T&W Magazine editorial board selected Candice Iloh’s “Remaining Nameless: How Writing Anonymous Personal Narrative Essays Transformed a Bronx Classroom” as the third place winner for the 2022 Bechtel Prize. The prize was awarded for an essay describing a creative writing teaching experience, project or activity that demonstrates innovation in creative writing instruction.

The Bechtel prize is named for Louise Seaman Bechtel, who was an editor, author, collector of children’s books, and teacher. She was the first person to head a juvenile book department at an American publishing house. As such, she took children’s literature seriously, helped establish the field, and was a tireless advocate for the importance of literature in kids’ lives. This award honors her legacy.

Listen closely: you are not to write any identifying information anywhere on the page. No first or last name. Nothing you are called in this class. Nothing that would give you away. I will give each of you a number and you will use it on every document that we use to build the essay. Every time you turn something in that has anything to do with your story, only your assigned number should be at the top.

For the next few months, the only person who will know which essay belongs to you is me. Even when you receive your final grade, it will be assigned to your number.

In this class you are nameless.

Just a few months before I gave these instructions out to my two classes of 25 students, I was hired by the school to run its creative nonfiction class. My task was to foster an environment in which students between grades 9 and 12 would write content for the school magazine. Simple. A cool article about whether uniforms were oppressive or not here. A funny interview with the school janitor there. A crossword puzzle filled with fun facts about each of the teachers that none of the kids knew and, sometimes, the continuation of a cartoon series drawn by the class artist. Perhaps a featured poem contributed by another class. Coming in, that seemed like the assignment judging by what I’d seen of the previous issues published before I’d arrived. But who was I fooling? I’ve never not done the most.

Sure, I wanted to continue the legacy of the laid-back classroom environment where I, the new, cool Writer-in-Residence maintained the no-fuss appeal of an artist who’d been brought in to offer something that the kids actually wanted to do without twisting their hands. I wanted the kids to like me and not feel further blanketed by the stress of more grades or projects taking away their beloved free time. I wanted to let them be. And I did that for the most part. I let them call me by my first name, which is still my preference. I told them about my personal life. I answered questions honestly about the real world and let class time be guided by what they were into and obnoxious things I’d found on the internet to engage them in ways they wouldn’t expect in school. I let them use the language that felt most comfortable to them as long as it wasn’t aggressive or distracting from what we had to do for the day. Generally, I did my best to create the kind of space that was safe enough for them to be themselves in because, as far as I was concerned, that wasn’t happening enough.

Of course, it wasn’t entirely a pressure-free zone. I was still bogged down by having to follow school rules that I didn’t agree with. My kids had to deal with sharing a building with two other schools and this building was right across the street from some pretty ‘active’ housing projects that many of them lived in. Outside of my classroom was still a chaotic neighborhood in the Bronx that asked them to grow up at lightning speed. So, the stress was often thick with residue of conditions I had little control over no matter how safe I tried to make our space. This often included various school professionals barging in during our class discussions, frequent testing, and last minute schedule changes that left me feeling like my presence there was an afterthought. A placeholder. A glorified babysitters club where parents never showed an interest in what their children did all day. Almost no one ever observed my class. For a while I felt down about that until I realized something: I could run this class however I wanted.

But hold on. Before you go thinking I went completely rogue and threw out all teacher-student decorum and such, pump the breaks. That’s not what happened at all. The idea that came to me was way better than that. Hear me out.

Creative nonfiction. School magazine. Essays. High school students. New York City. Drama. Are you following me yet? Alright I’ll stop speaking in code and go into the specifics:

The benchmark of success with this school was that I simply had to accomplish three to four issues of the magazine by the end of the year. What was included in them was up to us. But as a writer, I saw a unique opportunity for us to go further. I absolutely could have kept things light. Made it easy for kids to get their grades without digging too deep but that wasn’t really my style. And it wasn’t theirs either. A lot of people think kids—especially high school kids—don’t want to do any work. That they’d rather take the easy route that requires the least amount of thought or personal investment, but I quickly realized that was false.

I’d come up with a curriculum for the year where I assigned all different kinds of articles they could sign up to write, ranging from current events to sports to interviews. And I had their attention for maybe the first month or so. But then the boredom took over and so did the trauma fatigue of reporting on the goings on of the world. I was confused at first though. I was bringing them what I felt like were the goods. News plucked straight from social media and prompts that I told them they were free to run with. But after the first issue we quickly started coming up short. By the time kids got to my class, they were exhausted from the day and the last thing they wanted to write about was everything going on around them.

So I thought: maybe I should try to get them to write about what’s going on inside them. Obviously, that’s not an original idea. The other Writer-in-Residence taught poetry and I’d been a teaching artist for several other programs teaching poetry myself for the same reason. But I was thinking about the personal essay. Narrative essay centered on a personal experience that had a lasting impact on who they’re becoming.

I presented the idea to the class thinking that, because the caveat was that they could write about whatever they wanted, they’d jump at the idea. But they didn’t. Both of my classes lacked any of the enthusiasm that I thought I’d be met with. Many of my students immediately freaked out at the idea of talking about themselves and most of them thought their lives were grossly uninteresting. Why would anyone want to read a whole story about me? so many of them thought. A large majority of my roster felt their lives were too mundane to waste on five hundred words. So, I made it even more interesting.

Would you feel the same way if it were anonymous? The consensus was that this surely was a trick question. And I hadn’t been expecting the responses: that they were down to write candid stories about experiences they’ve had as long as no one knew who wrote them. I had to think quickly about how to keep this promise.

The next day I came into class with numbers assigned to every kid on my roster. The names associated with numbers were on a document on my computer separate from any public files and the folder I’d brought into class only had numbers. Nothing else. I met with each student individually to give them their number and brainstorm after I led an icebreaker, plus a group discussion, on defining moments: specific life events that shifted a person’s perspective or identity, thus shaping their world view and personal aspirations. This took a lot of work. We had several classes that looked like this to get the wheels turning.

We watched Youtube videos of artists and athletes telling childhood stories. Studied movie clips featuring coming of age story arcs. Read articles and social media posts about all different kinds of people who’d dared to bare their souls to the public after life-altering events. It was all a daily exercise in getting them to see that their lives were worthy of shine instead of shame. After about a week or two of this, I met with all of them again. One by one, I took them out into the hallway where no one was around, and they’d tell me the idea for their essays.

I want to talk about the two abortions I had, Miss.

I want to write about why I like to fight.

I want to write about the day my brother moved away from me.

I want to write about my first time.

The list was eye-opening, but not much of a surprise if you really know young people. Especially young people who’ve had to grow up fast. Each student’s defining moment was something they either believed had only happened to them or something they knew, if they told a loved one, they would be judged.

Thank you for sharing that with me, I found myself saying over and over. You’ve really never told anyone? Not even your mother? The headshakes kept coming. Most of my students had kept moments that changed them forever buried deep inside where no one would ever find them if not asked by someone they trusted. Many of them had been prepared to keep those secrets under every layer for the rest of their lives. And somehow, they were standing in their school hallway whispering them to me.

For the weeks after, they were given Defining Moment Essay templates that followed a simple yet engaging structure: open with the moment told in first person present, provide backstory of what life was like before “the thing” happened in the body paragraphs, and in closing, talk about what you learned about yourself and how this experience shifted your world. I allowed them to first fill in the template like a worksheet, reminding them to make sure they labeled the sheet with their numbers only. I often had to erase names. It took a lot of practice. At the end of each class, they had to return the sheets to me. There was no going home with this assignment. This project will never be homework. We had to protect it from falling into the hands of strangers, family, and even their friends if we were going to pull this off.

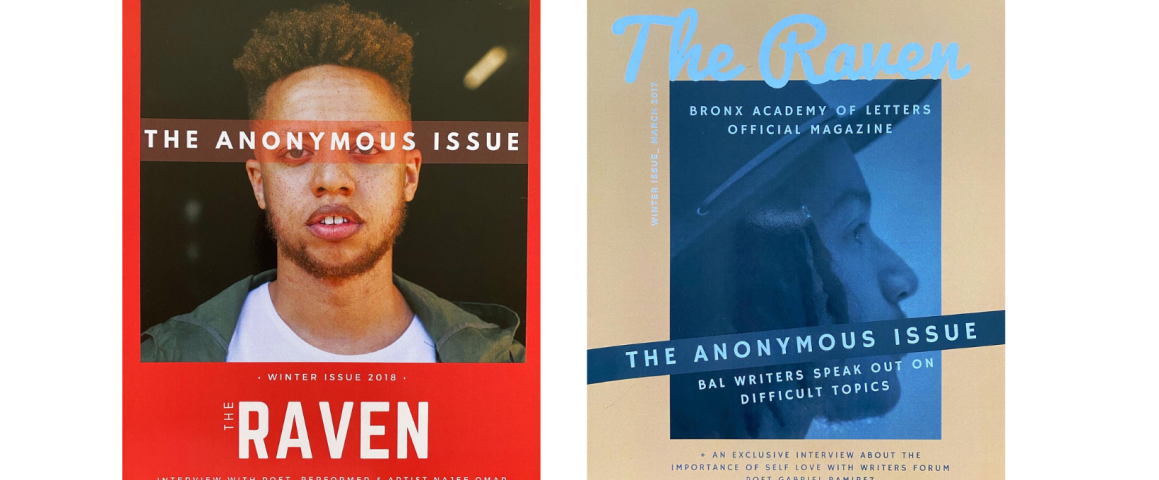

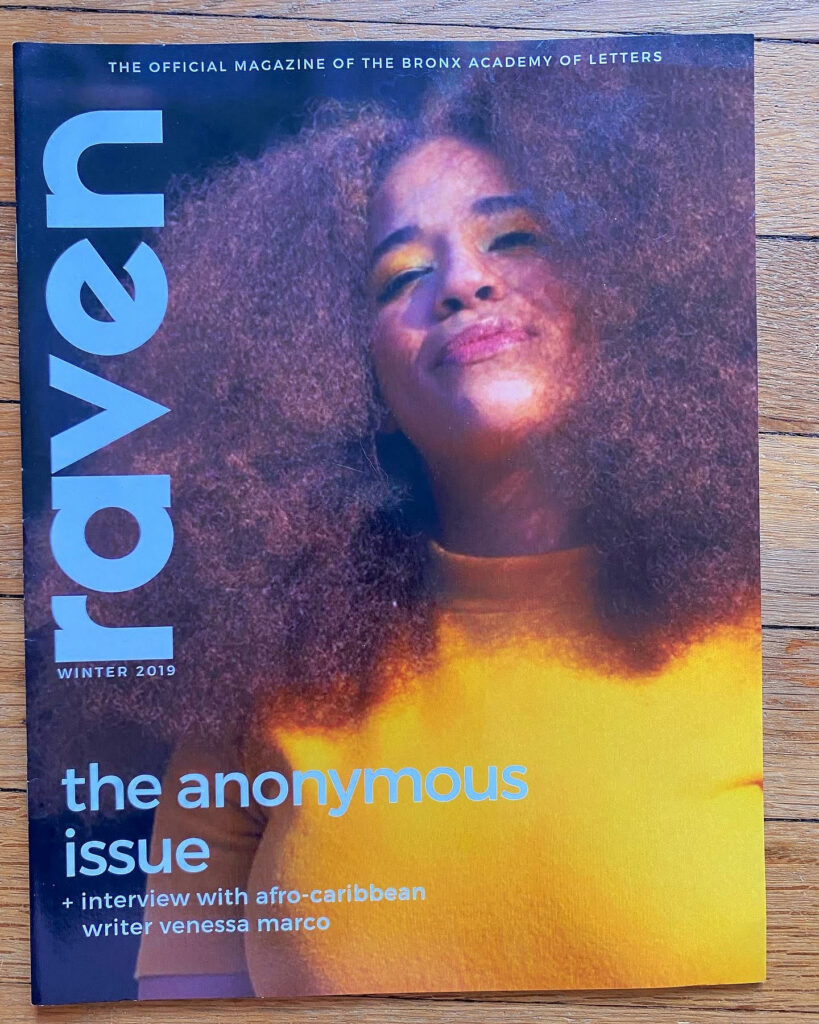

The culmination of this project was called The Anonymous Issue and became an annual tradition for the magazine during the three years of my residency. Each student was graded on their ability to incorporate the feedback they got from me into their revisions, voice, flow, and clarity—all of which were taught as ways to fill the reader’s experience with ease, rather than arbitrary rules of correctness. We spent a lot of time talking about style, use of humor, and personality. I pulled random lines from random essays while they were still in progress, so each student left class often with affirmations without anyone knowing it was for them. When the issue came out, we had a party in our classroom with snacks and music, and they all signed their names on the title pages of each other’s copies.

It was a celebration of release. They’d all learned something about the power and usefulness of putting their experiences into writing. No longer did they have to carry the burden of having to be silent for fear of public ridicule or consequence. Their stories were out in the world and deeply felt for what they were. They could experience what it’s like to use their truths to get free.

Featured image: covers of “The Anonymous Issue,” courtesy of the author.

Candice Iloh is a first-generation Nigerian American writer and dancer from the Midwest by way of Washington, D.C. and Brooklyn, New York. They are a proud alumna of the Rhode Island Writers Colony and their work has earned fellowships from Lambda Literary, VONA, Kimbilio Fiction and a residency with Hi-ARTS, where they debuted their first one-person show in 2018. Candice became a 2020 National Book Award Finalist and in 2021, a Printz Award Honoree for their debut novel, Every Body Looking. Their sophomore novel, Break This House, released in May 2022.

Photo by Justin Lamar Carter