“Peer closer: a soul and a soul. He folds over her like a rosebud in sleep.”

— Ishle Yi Park

How to bring a love of sonnets to my high school students? Easy. I was a student, once upon a time in the old hip-hop life of Queens, and I am armed with sonnets so fierce that whenever I’ve taught them, students are unable to resist. I teach the work of Ishle Yi Park, a Korean-American woman whose sonnets center on what is still forbidden for most students: interracial teenage love. The work is drawn from Angel & Hannah: A Love Story in Sonnets, published alongside Park’s performance in the 2006 Hip Hop Theater Festival.

As the sound of a fight on a playground makes the ground electric, Park’s poems shock and excite students, spur them to keep reading. Her sonnets trace the trajectory of love between Angel, a Puerto Rican boy from Brooklyn, and Hannah, a Korean-American girl from Queens. I prefer to teach the entire book, but when short on time, I choose the following three poems as touchstones: “Quinceañera Sonnet,” “Wind Sonnet,” and “Gold Hoop Sonnet.”

Quinceañera Sonnet

On Friday nights, Karin and Hannah drink Old Es

on a peeling bench at 109th Street Park,

til an amber, foamy buzz blurs the dark edges of night.

They watch boys shoot hoops like lean,heartless seraphim and test chain-linked swings,

Nike soles pointed towards heaven,

towards star-shaped leaves. Sometimes, she

wonders why they spend

long hours preening like two peacocks,shadows huge on an abandoned playground.

But tonight is Tasha’s sweet fifteen

in St. Mary’s church basement. Hannah licks her lips,

draws on scarlet liner. She puckers.

Paints herself darker, more dangerous:

a girl who can scar in the shape of a Kiss.

I’ve taught this sonnet to high school students from Oakland to Queens. In the conversations that follow, the more worldly students explain the meaning of Old Es. This always leads to much laughter and the “aha” of why the night is becoming amber and foamy. Others explain the importance of quinceañeras in a girl’s life. We find references to heaven, look up the word seraphim, and discuss the enchanted feeling of the night.

Park’s language is uniquely her own, her vision of the urban world one of living, breathing magic. In “Wind Sonnet,” Park infuses Bushwick, Brooklyn, with Technicolor surrealism. Students feel the thrill of decoding her imagery: the flags like teeth, the grains of light.

Wind Sonnet

June. Grains of light sift over Wyckoff

Avenue, dusting strollers shoved

by thick-hipped mamís with slick, gelled hair.

Tattered triangular flags blow and click

like sharp teeth above all heads.

Angel struts, clasping Hannah’s fingers.

A cool wind ripples his undershirt,

dares to lift her skirt. Young fools with easy

grins, they stroll loose-hipped down Hart Street,

say wassup to boys ribboning Dee’s

Phat Beatz, Sal’s pizzeria.

Young street king and queen; everyone knows

his name: mira Angel y la China,

they hiss. The two own the block,

walk straight into a hot wind.

In the third of Park’s poems I show my students, “Gold Hoop Sonnet,” Park provides an essential moment of self-love, and as long as gold hoops are in style (forever), this poem will sing to teenage girls who understand.

Gold Hoop Sonnet

One day she will be brave enough

to venture away from those typical gold hoops,

from parroting her mean friend’s laughter, or

sitting on the stoop

for hours, trying to look half-fly/half-tough,sucking on a sour apple Blow Pop,

listening to the boom box’s latest version of bad

hip-hop—one day

she will look at her rough, scarred face

in the compact mirror without her Mac eyeliner,

and she will stophating those young, haunted eyes.

I hope a slant of gold light will hit her cheek

just right, and it may come as a surprise

to her how fine she really is. Fabulous. Sleek.Soulful ~ full of her own juju and mystique ~

a rose fury! Black lightning when she hits the

street.

Students are hooked. I remind them they are reading the dreaded sonnet. They disbelieve. I show them the 14-line pattern, rhyme schemes, iambic pentameter. We count syllables, label rhymes, and discuss how Park’s sonnets weave loosely through the forms, Petrarchan, Spenserian, Shakespearean, both celebrating and shunning the form’s limitations.

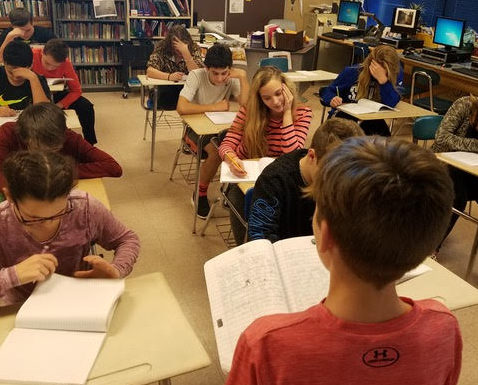

Finally, I ask students to imagine a moment of intense feeling, whether it is desire, loneliness, hatred, or awakening. I have them spend a little time entering this moment. Then I ask them to write, not directly about the emotion, but about their surroundings, to give place details, such as the ones Ishle Yi Park used to describe 109th Street Park, and to imbue these details with the chosen feeling through original metaphors and description. Students have the option to write in sonnet or sonnet-inspired form.

The blessing of writing with youth is that they sometimes just need to be given permission. Ask them to write something strange, funny, and unique, and they will.

Notes:

“Quinceañera Sonnet,” “Wind Sonnet,” and “Gold Hoop Sonnet” all reprinted with permission of Ishle Yi Park.

This article was originally published in Teachers & Writers Magazine, Vol 43, No 3, Spring 2012.

Rehman’s dark comedy, Corona, was chosen by the NY Public Library as one of its favorite books about NYC. She is co-editor of Colonize This! Young Women of Color on Today’s Feminism and author of the collection of poetry, Marianna’s Beauty Salon, described by Joseph O. Legaspi as “a love poem for Muslim girls, Queens, and immigrants making sense of their foreign home—and surviving.”

Her new novel, Roses, in the Mouth of a Lion, is a modern classic about what it means to be Muslim and queer in a Pakistani-American community.