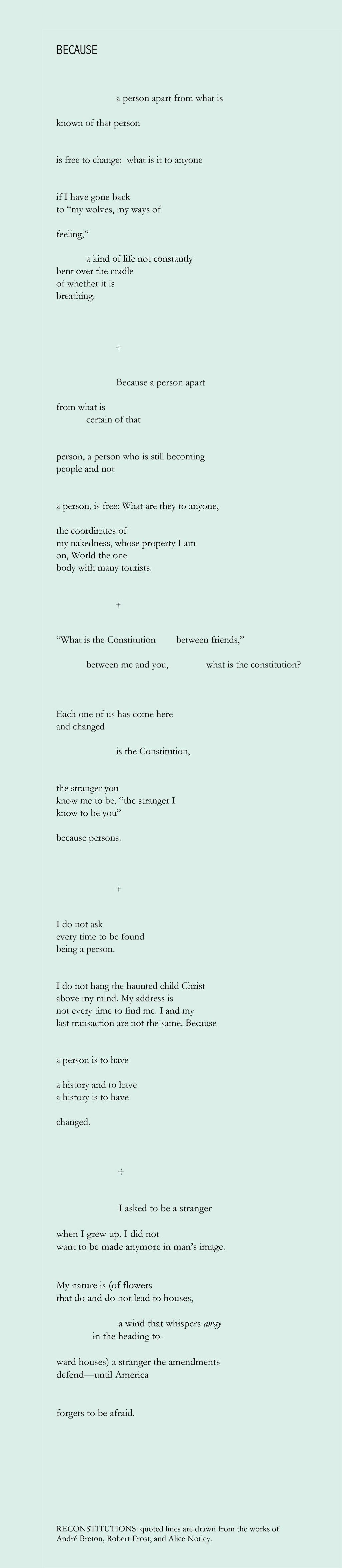

I began the poem “Because” after being asked to give a reading in support of Edward Snowden in fall 2014. I was in a cabin in the woods without Wifi at the time, and the invitation gave me an opportunity to reflect again on the “Nothing to Hide” argument regarding surveillance.

Now the first thing you’ll notice is that the poem doesn’t so much as mention Snowden or address any NSA privacy violations or search-and-seizure policy shifts per se.

Instead, the poem explores—more metaphysically—surveillance’s implications for freedom.

I realized that, for me at least, what is at stake with the potential for accumulated facts and retrospective data about me/you/us is our freedom to change. If we are increasingly identified by virtue of which sites we’ve explored, which products we’ve purchased, which people we’ve befriended and affiliations we’ve formed, which questions we’ve asked en route to becoming and changing—en route to creating the Stranger we are and have the right repeatedly to be—then we are potentially not free.

I began to think of freedom as being synonymous with the freedom to change, with the capacity to re-constitute one’s self or selves. And this poem was a way of heading toward and testing that hypothesis.

When I consider “activism,” I think of something that is constantly re-constituting itself and renewing the nature of its activity.

In a recent NPR piece called “Where Have All the Poets Gone?” Juan Vidal laments the lack of activism in contemporary poetry and suggests that Allen Ginsberg, Amiri Baraka, and Pablo Neruda were the last great members of a more engaged generation.

To which I would say the following:

In poetry, we don’t abandon the works of past thinkers and provocateurs: Neruda, Ginsberg, Baraka are not old products and brands that we quickly remove from the shelves of our consciousness. They are authors whose works and ideas continue to provoke and instigate in our time. That’s why we have the permanent present tense when we discuss books and literature. And that’s why we have the humanities, which are not based on a temporary banner or headline (at least, for now) but on a continuum of ideas and questions.

But to say that poets are not political because they don’t make headlines anymore or take to the picket lines (which I personally have done at least ten times in the past fifteen years, and I am less active by far than other poets) is to suggest that poets should, in some ways, conform only to the specific structures of attention-getting that our society condones and recognizes and that our media “covers.” Covers takes on a new meaning here, like a lid.

In addition to several overt examples of activist (and politically activating) poetry collections and compendiums—among them, M NourbeSe Philips’ Zong, Juliana Spahr’s This Connection of Everyone With Lungs, Claudia Rankine’s Citizen: An American Lyric, Anne Waldman’s The Iovis Trilogy and Civil Disobediences, Thomas Sayers Ellis’ Skin, Inc.: Identity Repair Poems, Frank Smith’s Guantanamo (trans. Vanessa Place), CD Wright’s One with Others, Fred Moten’s “The University and the Undercommons,” Gabriel Gudding’s forthcoming Rivers for Animals, poet-journalist Eliza Griswold’s I Am the Beggar of the World: Landays from Contemporary Afghanistan, Cecilia Vicuña’s A Menstrual Quipu: The Blood of the Glaciers Journal, and countless other examples—there is a subtle, perhaps less noticeable shape our activism is taking.

We as poets are using our structural imaginations to create innovative amalgams of international sharing, like Ubuweb and Penn Sound. We are reshaping statistical dialogues through VIDA: Women in Literary Arts and reimagining continental colloquy through TrafikaEurope, which has launched Europe’s “first online literary radio station.” Upcoming issues of TrafikaEurope reconceive of Europe through the lens of the Roma people as the largest EU minority and (in another future issue) focus not on the United Kingdom but on “Europe’s northern islands,” compelling its readership to consider resonances between Scotland, Iceland, and Svalbard, instead of confining their ideas of literature to nationalist or linguistic boundaries. We are creating dynamic translation laboratories like Peter Waterhouse’s Versatorium in Vienna, in which poetry translators use ingenious, heretofore unimagined means to assist and support asylum seekers in Eastern Europe and revive the collective identity and creative lives of rural communities suffering economic blight. We are building arts collectives such as the Chilean group Casagrande, which has staged bold and compelling pacifist actions. Casagrande’s “The Rain of Poems” featured massive “poetry bombings” from helicopters over cities like London, Guernica, Warsaw, Berlin that have suffered air-raids and fire-bombings in their war-torn pasts: combining poems by poets in those respective countries with Spanish poems/translations, Casagrande has created, according to journalist Zelijka Lovrencic, “a thread binding all citizens” and fostered new ways to awaken conversation and presence in an otherwise “alienating society.” And, we were and are instrumental in the Occupy movement and in continuing its multi-vocal and contributory momentum. As Aaron Gell claimed in the New York Observer, “If you really want to understand Occupy Wall Street, you have to talk to the poets.”

Vidal’s article seems nostalgic for a time that actually had many different opinions itself about what constituted the political. I was struck by Ralph Ellison’s 1953 comments in some recently discovered sound recordings in which he says the following bold (and implicitly political) statement: “It’s a terrifically difficult thing this business of trying to decide what is real, what is valuable […]” and to ask a writer “to go out on the picket line, […] is all right by me, but it isn’t writing and I don’t think the two functions should be confused. I think that there is enough pain, there is enough psychological misery involved in really grappling with reality in terms of Art….”

In meditating on contemporary poetry, I’m tempted to connect this “grappling” to Stanley Cavell’s insights in The Senses of Walden (Viking Press, 1972), in which he suggests that every action that Thoreau describes (whether it be building the hut, greeting a stranger, planting beans, grappling with solitude) is a part of the comprehensive and multifaceted verb: to write. Cavell argues that we as a culture have narrowed down our perception of that verb to a singular, static, desk-bound action, whereas it is in fact a vital nexus of activities. Or, one might say, Activism.

Christina Davis is the author of An Ethic (Nightboat Books, 2013) and Forth A Raven (Alice James Books, 2006). Her poems and essays have appeared in the American Poetry Review, At Length, Boston Review, The Concord Saunterer: A Journal of Thoreau Studies, The Occupy Wall Street Poetry Anthology, Poetry Magazine, and other publications. She worked for Teachers & Writers from 2001–2005 and currently serves as curator of the Woodberry Poetry Room, Harvard University. She wishes to dedicate her poem to Steve Shapiro and Nancy Larson Shapiro.