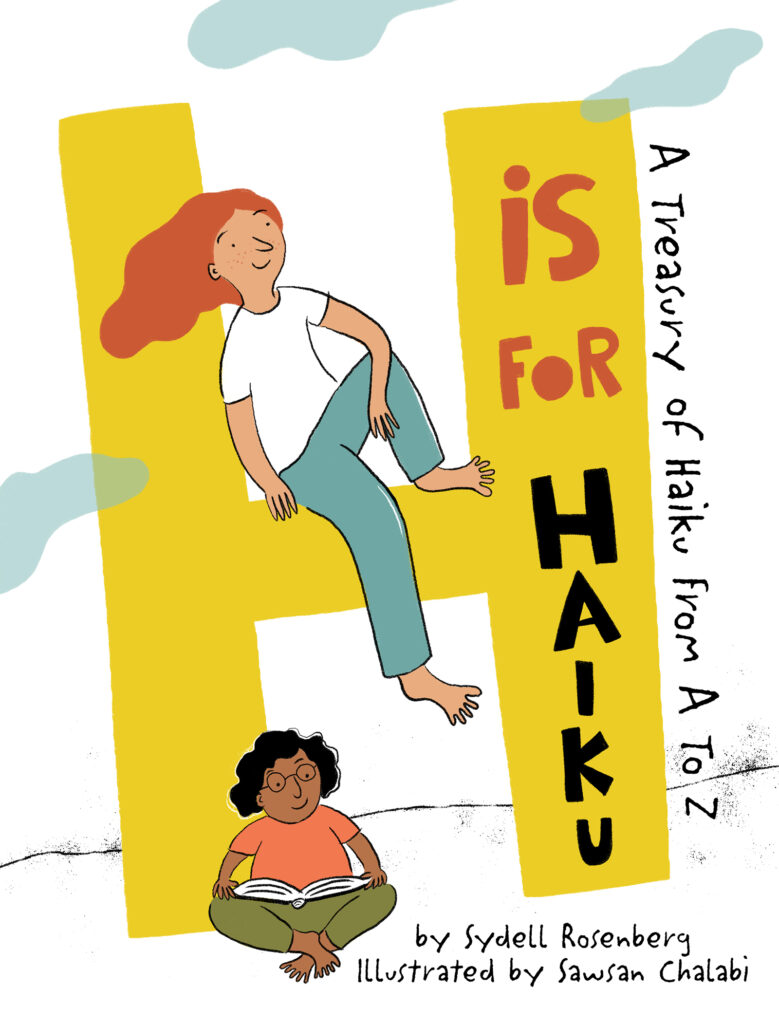

Poet and Teachers & Writers Collaborative teaching artist Erika Luckert uses Sydell Rosenberg’s children’s book, H Is For Haiku: A Treasury of Haiku from A to Z, to introduce young students to this poetic form. The National Council of Teachers of English chose H Is For Haiku as a 2019 Notable Poetry Book

Show students the book H is for Haiku, and tell them that nothing is too small or insignificant for poetry. Today we’re going to be reading and writing haiku, a type of poem that makes small moments big.

Show students a picture of Sydell Rosenberg, and offer a bit of background about the author.

Sydell (Syd) Rosenberg was a teacher in NYC Public schools, and a published writer and haiku poet. She went to school in Manhattan, then went on to attend Brooklyn College and Hunter College, where she earned a masters degree. Her short poems were published in various magazines, newspapers, and anthologies, and one of her haiku was even displayed in Times Square on an old movie theater marquee!

Then, invite them to read one of her haiku aloud:

Up and down the block

homeowners mate the covers

of gusted trash cans.

Ask students:

- What do you picture from these words?

- What does the poem make you think about?

- How does the poem make you feel?

Encourage students to engage with their imaginations, senses, and experiences, and share different ideas about the poem. Lead them to focus in on details of the language—particular lines, or even particular words that stand out to them. Then, draw students’ attention to the way the poem makes a small moment big, or important—it’s just people putting the lids back on their trash cans, but this poem makes us pay attention to that small moment, that bit of time after a storm or a gust of wind when things are put back where they belong.

When students have shared their ideas, you might choose to show the illustration from the book (by Sawsan Chalabi) before moving on to the second poem.

Holding umbrellas

children, like rows of mushrooms

glisten in the rain.

Again, ask students:

- What do you picture from these words?

- What does the poem make you think about?

- How does it make you feel?

Once students have had a chance to share their ideas about the second poem, draw their attention to its form by asking questions. You might even put both poems up on the board so that they can compare.

- How many lines does the poem have?

- Are the lines long or short?

- How many syllables does the poem have? Invite students to clap out the syllables aloud.

As students make observations about the form of the poem, write the features of a haiku on the board:

- A haiku has 3 lines

- 1st line: 5 syllables

- 2nd line: 7 syllables

- 3rd line: 5 syllables

- A haiku makes small moments BIG!

Brainstorming:

Ask students, what are some other small moments that could become a haiku?

Together, brainstorm a list of small moments that happen in students’ daily life. For example: waiting for the bus, climbing the stairs to your apartment, lining up for lunch in the cafeteria, taking your dog for a walk, watching a neighbor take out their trash. As students brainstorm, push them to be specific in their descriptions. If a student offers “going to school,” ask them to describe how they get to school. If a student offers “doing my homework,” ask them to describe the scene—where they do their homework, what tools they use.

Writing Task:

Once students have brainstormed a good number of ideas, and all of them are thinking about small moments in their lives, present the writing task:

Pick your own small moment and turn it into a haiku! You can pick one of the ideas that we brainstormed, or another one we haven’t mentioned yet. Remember, you only have three lines!

A note to teachers on syllable count: While the traditional Japanese form has a strictly regimented syllable count, many modern translators of haiku, and haiku poets, agree that in English, the syllable count should be less strict, because syllables in Japanese operate very differently from the way they do in English. For teaching purposes, I sometimes still like to use the more traditional syllable count because the constraint pushes students to be more creative with their language. However, if a student is finding the restriction unreasonably frustrating, you might encourage them to “cheat” a little. Or, you might even encourage the students to choose their own syllable count as a class to adhere to—7,9,5 for example, or 6,8,4.

Wrap-up:

Ask students to share their haiku aloud. Encourage them to make the moment BIG by reading slowly, and projecting their voice to the class. You might even invite them to read their Haiku twice!

Extensions:

In Syd’s book, each haiku is beautifully illustrated with collage images. When students have written their own haiku, invite them to design a page that presents their haiku in a visual form. This follows the Japanese tradition of Haiga, where haiku poets would create a painting or other visual representation (photography, collage—the options are many!) to accompany their poetic work.

Syd’s book, along with being an illustrated collection of haiku, is also an alphabet. Assign each student a letter of the alphabet, and, as a class, create your own haiku alphabet for display. Encourage students to make use of alliteration with their assigned letter.

Poems from H Is For Haiku: A Treasury of Haiki from A to Z. Text © 2018 Amy Losak. Illustrations © 2018 Sawsan Chalabi. Reprinted with permission from Penny Candy Books.