So I’m talking all the time about the power of words, about how words matter, about how a poem can help us make sense of the world around us, etc., etc., when out of the blue wide-eyed Aniya, a third-grader here in Detroit, raises her hand and asks me a question I am not prepared to answer.

“But Mr. Pete,” she says, “what if there were no words?”

What if there were no words? I don’t know at first what to say to this. “No words?” I ask.

Aniya is her own kind of quiet mirror. “No words,” she says back, and tilts her head, and waits for what I might be able to tell her.

I don’t know what to say to this question. I have no words for this. I am a wordless man, a one-winged bird—my flight going down—with no nest to call my own.

But I am here, as Mr. Pete the Poem-Man, to teach these young birds how to fly. So I must fly, even if the wind is gusting in my face, blown here by the voice of Aniya, a name that claims to mean (yes, I just looked it up), that God has shown meaning.

What does it all mean? Someone, please, I say to myself, show me what it all means.

It’s true that the best poems, I tell my students often, deliver us to a wordless place. What is it that Charles Simic writes in his notebook? Poetry is the orphan of silence.

And so, like an orphaned poet struck mute by Aniya’s question of all unthinkable, unanswerable questions, I have no choice but to at least try to offer up some kind of a response.

I am her teacher after all, yet sometimes it’s our students who do the teaching.

“I don’t know,” I begin my attempt, this mere confession. “If there were no words,” I say, “would we even be here right now? Would we even exist if the word ‘boy’ or ‘girl’ or ‘poem’ wasn’t here to exist?”

Deep waters to try to cross—frozen sea or not—I realize, for third-graders on this mid-January afternoon in Detroit.

But it’s true, and it’s something I believe in: the power of words to make a thing to be.

Picture, in other words, the world before words, and that moment when whoever made language come to be pointed at one thing—sky, water, cow, mud—and said that each of these things of the world was also this. And here, with their mouths, they made a sound? Drew a picture on the stone wall of a cave? Is that how the first words were made?

“In the beginning was the Word,” I offer this up, as a kind of consolation (to whom, I don’t know, myself?).

I hold my breath with that.

I’ve always believed in the notion that all things, all that we see—oh so many nouns waiting to be turned into metaphors—that it all began through language, yes, with words, the naming that takes place to conjure up and better understand the world that is around us.

It’s the common tongue that all of us human birds sing through, this language and idea of the Word.

I’ve always found pleasure and consolation in this: that when you take the Word and slide in the letter “l,” “word” becomes “world.” One tiny letter—a stick, a twig, the trunk of a tree, one side of a house—separates light from dark and day from night and earth from all the oceans.

Our words, I’ve told them often, are how we make our worlds known.

Raymond Carver writes, “Make use of the world around you,” and I’ve held those words up to them as an invitation to be inspired by what they see and hear around them, not to mention all the things they do as they interact with their world.

A poetry of the everyday.

The Word as ritual, as daily bread.

Or what the French poet Char says: “You have to be there and be ready when the bread comes fresh out of the oven.”

Aniya is the baker of this day, of the poems that are about to born and made on this day of “what if there were no words.”

“There is poetry,” I tell them, “right here in this room, here out this window,” and I point to and through window.

But would “window” be a thing, I wonder, if there was no word to say what it was, back before “window” was the thing that it has become?

Would “glass” be what it is in relation to “window,” would “sky” seen through “window” be a blue thing for us to see and for the birds in the sky to fly through it?

Would “wheelbarrow” be a thing to depend upon had not “wheel” and “barrow” been forged together to make them both a single compound word?

This is what young Aniya—baker of word bread—has blown my mind open to: the possibility that without a word the thing itself might not exist.

Words and their sense of purpose.

We are here because of words. I am here in this room with my red wheelbarrow glazed and glistening with words.

Words lead to deeds, a saint once said some four centuries ago.

Yes, words last. They endure. Are made to last. I believe this to be true.

Every word, so wrote Emerson, was once a poem.

I hear this voice inside my head.

So much depends upon.

I have no choice. I am standing at the threshold between words and silence. As a writer, as a man of the word, I must break down this wall. I must push through this door.

Our words, Hafiz wrote, six centuries ago, become the house we live in.

So I decide to answer a question—the question of the child—by asking back a question: a game within a game.

“What would a world without words be like?”

“Would it maybe be like a night sky without any stars?”

“A world without words,” I go on, “would it maybe be like a river that doesn’t have any fish in it.”

“A world without words—”

I stop myself from saying more.

“You tell me,” I tell these students, Aniya staring up at me among them. “What would that world be like?”

Here is some of what they say.

A world without words would be like:

—a shoe without shoe laces

—a radio with no music

—a rainbow with no color

—a king with no crown

—a tree with no branches

—a library with no books

—a person with no voice

—a country with no president

—a lost dream without a person to dream it

You get the picture, yes?

The words, dare I say it, help us to see, yes?

Then I ask them to think about Aniya’s question—“What if there were no words?”—and to come up with their own questions for us to think about if, in fact, there were no words in this world.

How would we speak?

How would we sing?

How would I say I love you?

What would we do with our mouths?

Why are we even alive if we can’t express ourselves?

How will I know my name?

How would we know where we are or how to get home to where we live?

Would we even exist?

One little girl who, the week before, when she told me she didn’t know how to write a poem, I simply told her, “Write a poem about not knowing how to write a poem.”

Her question on this day of “what if there were no words” is, “How could Mr. Pete tell me to write a poem about not knowing how to write a poem if we didn’t have words?”

Oh how I love how these kids “make use.”

These kids, yes. And then there’s those other kids, too, and maybe especially so, who too often go unheard during classroom conversations, who are oftentimes the ones whose voices get drowned out by the students who are comfortable with words, who are not afraid to speak.

Take James, for instance. You wouldn’t know he was here if speaking was what made us visible and present in this world.

James who does not often talk, or raise his hand when asked, “Who wants to read their poem?”

And yet, his words, his poems—yep, you guessed it—are oftentimes the most powerful poems of the day.

Today is no exception.

James who carefully chooses his words, his handwriting precise, dare I say nearly perfect.

James who doesn’t generate the most words, in terms of bulk, but in terms of heft: he says what needs to be said, in order for his words—his poems—to be felt.

Here’s James’ poem, “If There Were No Words”:

If There Were No Words

If there were no words

our world would be like

a chair without legs

a tree without roots

a car without wheels

a dog without legs

a cat without a tail

a word wall without words.If there were no words

how will I know my name?

How will I say I love my mom?

How will I say Amen?

Dare I say that a poem is a kind of prayer?

Here’s a few other poems written on that day where the possibility of a world without words was soon proven impossible.

We do have words, our bread at the table.

We do have words and we are trees whose words are roots that hold this great Earth spinning here in space.

What If There Were No Words?

By Michelle (grade 3)If there were no words

people would dance the

thing they are trying to say.If there were no words

how would my friends talk to each other?How would we be able to tell

people they are bad or good?How would we be able to sing a song,

or draw a word, or be able to write on this paper?If there were no words, would I be invisible?

If There Were No Words

By Jacob (grade 5)If there were no words

the planet Earth would not spin

leaving it dark on all the people.If people go to space

they would float and not accomplish

their mission.If people went to the park

it would be too late to play anything.If people ate dinner it would

be cold and have no salt or pepper.If people went to sleep they

would have dreams about nothing.If there were no words our world

would be like a rainbow with no color,a monkey with no tail,

a bed with no cover or pillow,a skunk that smells good,

a refrigerator with no food.If there were no words

how will there be any color?What would we do for fun?

Who would we turn to?

If We Didn’t Have Words Our World Would Be Like

By Clarence (grade 5)—a car with no wheels

—a house with no roof

—a person with no bones

—a picture with no color

—a school with no teachers

—a book with no pages

—a table with no legs

—a poem with no title

—an ocean with no water

—a wallet with no money

—a king with no crown

—a dog with no tail

—a cat with no whiskers

—a fan with no air

—a car with no motor

—a park with no swings

—a ring with no diamonds

—a groom with no bride

It’s true: the world can sometimes make us feel, what? Stranded at the altar. Shipwrecked on a deserted island. Dropped to the pavement like a penny that has lost its presidential face. Which is why it’s important to know that words are what we do have in this world, and sometimes it can feel as if that words are all we do have: to guide us, to help us make sense, to bring us back when we are cast away, when we find ourselves washed up on unfamiliar shores.

Words, in other words, it’s good to know—and Orissa’s poem speaks to this—we carry them by our sides.

Words Being By Your Side

By Orissa (grade 5)Beads put together to make a necklace.

Words pretty as tiny sparkles

of glass dancing on top of water.Words

feel like being in heaven or

standing under a dark cloud.Words follow you like your shadow.

Words sweet like honey.

Words are always waiting for you.

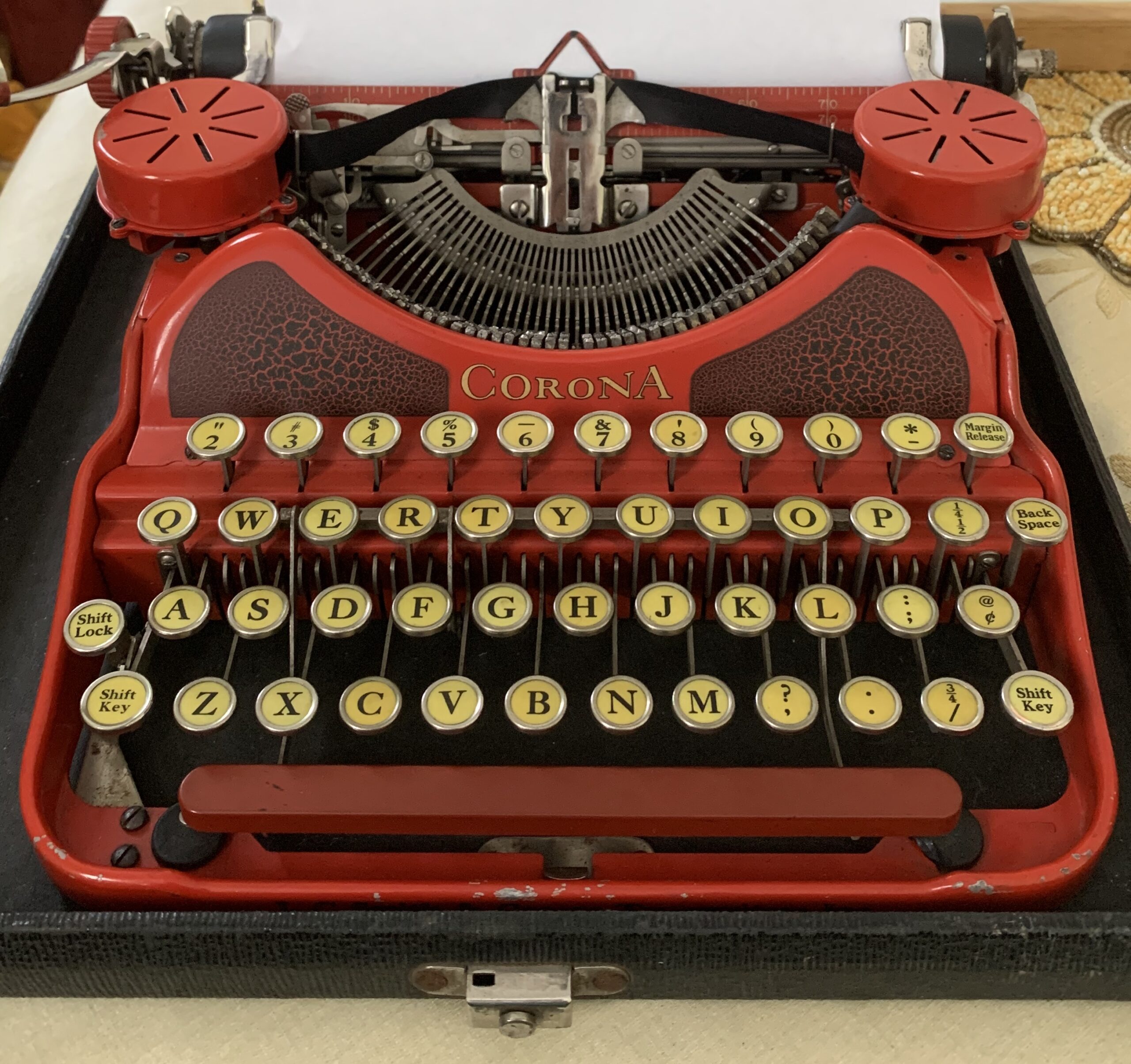

Image (top) by Deja Barnes

Peter Markus is the senior writer with InsideOut Literary Arts Project of Detroit, where he has worked as a writer in the public schools for the past 20 years. In those 20 years, he has also published six books of fiction, the most recent of which is The Fish and the Not Fish. He also edited, with InsideOut founder Terry Blackhawk, To Light a Fire: 20 Years with the InsideOut Literary Arts Project, published in 2015 by Wayne State University Press.