Editors note: This article was originally published in Teachers & Writers Magazine 1997.

Can adolescents learn anything profound about the intricate and powerful relationship between language and war? In a century haunted by phrases such as “acceptable losses” and “mutually assured destruction,” can we as teachers help guide our students to some kind of understanding about violent conflict?

Can we help our students make decisions about the Gulf War or the conflict in Bosnia, which many of them have experienced via television? How did they deal with terms like “carpet bombing,” “softening troops,” and “collateral damage,” which were pumped into their homes on a daily basis during the invasion of Iraq? And how can they intelligently enter any future national debate over what “supporting the troops” really means?

The relationship between war and language has become even more crucial than it was in the past. In our century, war can be waged on a massive and thoroughly inhuman scale; we now have weapons of “tele-destruction,” weapons that can maim, kill, or obliterate—and all at a safe distance, where the smell of blood and the sight of corpses can’t penetrate. In addition, advances in media technology, as well as in the psychology of persuasion and information control, have made the physical reality of war even more distant than our ancestors’ romanticized ballads and idealized woodblock prints did.

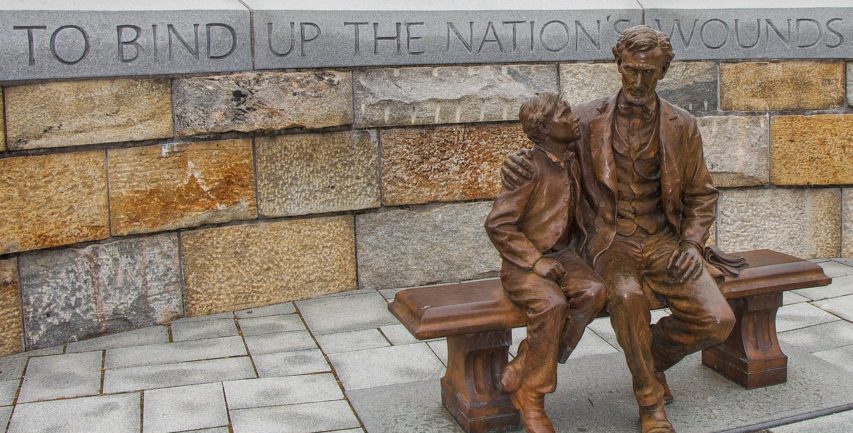

And then there’s the age-old tendency simply to turn away from awful truth, or to rationalize it. A recent article in Civilization magazine reminds us that 26,134 men died on one day at Antietam in the Civil War—almost half as many Americans as died during the entire Vietnam War. The Confederates and the Union each “lost” roughly the same number of soldiers—but General McClellan of the North, in Michael Kernan’s words, “declared it a glorious victory.”

I’ve developed a unit for English class that addresses this crucial topic—a unit in which almost all of my students, from year to year, have worked with dedication and energy. The results regularly included some of the best writing that I ever received, both from high-achieving students and from those with less apparent ability and interest.

“Was [the war] worth it?” a high-school junior and cheerleader wrote. “Was the cost of the war worth the end result? According to the people…it was not. Many died on all sides and homes were broken up… It…seems sometimes countries start wars just for a powerful feeling anyway. Nobody wants to get hurt and everyone expects to win. Although, we all know the truth….” Another junior—a very poor writer overall—created a scene in which a child watches her older brothers march off to war: “…they were so loving and playful when we were together. It was hard for me to believe that we may never see each other again. Their bodies looked so stiff in their uniforms, and their faces looked so pale and sorrowful….” A third, whose written work was otherwise unremarkable and whose interest in English was marginal, handed me an envelope stuffed with photos, medals, a locket, and the half-burned diary of her character, a doctor, whose first experience of war brought up deep fears: “This war promises to be…bloody…and worst of all, my brother Michael is in it. I fear for his life and that one day I will see his face on my operating table.” The envelope was in fact the personal effects of the doctor whose family, reading the diary, was just learning of his death.

My “War and Language” unit takes three weeks to finish and consists of two main parts. During the first, students read a variety of written material about war. During the second, each student assumes a character—soldier, doctor, spouse of soldier, etc.—and writes about that character’s experience in a mock war we hold in class. By pretending to be real people experiencing a real war, students can begin to consider how words and attitudes influence each other; how, for example, both our Vietnamese enemies and allies were called “gooks,” and how friend-or-foe decisions might have been colored by that word; or how, as Russell Baker has said, “megadeath” doesn’t have quite the ring of “a million corpses.”

Before either section can begin, I teach the necessary vocabulary. Even eighth-graders are perfectly capable of grasping terms like “euphemism,” “abstract,” “concrete,” “distancing,” “metaphor,” “jargon,” “technical language,” “dehumanize,” and “doublethink.” Students will master vocabulary if the teacher presents only five to ten items a week, explains them clearly, gives many examples, and has students use the words repeatedly. I also introduce the key idea: Language can distance us from the reality of war, or bring us closer to that reality. For example, the Russians leave “turbulence” behind them as they withdraw from Afghanistan; an article mentions the “effectiveness…of non-ofnuclear bombing.” The concrete referents of these words—what it feels like to be bombed or machine-gunned, or to step on a land mine, or to be orphaned or widowed by the violence of war—are lost in the vagueness of such language. As a class, we come back to this fact again and again.

Then, for a week, I have the students read material on war and fill out “Read and Respond Sheets.” I present a large collection of writings about war; students must choose a certain number of these pieces and fill out one sheet for each. The sheet asks two questions: What was the attitude toward war in this piece of writing? and, What key phrases show this attitude?

The kind of writing about war that I make available to the students is important. For one thing, I include pieces that reflect every possible level of reading ability. And of course, these writings must hold the students’ interest. There’s wild variety in my collection—a passage from the Iliad, a section from a history book, a G.I. Joe toy soldier pamphlet, a Mad magazine satire on weapons sales, Sgt. Rock comic books, articles on nuclear war, letters (some from soldiers in Vietnam), encyclopedia articles on weaponry, etc. I can also require each student to read a book on war, anything from Slaughterhouse Five to Dear America to The Naked and the Dead (depending, of course, on readability and the students’ reading levels).

This variety allows me to direct individuals to material that will engage them. I can include “heavier,” more demanding writing for students whose interests and abilities move in that direction. Pieces on the Gulf War or other recent and therefore more familiar conflicts can be incorporated into the lesson—or purposely left out, since heated disagreements could disrupt the learning process.

These readings also provide details about actual war experience, details that inevitably show up again in the students’ own stories.

Again, we focus as a class on the human tendency to talk away from the realities of war. What does it mean to say that the improved U.S. military is “tougher”? What exactly are “atrocities,” in plain English? What underlying attitudes cause an unnamed source to call U.S.-Soviet satellite conflicts “the ultimate video game”? Why did the term “Star Wars” become so popular a misnomer for SDI? Do teenagers fully analyze the meaning of “Be all that you can be”? Can the word “war” itself, or any other words, really capture in any immediate sense the overwhelming reality of combat?

I also ask students to do an adult interview for one of the required sheets, focusing on “the cost of war.” This means that they apply our two basic questions to a discussion about war that they hold with someone over thirty years old. I ask the students to begin with the question, “What, in your experience, is the cost of war?” and then to analyze their notes on the discussion for “attitude toward war” and “key phrases.” Films, photographs, and recordings, if available, can also count as resources revealing attitudes toward war. This almost automatically means that my kids experience actual and fictional war stories—in many cases coming to school amazed at what they’ve heard from their parents, relatives, or neighbors.

Once I feel my students have some background, I bring out the maps. These maps represent three countries in the imaginary world in which our mock war occurs. Using felt-tip markers and colored pencils, I created two maps, each poster-board size, then laminated them. One is an overview of my made-up world and the other an inset that enlarges the area where most of our imaginary fighting takes place. (The map of some real-world theater of war could be substituted here—for example, World War II Europe or contemporary Bosnia—if the teacher feels she can keep the discussion objective enough and wants to include actual historical events in the unit. This could also work well for team-teaching with a history or social studies teacher).

Showing these maps to the class for the first time is a motivational high point in the unit; it’s crucial in getting the students involved in the creative writing that lies ahead of them. Nothing in the unit seems to attract my kids so much as the sight of these maps, the richness of an entire world in which to let their imaginations play.

The maps must be detailed and visually attractive. They include seas and continents, nations, cities, villages, rivers, mountain ranges and other features, all of which are named. This, of course, is a familiar feature in adventure and fantasy books, and has proven over time its attractiveness to adolescents—and to adults.

In this imaginary world, as I explain to the students, two of the nations are fighting over a border province with newly discovered mineral wealth. In this province, the two cultures have intermarried to some degree. Hill tribes live in one of the embattled areas. Both of the large nations have particular claims to the province. As tensions mount, an assassination by young hotheads and a massive reprisal from the other side provide the pretext for war. In effect, I give my students a vast story—a history—from which their own stories can naturally flow.

Once my class has some basic information on the state of things, I pass out character lists and hold a “character auction.” The characters on the list reflect many different perspectives on war: soldiers, generals, prime ministers, parents or relatives of soldiers, tribespeople, journalists, children in the war zone, spouses from mixed marriages, military press-release writers, community leaders, doctors or nurses, business leaders, religious leaders, ordinary citizens—even an extraterrestrial observing human behavior from the air and a historian writing fifty years later. Students “bid” by announcing which characters they’d like to be; disputes are settled by the “rock, scissors, paper” method, itself an exercise in conflict resolution. I see it as a small but significant learning experience—a tiny glimpse into the actual meaning of the word “diplomacy.”

I ask the students to think hard about their characters before they write, and then to use the kind of language about war that their particular characters would naturally use. How does a soldier’s mother or father react to the abstract word “casualty”? What do “tactics” mean to a military thinker—and to a surgeon in an army hospital? American teenagers probably won’t feel quite the same about Conan the Barbarian after they’ve imagined themselves as tribespeople whose world is being destroyed in a clash between larger powers.

Then the mock war begins. I tape the maps to the chalkboard and use magnetized colored disks to represent battalions (these disks are about an inch or so in diameter and will affix to chalkboards with metal backs). Then I set up simple campaigns on the map, since I control the movement of troops. When armies meet, a “battle” ensues (this happens each day for four or five days). The outcome of the battle depends on the roll of a single die (which we refer to half-jokingly as “Fate” and which the students love to roll themselves, one representative from either side).

The overall assignment is for each student to write about his or her character’s experiences during the first four or five days of the war. I encourage them to write in different forms: diaries, letters, memos, novel excerpts, sermons, requests for supplies, etc. We emphasize the range of language they produce—from the most specific to the most euphemistic or abstract—and how such half-conscious language decisions influence individual attitudes toward the war. But I give them a lot of freedom in their writing. As long as they follow the basic background and troop movements, they can make up anything they want. (I don’t want to inhibit their creativity, for example, by insisting that their stories somehow all fit together.)

During this phase I circulate, reading, coaching, and inspiring if I can. I point out examples of insight or strong writing, ask about grammar or clarity, remind them to fit their language to their characters. I talk about characterization and dialogue. I model the creative process by telling anecdotes, by suggesting conflicts, themes and plots, and by helping students see where the natural drama of their characters’ experience lies. I question wording or events, bolster certain ideas with praise or further suggestions, lay out options for mood, voice, and pace. Even more exciting for me is to see my students spontaneously telling each other their stories. Many of them do this with passion and gusto, developing their stories and making changes appropriately—a perfect pre-writing activity. Students also act spontaneously as each others’ critics; around the room you’ll hear “There’s no way he could do that.” “Cool!” “But how many days would it take to get there?” “Why should the soldier care—he doesn’t even know them!” Immediate responses like these greatly strengthen the eventual form of the stories.

By the end of the five days, each of the students has an excellent rough draft. We then talk about turning rough material into a finished piece, through selection, compression, summary, polishing, and the like. Their final drafts are often very good; many of their stories are compelling and richly realized. I use these compositions as the basis for their grade for the unit.

One of my students—a classic underachieving gifted male—developed an elaborate and profound espionage plot in which the reader of his document learns that, while reading, he too has been contaminated with poison soaked into the paper, just one more victim in a chain of murder. Another’s story ended with a mother learning from casual conversation that her son had died in battle—her grief erupting when strangers happen to mention a unique scar on the face of a nameless corpse. The first student was a high school junior, the second an eighth-grader.

Four other factors will affect this unit.

A teacher who is well read in war literature, and especially one able to relate anecdotes about war, will engage the students’ attention and motivate them much better than a teacher who can provide no examples of what really happens. Paul Fussell’s book The Great War and Modern Memory is a perfect resource, and is a masterpiece of its kind besides. He writes, for example, of Wilfred Owen’s artistic struggle toward concrete language—how Owen writes his mother about the “sufferings” of his men but changes his tone in a letter to Sassoon, another soldier-poet: “The boy by my side, shot through the head, lay on top of me, soaking my shoulder, for half an hour.” George Orwell’s seminal essay “Politics and the English Language” is another valuable resource, and one that discusses the connections between language and behavior in general. Some familiarity with works like these will provide a teacher with well-chosen examples that can have a powerful effect on students.

A teacher must also maintain his or her own political objectivity when presenting a topic like this. Students often hold varied opinions about war; from the beginning of the unit I emphasize that I won’t try to convince anyone that war is wrong or right, but that everyone should have some sense of the reality of war, of what really happens, through direct language. Some students may object that this approach in itself is “liberal” or “anti-war.” My response is that I, as a teacher, can ask certain questions, but that the answers to those questions can only come from individual students. I support this idea by showing respect for all the heartfelt reactions my students present.

I also spend some time talking about the natural human tendency to become desensitized to violence, and I insist my students realize that even the most direct language can’t capture the actual experience of combat.

Finally, to ensure that my students write about the human experience of war—instead of distancing themselves from it by treating it as a game—I let them know from the beginning that we’ll write only about the first days of the war, and that none of us will ever know who “wins” the conflict. Playing a game of Risk is hardly the way to encourage accurate language about war; at this point, too, we discuss exactly what it means to “win.”

I always end the unit by discussing the ways in which language is being used and misused in the greatest human crisis of all time—the nuclear age. When an American president can refer to the Soviets and their political philosophy as “cancer,” “virus,” and “the focus of evil in the modern world,” I expect my students to identify the dehumanization that such language encourages. We talk about phrases like “nuclear deterrence,” examining the huge conceptual gap between the cloudiness of the words and the real possibility of massive human suffering much worse than that at Hiroshima.

My hope is that this unit can help my students, as participants in the ongoing human struggle concerning war, to begin to see the essential role that our awareness of language may play in its resolution.

Tim Myers is a writer, songwriter, storyteller, and university senior lecturer in English. He currently teaches education writing courses at Santa Clara University, California.