Early in my career I caught a glimpse of how exploration of art and creativity can powerfully influence written language. I was a rookie English teacher in a large urban school district with a high Hispanic population in southern California. While the focus of learning in my English class was speaking, listening, reading, and writing, I encouraged my students to use art to support and enrich their writing assignments.

My twelfth-grade literature class was thought provoking with an ambitious reading list, including books such as The Metamorphosis and Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. A number of challenging writing assignments also complemented the literature. The first writing assignment of the school year was a simple self-introduction essay. The essay would allow me to assess my students’ writing, while providing some insight about their experiences, passions, goals, and dreams. I found that many of the students’ essays lacked depth or evidence of clearly understood elements of the writing process. Some papers read like stream of consciousness filled with run-on sentences and an absence of paragraphs. Other papers were filled with double negatives and numerous spelling errors. Only a few students presented papers with complex sentences, descriptive phrases, and strong vocabulary.

Teachers’ expectations play an important part in student academic success. Minority and immigrant students, especially Black and Latinx boys, are often subject to tracking and low academic expectations (Hallinan, 2004). Many of the students I taught were used to having teachers who believe certain students lacked academic potential. By the time these marginalized students reach twelfth grade, they are often burdened with the stigma of being labeled “lazy” by teachers who feel some students will always write less than others, or by teachers who give up trying to challenge their students to become better writers.

In my class, each student was required to have a writing journal. The students were assigned to write continuously for a full ten minutes each day at the beginning of class. I noticed one student struggling with this assignment. His name was Roberto, and he wore a tough guy stance. He sat at the back of the classroom, was usually quiet, and rarely participated in class discussions. For the first several days of class, Roberto rarely wrote at all. Some days I noticed him struggling to stay awake.

One day, I asked Roberto why he was so tired. He explained that he was a tagger. My understanding of taggers was that they stayed up late at night, often into the wee hours of the morning, painting graffiti on unsuspecting walls. While tagging was a way of sending a message to gangs on the street, it might also be seen as a form of artistic expression. Following my conversation with Roberto, I noticed he kept a piece of paper hidden beneath his journal. Catching a glimpse of it, I saw big, bubbled block letters, darkly outlined and penciled in with hash marks just like graffiti seen on train cars and freeway underpasses. Evidenced on this hidden paper was proof that Roberto was working on his visual art in class, rather than on his writing assignment. Staying up late at night and practicing during the school day, it was obvious that Roberto was passionate about graffiti. I saw Roberto’s concentration on street art as an opportunity to connect while he was in my English class. Rather than reprimanding him for drawing instead of writing, I tried to connect his creativity and passion for the one with the other.

In an attempt to lure Roberto to write, I suggested that when he had filled up one half page then he could work on his drawings. At first he grumbled, “But I just don’t like to write, Mrs. Pell. And I’m too tired.” Other days he would argue, “I don’t have nothing to write about!” Finally, I encouraged him to write about tagging (his art), and about how he feels when he’s out applying his art (tagging) with his friends. After steady encouragement over several days, Roberto began to write a little. He also started sharing his tagging designs with me. I noticed that his sketching transformed from words to pictures, from outlined characters of his name to pictures of his crew, whom he called his “Homies.”

Each Friday the students worked on their writing for half of the class period and Roberto and I would meet one-on-one to discuss the elements of his writing. At first, I offered only encouraging comments. I complimented his sentence structure and the correct use of basic grammar. Over time, I would challenge him to use action verbs and rich adjectives to “show” rather than tell what happened in his story. By the end of the month, my continued interest in Roberto’s writing persuaded him to write a story which captured the significance of his hobby. He continued writing steadily week by week and I offered constructive criticism, reminding him to re-read his work to fix spelling errors and combine sentences to eliminate a choppy narrative.

Eventually, it seemed that Roberto began to see that both art and writing were worth creative effort. Soon Roberto had written a full page at the end of ten minutes. He continued working on his writing each day, crafting a story about his experiences. His story became three pages, then four, then five, and I sometimes caught Roberto smiling as he flipped through the pages of his journal. Roberto worked eagerly. He was busy, focused and engaged.

Yong Zhao (2018) in his book Reach for Greatness states that students come to school with unique skills and knowledge, which when recognized can be starting points for further development, possibly even cultivating the potential for greatness. Roberto’s unique skill and knowledge was his art that he expressed through tagging. Recognizing his skill and passion for art (while not condoning his tagging) was a way to promote his potential in other areas, namely his writing. Gradually, Roberto expressed himself more with pencil and paper than with paint cans and walls. After reading Roberto’s journal, I could see his creative writing improving because of his interest and investment in the topic. His journal became a testimony of an artist who was confident, skilled, and whose leadership even inspired some members of his crew. Roberto admitted, “I don’t go at night so much anymore. My homies thought I was crazy but now they’re cool with it. They get that this is important to me.”

Writing about his experiences with gangs and tagging influenced Roberto’s writing, and each time we met for one-on-one feedback, his work steadily improved. Roberto’s artwork was the bridge to dynamic creative writing that motivated him to reach academic success. Most of his stories included details about his crew, their territory on the streets and stealing paint. After we read “On the Sidewalk, Bleeding” by Even Hunter, Roberto recorded in his journal, “We don’t have knives. That’s stupid. We’re taggers, not gang bangers. My crew takes off if we see another gang coming our way.”

Toward the end of the school year, I suggested to Roberto that he consider attending a local community college to pursue his passion in art. He chuckled softly at first, looking at me as if I was teasing him. No one in his family had ever attended college. I felt perhaps that suggesting a college close to home, near his family, would sound doable to Roberto. I encouraged him to think seriously about it. The final written assignment for the school year was a research paper on the theme: The American Dream. I challenged Roberto to write a paper about what his future might look like as an artist. He enthusiastically took on the task and turned in a lengthy paper filled with details and examples depicting his future. He described what an artist does, the variety of tools, the different mediums, and common practices. He also described his own passion for color, sketching, painting, friends, locations, work, and hope. He wrote about his dream for a family and being able to support them with his artistic talent.

The last week of class Roberto approached my desk and said, “Look Mrs. Pell, I’m applying to college.” In his hand was a pamphlet from a local college. He said, “I’m going to major in art and be the first in my family to go to college.” I smiled, feeling proud of how much he had grown in such a short time.

Not all endings to the school year are as positive as Roberto’s. I remember one student I taught named Devonte. Although he was in the eighth grade, he was reading and writing at a second-grade level. Devonte was energetic, excitable, and distracted. More than once he stepped up close, got in my face and in front of the class shouted, “Who do you think is in charge here?” Another favorite habit of his was to yell out loud from his seat, “I ain’t gonna to do no work today.” His cries for attention tested my patience and I found myself pulled into Devonte’s challenges.

The climate of the classroom changed when these outbursts surfaced. I would give warning of an ensuing detention if he did not follow the rules, and he would continue to banter. I wanted to connect with Devonte but struggled to find a way to motivate him to write or read. After a semester of ups and downs, I failed to find a way to persuade him to be productive. At the end of the semester, Devonte was transferred from my class to another class and I was left to reflect on the matter.

When comparing the resources I had teaching in the late 1990s and the availability of resources in education today, I recognize that using technology might have been a way to reach Devonte right where he was. As an energetic communicator, Devonte might have used a digital platform for recording his stories or singing or typing instead of only writing by hand. There could be a number of reasons why Devonte failed to thrive in my class. I am left thinking if I could have connected with him on an emotional level, finding what he was passionate about and what was most meaningful to him, Devonte and I might have continued to learn from one another.

In his book, Lives on the Boundary, Mike Rose (1990) makes the case that remedial students, many of whom are young people of color, lack literacy skills due to the scarcity of supportive social conditions. As educators, it is our responsibility to consider how our curriculum and teaching are appropriate and relevant for all of our students. Supporting a student’s creative talent and passion in the classroom, whether in history, English, science, math, or art, can lead a student to greater knowledge of self and a deeper understanding of any subject matter. The aim is to build a bridge, a social-emotional connection, between student interest and teacher expectations.

Having high expectations for all students begins with knowing the student. Knowing the student means looking at the whole person. A student’s work, like Roberto’s, is more than an assignment to be graded. It is an extension of a person, an individual whose passion and creativity might be unexpected or hidden by limited perceptions. Noticing and acknowledging what a student is passionate about can influence a student’s academic success and their future. As Scott Barry Kaufman (2013) states, in his book Ungifted: Intelligence Redefined, recognizing creativity and having high expectations in the classroom can ignite motivation, inspire action, and set a positive trajectory toward the future for all students.

Seeing Roberto’s tagging as the potential for productive artwork was the starting point for developing a respectful and trusting relationship with him. The recognition and growing appreciation of Roberto’s creative writing not only affirmed his creative talent, but also raised his self-esteem, increased his classroom engagement, improved his academic writing, culminated in a passing grade for the class, and ultimately led to high school graduation. The attention to creative writing, connected through his artwork, planted a seed of hope for a future that Roberto previously never imagined. He experienced ideal individual growth, progressing from a graffiti tagger to creative writer to college-bound artist. High expectations and meeting students where they are is an art in itself. We need to look for unique skills, passion, and creativity in our students, then act on the opportunities to build a bridge.

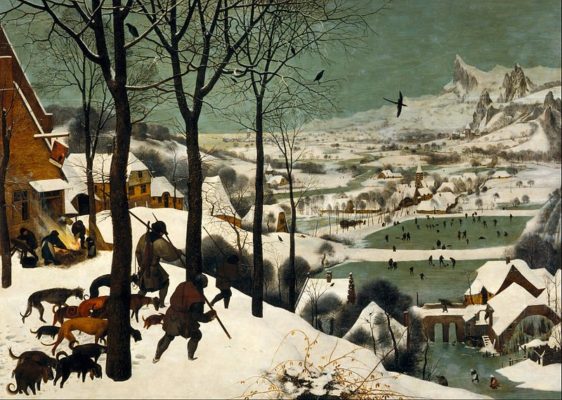

Image (top) from African Genesis.

Beverly Pell has worked in the education field for over twenty years. She has taught in urban and suburban schools and also homeschooled her two daughters. She recently competed her PhD in educational leadership and policy studies at the University of Kansas. She enjoys inspiring her students to become active listeners, readers, and writers by reflecting on their choices, dreams, and ambitions.