We weren’t allowed to have snacks in the classroom, and this was a problem. I teach MFA students in the Creative Writing Program at The New School, where courses meet in the evening. Up until the pandemic hit, I brought food to class, bags of shrimp chips or sleeves of Oreos, to help us transition to writer-mode and to provide energy for the two-and-a-half-hour session. But in the fall of 2021, when we moved off Zoom and back into the classroom, masks were required, and food forbidden. Enter, crayons!

I love opening a fresh box of Crayola crayons, the wax vibrant against the matte paper wrappers, the tips of the crayons perfectly crisp, begging to be used, or maybe even eaten, good visual stand-ins for snacks. What I didn’t anticipate at the beginning of the semester was that bringing crayons to my novel-writing workshop would play such an important role in how the class developed, the low-stakes drawing exercises we did helping to reduce anxiety and create community.

What I didn’t anticipate at the beginning of the semester was that bringing crayons to my novel-writing workshop would play such an important role in how the class developed . . .

As I experimented with incorporating drawing into my writing class, I adapted three exercises from Syllabus, Lynda Barry’s book on teaching cartooning: a simple coloring exercise, a drawing-with-your-eyes-closed exercise, and an exercise in collaborative cartooning.

For the first class, I asked the students to color in one sheet of 8.5 x 11 paper as dark as possible, trying to eliminate any white space. We colored for a few minutes, and then I told the class to continue to fill in their pages during any free time they had throughout the class session, that we’d check in on our progress during the last few minutes of class. We then moved on to the other first-class activities I’d planned. Throughout the session, students intermittently continued to darken their pages.

When we looked at the papers at the end of the session, it struck me that no one had done the exercise in the same way. The students had all chosen different colors, for one thing. Some of them used more than one color. The patterns of their markings varied. Some students drew horizontal lines, others made diagonal marks or swirls. One student had taken the paper off a crayon and used the side to color the paper, resulting in a transformed page, waxy and thick. As a class, we talked about these differences. Even though there was no one right way to do the exercise, several of the students denigrated their own work, even as they were enthusiastic about what their classmates had done.

The results of the exercise were not where I saw its value. What I try to teach in the novel class is that “good” and “bad” are unhelpful binaries, especially in the context of novel-writing, which is more than anything, a long process, as difficult as it is rewarding. So it’s a process that I focus on, helping students develop stamina and flexibility. Over the course of the semester, I noticed that by keeping their hands occupied on the straightforward task of coloring, the mood of the room lightened, even as we worked on the writing exercises, enabling us to engage in what Robert Frost called “serious play.” By the last class, we were all used to drawing in class, and it felt natural to attempt a more complicated and time-consuming collaborative cartooning exercise.

To warm up, we started with Barry’s drawing-with-your-eyes-closed exercise. You can try this yourself. Set a timer for a minute. Draw one thing for the duration: a shark; a bacon and egg breakfast with coffee, toast, and silverware; a zebra with stripes; a car; a helicopter; the Statue of Liberty. I’ve now done this exercise with students of all ages, and it’s interesting that one of the first responses from practically everyone is, “I can’t do that!” When people look at their drawings, they sometimes get the hysterical giggles. They say, “That’s terrible!” But the drawings never are terrible. The objects are recognizable, the parts connected to each other in an oddly elegant way, humming with life.

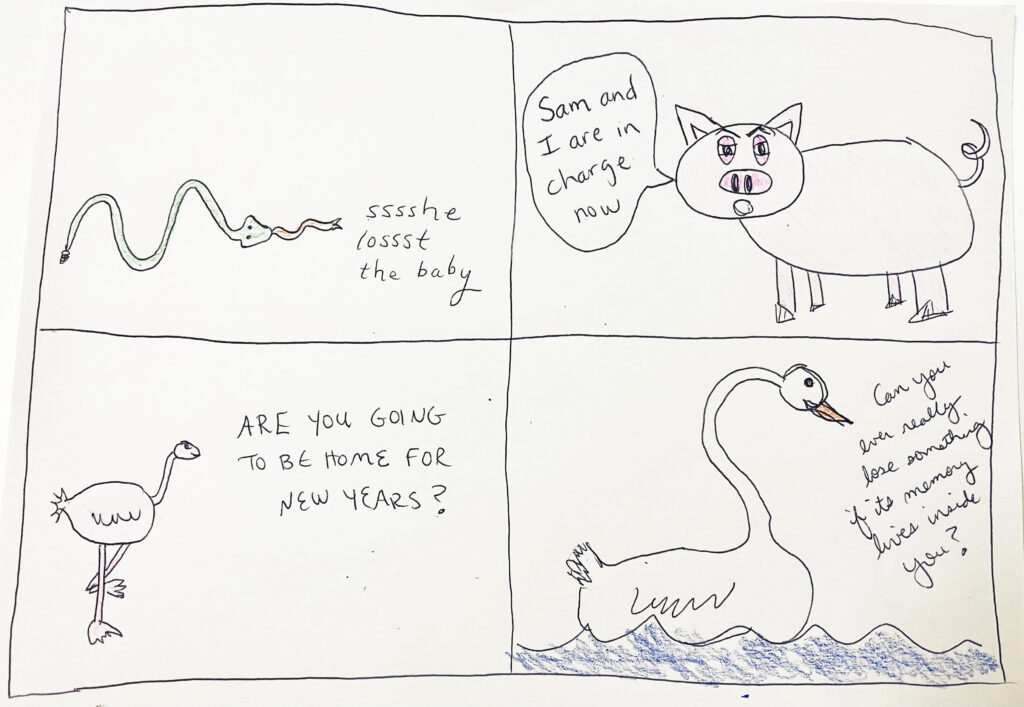

The steps for the collaborative cartoon exercise are relatively simple. Begin by distributing blank sheets of paper to each student, and then lead the class through the following instructions:

- Orient a piece of paper in the horizontal position.

- Draw four frames.

- In each frame draw a different animal, fish, insect, etc. [Alternatively, draw the same creature/animal/person, each one looking in a different direction.]

- Pass these drawings to the person on your right.

- On a new sheet of paper, write the numbers 1-4, leaving space after each number for a short answer.

- The instructor gives the following four prompts (these are suggestions—the point is to have prompts that produce short pieces of text):

- Write down something you recently overheard.

- Write down some song lyrics.

- Write a question you’ve been thinking about, but use language like you are writing in your teenage journal.

- Write an imperative sentence, i.e. someone giving someone else an order.

- Pass the answer sheet to the right after each answer so that the completed sheets have responses from four different people.

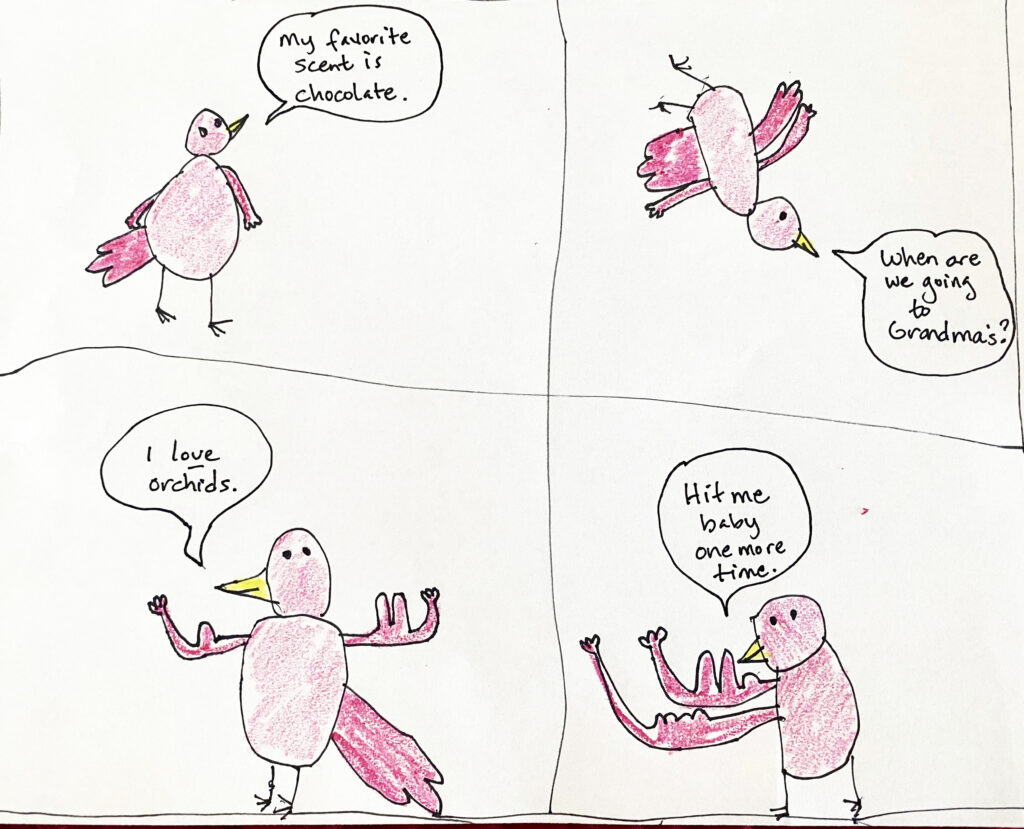

- You’ll now have one answer sheet and one piece of paper with the drawings you received earlier from the person on your left. Take the answers and decide which frame you want to put them in, writing the text in either a speech or a thinking bubble.

- Pass the comics to your right. On the sheet that you receive, add color to the characters and the background. Add the ground or sky, coloring in the background as much as you’d like.

- You now have a four-panel collaborative cartoon. Show and tell.

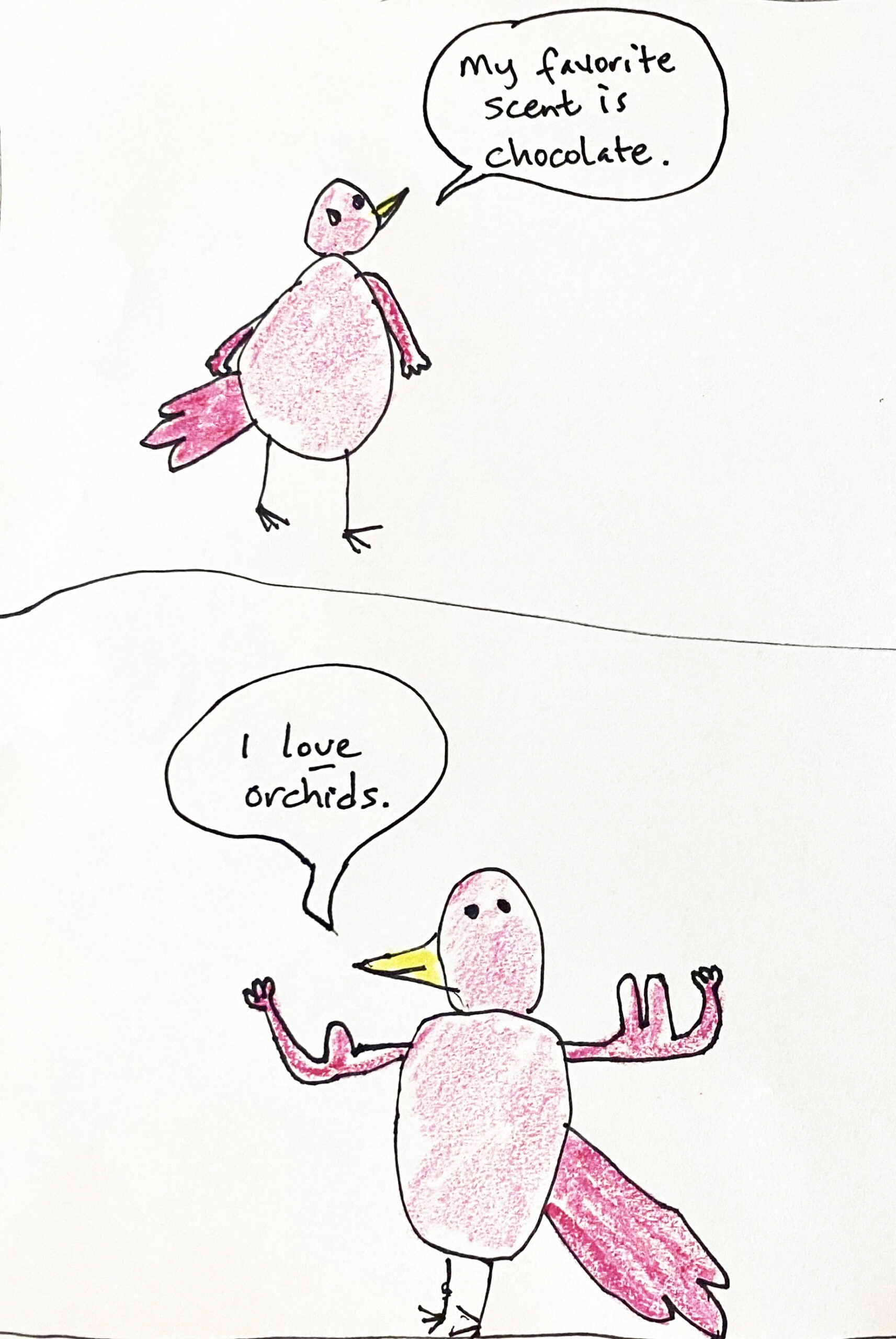

When I did this exercise with my graduate class, I wasn’t surprised that there was an initial bit of resistance, mostly manifesting itself in the usual: students wanting to do a good job. But one of the valuable lessons of this exercise is that the cartoons are a lot funnier and the end result more magical when the drawings aren’t technically great.

Curious to see how the exercise would work with different groups, I attempted the cartooning exercises with my nieces and nephews in California and North Carolina. Their ages ranged from seven to 13, and I assumed that younger kids wouldn’t have the same inhibitions about drawing exhibited by my graduate students. I couldn’t have been more wrong. The kids also wanted to do “good” drawings. And competition entered into the process in an interesting way. For the adults, collaboration seem to allow them to appreciate how their work meshed with the work of others; for younger kids, collaboration threatened their autonomy, oftentimes making them feel like they were being forced to share, a wretched feeling for a kid. Not that I’m saying that kids can’t do these exercises. With all groups, I learned that there’s some handholding required during the initial steps, reassurances given when participants exhibit frustration, annoyance, and dismay. The reward comes during show and tell, everyone is laughing, amazed that working together and being silly could produce such delightfully bizarre and moving results.

The feeling of “I can’t,” or “I won’t,” or “I don’t want to,” come up often when I write, but because I’ve been doing it long enough, I know that if I stick with it for an hour—or a day or a week—I’ll get to the good stuff. The writing exercises I give are intended to allow students to trick themselves, to make it easier for the unexpected to appear. One of the nice things about working on drawing together is that we see, in the work of others and in our own, the mistakes, the oddities, and the flashes of pure energy that wriggle through our defenses.

This is why I write, to be surprised and challenged, to chase away the stale and the dead. Drawing with my writing students helped me relearn the thing I’ve learned and forgotten too many times to count: that the only way to the good stuff is to keep my hands moving.

Luis Jaramillo is the author of The Doctor's Wife, winner of the Dzanc Books Short Story Contest, an Oprah Book of the Week, and one of NPR's Best Books of 2012. His novel The Witches of El Paso is forthcoming from Atria Books in the fall of 2024. He is an Assistant Professor of Writing at The New School and is the Chair of the Board of Directors of Teachers & Writers Collaborative.