a poem in that fashion came into conflict with someone’s faith. It blew my mind, because I realized I was coming against their religion. I’m thinking I’m teaching a craft, a hyperbole—

RW: Yeah. [laughter]

IZ: —I’m teaching tall tales. There wasn’t room in that time or space to say, “Let’s pause for a moment.” What does that mean when your student tells you, “Well, I’m not God; I’m not going to write about that.” I didn’t have a moment to say, “Wait, let’s have a discussion.” The reality is they need an anthology at the end of the year, so you can talk all you want to about other conversations and discussions, but you’ve got to get some work done. I understand the very real practical things that have to happen, but this is a moment where I want you to have the opportunity to speak your truth and then say, “Hey, I never thought about that. What does everybody else think?”

RW: I think there’s a way to push for that though, and make time for it, even in a more traditional teaching artist residency. In the beginning, I was much more like, “Okay, this is what I’m supposed to do and this is the curriculum.” But the more I taught, the more confident I felt to say back to the organization or to the classroom teacher, “This is important. And your mission says… So, why don’t we figure out a way to really do it?” It is hard work and not easy. There’s some fumbling in there too, but I feel it’s worth trying. I feel process is important and not just product.

T&W: How has the teaching work you both have done influenced your own writing?

IZ: When I worked in high schools with teachers of writing, I was writing throughout, working on my novel while working in a high school near my home in Flatbush [Brooklyn]. I got to be up close and personal with those teens—how they moved, what they say to each other, the jokes…

RW: And you were watching two teens who clearly were in love and dating, on the train—

IZ: I was watching them on the train—

RW: She posted it on Facebook.

IZ: I took a picture of their feet. But I’m always watching young people. When I was in the classroom, I got to see the teen angst, the boredom. I remember my own teen-hood. The drama—or not—so it just puts me right there in the subject matter that I’m writing: how they respond to me, how I respond to them. At this point right now, when I write about teens their parents are my age! [laughter] I can’t write this as an old person. I think that’s why we have a different bird’s-eye view. We’re not going out to do the research and then writing the book; we’re writing from our experiences over the years with young people.

RW: And knowing what they’re capable of. I feel like so many times, the assumption is “That’s too serious,” or “They don’t care about that,” or “They’re not going to want…” No, I know teenagers who are serious about activism, like your daughters. I want to see those characters, those people—real people—represented in books. In that way, I also feel like a journalist. I have been in the trenches with young people across the board—wide ranges of communities and different class levels. I feel obligated to tell as many of their stories as I can. I want those young people that I have met to see their experiences in a book, too. Children’s books especially are usually the extreme stories that get a lot of hype and attention. There are so many stories that might not be the perfect, all-star, super-popular, drama-kid stories, but also not down-and-out, gangs, mama-didn’t-love-me, end-of-the-world stories. There are so many stories between that. Teaching taught me that, or reminded me of that.

IZ: It allows us to add nuance to our characters. I have to check my own propensity for stereotyping the “other,” because young people can still be the “other” even when I’m a parent. So, when I’m in their midst, it allows me to see them as fully realized human beings and to portray them in that way.

RW: When I’m in deep, after a few drafts, I start to think, what if an educator wants to use this book in the classroom. I hope that some of my work can be used to help conversations that we’ve talked about. So, I’m mindful of that too. I know that educators are super busy. There’s so much on a teacher’s plate. There’s testing, there’s a lot of pressure. I believe most teachers really do want to have these meaningful conversations, so how can my books be a catalyst for that? Having been in the schools and knowing a little bit of how they work, I want to be an ally with teachers.

IZ: The key is to include enough nuance in our stories for the teachers to be able to sink their teeth into.

RW: Right.

IZ: Just because we’re writing about a certain population, it can go either way. It can just be fluff and sensationalized material, or it can be something with depth. Something where there is enough context for whatever these kids are dealing with, for the teachers to say, “Let’s examine how this came to be.” If I go to a school visit, I say, “Let’s talk about redlining in these communities and what happens when people are disenfranchised and marginalized and placed into a box.” I want that to be in my book.

Part 2 of this interview will appear on February 20. In their continued conversation, Renée and Ibi speak about the creative act itself and how it affects and is affected by trauma, their recent book and teaching projects, and the impact of the 2016 Presidential election on their shared purpose as educators.

Teachers & Writers Magazine is published by Teachers & Writers Collaborative as a resource for teaching the art of writing to people of all ages. The online magazine presents a wide range of ideas and approaches, as well as lively explorations of T&W’s mission to celebrate the imagination and create greater equity in and through the literary arts.