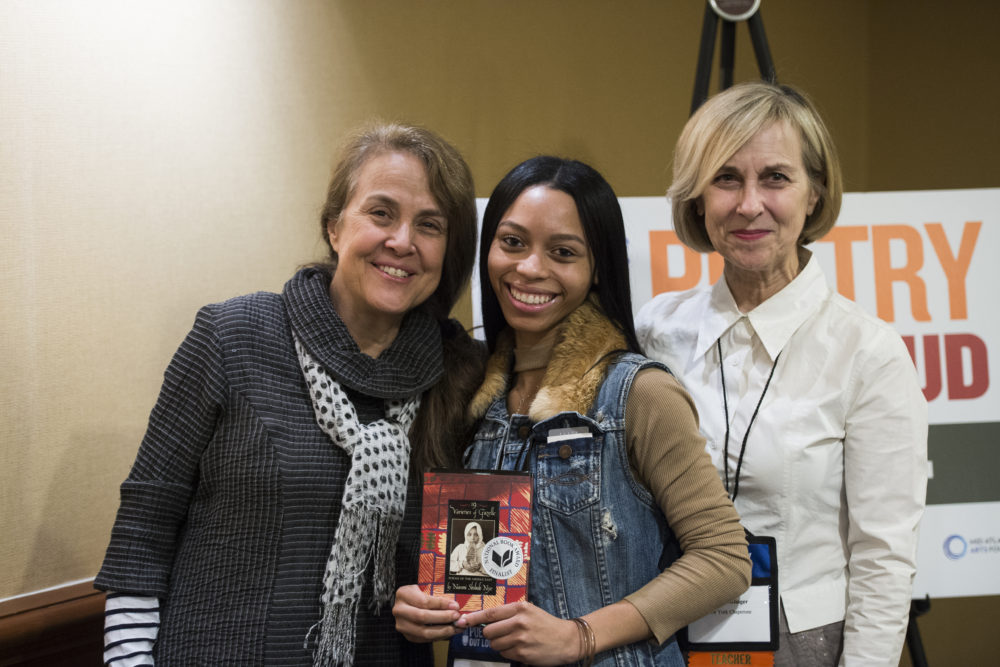

Lydia Esslinger says that she has been an English teacher and speech and debate coach at Syosset High School on Long Island “forever.” Eight years ago, she learned about Poetry Out Loud and brought the program to her school. One of her students, Iree Mann, is the 2017 New York State Poetry Out Loud Champion and finished third in the country at the national competition. In this conversation with poet, playwright, and T&W teaching artist Dave Johnson, Lydia talks about how Poetry Out Loud benefits both students and their teachers.

Teachers & Writers: How long have you been involved with Poetry Out Loud, and why did you get started?

Lydia Esslinger: I’ve been involved for about eight years. I think I saw something online about it. It was terrific when I saw it because it combined two things that I really liked, which were poetry and the spoken word.

T&W: Have you done Poetry Out Loud every year for eight years?

LE: Oh, yes. Once I found it, I said, this is a definite.

T&W: Can you tell us a little bit about how it works at your school?

LE: Sure. I think poetry is the neglected genre in high school, or at least in my high school it is. Which is not to say that people don’t do any poetry, but it isn’t featured. It’s an ancillary thing. You’re reading some fiction, and here’s a little poem that might go with it. Because that’s the case, I send things out to all of my colleagues mentioning POL, saying that this is available, and that I would have a little meeting after school on a selected day. I say we’re looking for people who would be interested in this magnificent opportunity to make beautiful things or fascinating things heard aloud. And to win some money, of course. That’s a big draw. I have a meeting with students. I play some videos [from the national POL website] because that’s the best way for them to see kids their own age doing what I hope they think they can do. So it starts in classrooms, and then we have an in-school run-off.

T&W: How do you help students to prepare for the program?

LE: I spend a lot of time with them. I ask them first to go home and actually troll through—and it’s a lot—the [Poetry Out Loud] anthology. I say, please find poems that you like. Sometimes they come back right away, say in two or three days, and have the poems. And I say, that’s great. Keep them in your back pocket, but I want you to shop more. For me, the big thing about this is loving this art form, and I think the way to get that is by exposing yourself to as much of it as you can. I give them a lot of time to look, and when they think they’ve found something, I encourage them to look even further. With the idea that what you found first, if it’s the one you want most, it will make itself felt.

T&W: You said earlier that you used video with the students that are interested in the process or getting involved. Can you say a little more about that?

LE: I think students like seeing people their own age, or at least they understand people their own age, doing something. For me, what’s worked best with them is seeing somebody do it. So that’s it. We’ve played a lot of them. They’re entertaining. It’s a good way to keep kids interested. I play males, females. People who seem younger. Funny poems. It’s like watching a little movie, you know. It’s fun for them. And of course, they pass judgment on everybody. They have their favorites, and that’s understandable. Oh, I really liked her. Or she was too fast. Or he has such a nice smile. She dressed well. [laughter]

For me, the big thing about this is loving this art form, and I think the way to get that is by exposing yourself to as much of it as you can.

T&W: That shows that it’s engaging them. That’s great.

LE: And what I like even better is they say, wow—that’s a really good poem. Or I really like that or I didn’t understand that one. But that’s okay. They need to talk about it.

T&W: What would you say to a teacher who asked you if they should they get involved in Poetry Out Loud?

LE: Oh, yes! Well, I think the teacher needs to have some affection for this. I’d say it’s a wonderful thing to introduce into your curriculum, into your classroom. But sometimes I think it’s a little hard to navigate the anthology. What I mean by that is you don’t know where to start. I’m speaking about kids, but also me. And a lot of those names are familiar to me. But if you don’t know what you’re looking for as a student and you are looking through that thing… The way I’ve found best is to pop the pictures on and start with that. So people put a face and a name. So kids can say, I’m looking for a female…

T&W: You mean the pictures of the poets?

LE: Exactly. Starting with the pictures, rather than the alphabetized poems.

T&W: So that is still a little bit of tough part. Exactly how to find the poems.

LE: I think so, because God knows there are so many there. And I think it’s a great anthology, by the way. There’s so much there to choose from. Honestly, I have sat down sometimes after the kids leave and we’ve had a little practice session, or even before when they were looking for poems. I just sit in my office, and maybe this is crazy of me, but I could be there for two hours looking at the anthology. It’s fun for me.

I think that’s another thing I would say to teachers. I know we’re so busy. We have so many papers to grade, that sort of thing. But I find it a treat. You can just live in words for a while and not have to worry about doing anything with them. They’re just there, percolating for you. And then you can bring them into your classroom and say, look what I came across yesterday. Isn’t this great? And the great thing about poetry, as you know, is because it’s brief, you can make time for it in a particular class. I have friends who, and I’ve done this too, start the class with a poem a day. A short one. And kids have a little response notebook, and they write a quick reaction to it. So if nothing else, it exposes them to something they don’t take time for themselves.

That’s another thing I would say to teachers. I find it a treat. You can just live in words for a while and not have to worry about doing anything with them.

T&W: That’s beautiful. I love how you said “live in words for a while.”

How did you prepare Iree to go on to regionals, and then the state, and then eventually the national level?

LE: I spent a lot of time with her. As I said, I like this anyway, so I think it was really very collaborative. She found the Rita Dove poem [“American Smooth”] very quickly. She found the Rita Dove quickly, and I said, that’s great, let’s hold it. And then we looked for other things.

The second poem she did, the Terrance Hayes poem [“The Golden Shovel”]… In that case, she didn’t come up with that. I ran across it. I told you I sat and I read a lot of poems. I was looking for things that I liked, but also that I thought spoke to her cultural references. She resisted that poem and said, I don’t know what it’s about. And I said, that’s okay. Things take a while to reveal themselves. I said, I don’t know about you, but I think it’s really powerful. I said, just look at it a little bit more and see how you feel. She did that, and then she said, now I’m getting it. Which is great, when things kind of dawn on you. So way before she memorized it, we talked about it a lot. You know, it’s a lot of Q and A. What’s going on here? What parts do you like? What are you confused by? So it was pretty much a tutorial on close reading. I think we spent more time, honestly, on not the speaking part—that came—but living with the lines.

This happened with all three poems, including the third poem she picked [“Break of Day”]. And that was a deliberate choice to try to find something lighter. Kids often have a hard time with the pre-1900 poem. It’s not the language that they’re used to often, so it’s harder to look for. I’m a John Donne fan. I think you don’t get much better than him back in the day. I found that one for her. But she came with a whole bunch of her own, and this happens with all my students. They bring some older poems and some modern poems. They say here’s a poem I really like or I love it. I love it. And of course, those are the ones you pay the most attention to. But there’s a lot of talking about stuff, and crying over lines. In the case of Iree and me, I think we were both moved by things that we read and just kind of let it go. It was really living through the language. It was really a wonderful experience for me to see somebody who I think had very little exposure to poetry kind of become awakened by that and love it. I think this was really new for her.

T&W: How did you feel when Iree won the state and then went on to nationals and did so well? Can you say something about how you felt in those moments?

LE: It felt great! It really did. I’ve often said this about students of mine in the speech and debate world. What I like best is when they reach a level where there’s a larger audience. And I try to tell them that it’s not about the winning. Of course, the winning is nice. But it’s about a moment to give something to someone, something that you like. To have people hear it. You’re a vessel for this sentiment, and you can see it as a kind of sharing. People have got you and it for that little bit of time. And that’s great. The rest is completely out of your hands. So seeing her on the stage and in it, as she was, I felt wonderful. For different reasons with the three poems, too. I just wanted people to hear them the way I think she heard them. It was a great feeling, and of course for her, too. I think she felt good doing them.

T&W: What would you say is the best part about POL?

LE: I said the sharing thing, and I do mean that. It is out of your hands at some point. But the notion of a competition means that you can’t slack off. Once you put something in a competitive mode, you can’t kind of rest on your laurels or not give it all. There’s something riding on it. So that’s a motivator, I think. That’s a reason to go all out.

But I like a lot of it. I like the preparation of it. I like the process of it. I like looking for the poems, almost starting from scratch and saying, okay, we’ve got all these things here. Where do we start? What are kids liking when they come in the initial stages? What are they gravitating toward? Often they want Robert Frost right away because that’s who they know. They don’t know there are other poets out there. I like the different stages of POL for different reasons.

T&W: It’s really interesting that you found a balance between the competition and the idea of sharing. How did you arrive there?

LE: I think a lot of that comes from my having done the speech and debate stuff for so long. I always tell my students that one of the things you will learn from this is that you lose. There are subjective judgments here. It happens in classrooms, too. Maybe not in all subjects, but in something like English, you wrote an essay and you think you did something wonderful, and the teacher says not so much. But when there are other people doing the same kind of things you’re doing, at least in the same ballpark, it’s the way life works. People make judgments. You have to kind of learn to roll with them. You will have to, when you win, be gracious and know that part of that was some luck. People liked you, for whatever reason, better than somebody else. A lot of it will be about loss, but it’s not a loss completely because you got something out of it. And the work you put in is your win.

Once you put something in a competitive mode, you can’t kind of rest on your laurels or not give it all. There’s something riding on it. So that’s a motivator. That’s a reason to go all out.

T&W: What would you say is the hardest part of the program for you, and for the students?

LE: I don’t think in terms of that. I think the whole thing is great from the get-go. From getting kids together in a room the first time who want to know more about this, then keeping them interested. Most of them are when they find out what it is. The memorization. People are discouraged because you have to memorize, but these are short, and you have plenty of time to do it. I don’t think there is a hard part. I just don’t! I think it’s all pretty cool. If you like poetry, it’s a gift. It’s so much fun.

T&W: Thank you for doing this today. Is there any one last thing you want to say about Poetry Out Loud?

LE: You can perform something and have a good veneer on something, and it can kind of look good. But what I want so much more from these kids that do this is to get under the skin of the language. Not to say what was the author thinking here, because I don’t think we ever know that. But what are the possibilities that these words give us, this language gives us? For me, an honest performance is what I’m looking for, more than anything. To try to pull away from anything that’s slick.

I try very hard to say this is not about you, in a way. Yes, you’re the vessel, but this is about something else. In the Billy Collins poem “Marginalia,” he says, “Irish monks in their cold scriptoria/ jotted along the borders of the Gospels.” And near the end he says, “anonymous men catching a ride into the future/ on a vessel more lasting than themselves.” Something like that is almost what I want the kids to think of. It’s not about immortality, but it’s about look at this. I’m keeping this lovely thing alive. These wondrous words alive.

If you are in New York State and want to learn more about Poetry Out Loud, please email pol@twc.org. To find POL coordinators in other states, go to the national Poetry Out Loud website.

Poet, playwright, art historian, and social innovator, Dave Johnson is the author of two books of poetry, Dead Heat and Marble Shoot; and two plays, Baptized to the Bone and Sister, Cousin, Aunt. He is the co-translator and dramaturg of two Italian stageplays, the international bestsellers Gomorrah and Super Santos. His visual art curatorial work includes exhibitions at the Queens Museum of Art and at the Milan World Expo. Dave founded and directs Free Verse, a publishing house and working artists’ program born in the New York City Department of Probation waiting room. His awards include fellowships from the Rockefeller Brothers Fund and the Ford Foundation. Dave teaches at The New School and Montclair State University. His present work centers on women artists of the Italian Renaissance.