We have finished writing the most recent drafts of our personal narratives, the first major writing assignment of the middle school year, our first attempt to show the world how powerful our writing can be, our first courageous leap onto the Velcro wall, where our work will stick and hang for everyone to see.

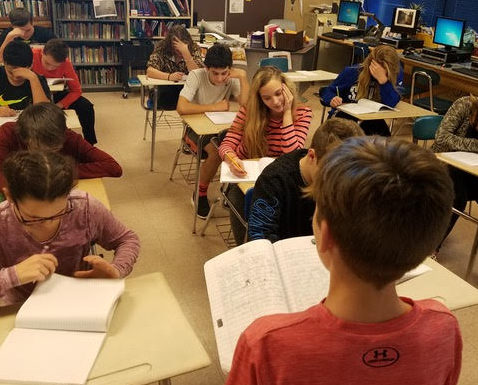

The room is a bundle of nerves, like the first day of school all over again.

I am sitting at my computer following a planning period, the late bell has yet to ring, students are hustling to their classrooms, lockers are slamming in the hallways, and when I spin around in my desk chair five kids are lined up with looks of fear on their faces. I raise my eyebrows in anticipation of their questions. Their concerns.

Before they can start, I suddenly wave them away.

“To your seats!” I shout, “Quickly! So much to do, so little time!”

The room is high energy (higher than normal), like static electricity running through the desks. Students who have not spoken since day one are chatting in loud, high-pitched voices. Others ask to be excused to the bathroom and the nurse. Some already have their heads down and ears covered.

The next few moments usually go something like this:

“MR. ROSE, DO WE HAVE TO SHARE OUR WRITING?”

Yes.

“WHHHYYY?” Groan, sigh, hand on heart, looks of terror, eyes closed, heads on desks.

Because it’s an integral part of the…

“I am NOT SHARING!”

“ME NEITHER!”

We are all going to sh—

“I will throw myself out of that WINDOW RIGHT NOW!”

No you won’t. You will be fine.

“YOU ARE NOT READING MINE!”

I will read a small part of every…

“GIVE ME BACK MY WRITING PIECE RIGHT NOW! YOU ARE NOT READING MINE!”

EYES AND EARS UP HERE, PLEASE!

Silence.

My eyes scan the faces.

Sharing our writing is part of the process of teaching writing. We must not forget this. We write to be heard—we never stop thinking about the reader. Without real readers, there can be no real writing. Readers bring writing to life, help it rise up off the page.

That does not make sharing our writing any easier. Writing takes deep thought, lots of time, and mountains of creativity. Writing takes effort, deliberate revision, inner exploration, and honesty. Writing requires re-reading and re-connecting and re-playing and realization.

Most of all, meaningful writing takes courage.

So it’s no wonder the room is electric today, and every share day. It is a wonderful sign. For if students are nervous about sharing, it means that they have tried to create something meaningful, that they took some risk, that they did all (or most of) the things that real writers do.

Oh, and by the way, I feel all these things too, for I am also sharing my writing. A personal narrative that I wrote with the kids during this unit (during lunch, after school, during study hall, and in the wee hours of the morning before the sun came up).

All those things they are feeling right now? I feel them too.

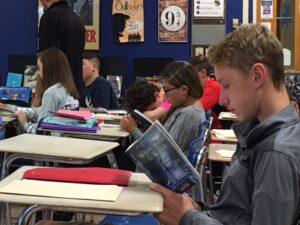

I read my essay first, heart pounding, hands sweaty, voice a little shaky. Students sit and listen, recording memorable words, lines, or phrases into their notebooks. My voice grows steadier with the utterance of each word, but catches a little at the end of my narrative. I clear my throat.

It’s the part of my story where I recollect missing my 6-year-old daughter riding her bike for the first time without training wheels. A moment I promised her I would not miss. A moment I promised myself I would not miss. I had been too busy with my “adult” life to see it happen. I realize this now, more than ever, after writing this piece with the students.

I clear my throat again and read on, and when I look up, glassy-eyed, at the class, they are silent and still.

These are some of my favorite teaching moments, the moments immediately after the reading of our writing, the collective quiet, the breathing, the still reflection, the contemplation, the introspection. We are all in deep thought about the words and the emotions that they stirred. A piece of writing is never more alive than it is in these fleeting seconds after the final word has been spoken.

We have set up our notebooks so that each writer gets a little room for comment, some words of encouragement. Before I can ask for a volunteer, a girl in the front row, Sabrina, has her hand raised. A comment about my writing.

I point at her, afraid to call out her name for fear of breaking the sweet silence. “I like the way you put all of your emotion into it,” Sabrina says.

Another student hand. “It reminds me of when I first rode a bike. The freedom I felt was ex…exhil…”

“Exhilarating,” I finish for him. “I know the feeling.”

Another hand. The room is quiet. “It seemed like you spent a lot of time trying to get the ending just right,” says Ethan. “It seemed pretty much perfect.”

I nod, remembering the early mornings and late nights I had spent trying to create an ending worthy of the words that had come before. An ending that pushed the deeper meaning behind my narrative.

One more hand from student in the back named Kara. “I feel like you would be a good dad. I mean, the fact that you feel guilty for missing this moment is commendable. You messed up, but you owned up too.”

I raise my eyebrows and scan the sea of thirteen-year-old faces before me. Slowly, I put my essay on the bottom of the stack and begin reading the first student essay.

Before I started the read aloud, the students had set up a simple chart in their writing notebooks consisting of three columns: a skinny column on the left side margin for the author’s initials, a second small column for the title of the piece, and then a wider column on the right-hand side of the page for comments, words or phrases, reactions, positive thoughts or feelings evoked from each writing piece. One comment per writing piece. One comment per author.

I had spent the day before talking with my students about how to listen to and respond to writing. I talked about the nerves involved in sharing, the fact that as writers we try so hard to tell the truth, which involves tapping deep emotion and in some cases, reliving the moment. Some of the moments we choose to relive may be painful.

“We are all just beginning,” I remind them. “We are all on the hunt for truth. It can be a messy job. Beginning writing often sounds awkward and new. We must remember that we have all arrived here at different places in our writing lives, and what is most important is that we all grow to be better writers than we were when we first entered this classroom. We all are striving to be more articulate, more able to write in a way that moves the reader. We respect ALL writers in this classroom, no matter where they are in their development as writers. No matter where they might be in their writing lives. We are a community of writers. We stick together. We grow together.”

I begin reading the first student narrative while they listen and record thoughts and feelings. Their life stories are heart-wrenching, full of passion, angst, and wonder. Dana wrote about losing her dog Disney to cancer. Abby wrote about the final moments alongside her grandmother in the hospital. Thomas wrote about getting his nose pierced. Tim wrote about the day at school last year when he was called to the guidance office and told that his father had died. Carrie wrote about her mixed emotions when she moved her childhood doll collection from her room to the attic. Emily wrote about a walk with her best friend named Hannah and the unbreakable bond they share. Stella wrote about a bad haircut and the crushing blow to her ego that ensued. Taylor wrote about not having her father around for the 5th-grade Father Daughter dance. Her grandfather went with her and she had had a wonderful time anyway. Jeremy wrote about shooting his first deer; for him, a day of triumph. Collin wrote about the terror he felt when his sister was lost in an amusement park. Marissa wrote about the day her parents told her they were splitting up. They broke the news to her and her two sisters on the blue, stained couch in the center of the living room.

“They’re our stories. We are the ones living them. It’s our writing. It should be read by us.”

I read them all, slowly and surely, with as much emotion and articulation as I can muster. When I read Marissa’s, she begins to tear up in the front row. I read them because I know (from experience) that brand new 8th-graders may not be ready at this point in the year to stand up and read their own writing in front of 23 other students. I read them because the stories deserve to be heard. When I am done, I look up and see that they are all staring back. Some of them are dabbing at their eyes with tissues.

I wait. Savoring the moments after the final word has been read.

“I want you to write one more comment,” I say after a few moments. “Tell me how this felt, to have your writing shared, loud and clear. Write about what you heard. Did the writing surprise you? What did you hear that you liked? What do you think about all of the writing? How did it affect you? What was good about this writing?”

I invite them to reflect on the experience of listening to everything they have heard.

I read through their notebooks later, long after the final bell of the day has rung. Their reflections never cease to amaze me—young writers finding their voice. Jack says he “learned more about his classmates through this one writing unit than he has in all the other grades and assignments combined.” Sarah says she “liked the way Mr. Rose read her story. It sounded powerful and full of emotion.” Brad wrote that he “liked listening to his own narrative being read, but that the best part was hearing all the different funny and sad and amazing stories of his classmates. [He] never knew that his friends had such interesting lives!” Leslie wants to hear “more narratives from her friends in other classes,” and Bobbi wants “to write more life stories in order to find the deeper meaning behind the memories.”

The comments go on and on and I read late into the evening. Then I read one comment that stops me in my tracks. It comes from the notebook of Charlene, a quiet student who reflected on the memoir writing unit:

“I did not realize that writing could help a person uncover deeper truths about their own life. Writing about the day my mom and I dropped my sister off at college helped me process our relationship as sisters, what it meant to me to have her in my life (and now not). Writing about this important moment made me realize writing, REAL writing is much more than writing about a story that I have just read or writing in response to some test questions. Real writing takes time and energy and deep thought about complex feelings and emotions. Real writing hits the reader hard. Real writing can change minds and lives.”

Charlene does, however, have one major complaint about the sharing experience. She says that Mr. Rose “read it all wrong. His inflection was on the wrong words and he pronounced my sister’s name incorrectly.” Other students have similar complaints. That I did not read their piece “the way that it was supposed to be read.”

In class the next day, I respond to Charlene’s note. I ask students if they would prefer to read their essays in their own voice.

Charlene raises her hand.

“It’s not that you didn’t do a good job, Mr. Rose,” Charlene says carefully. “It’s just that, we know ourselves better than you do.” Charlene suddenly looks apologetic, “No offense, Mr. Rose.” Another student who rarely speaks out in class says loud enough for all to hear, “They’re our stories. We are the ones living them. It’s our writing. It should be read by us.”

“I agree.” Another student adds. “People should hear our voices.”

I smile.

I don’t say a word.

Because, really, there is nothing more for me to say.

Photos courtesy of the author

Daniel Rose is a three-time parent, 17-year language arts instructor, and lover of words and books. Daniel writes with and for his students and has been lucky enough to have his work published by Voices from the Middle magazine, Parent CO, Mamalode, The Good Men Project, and Eureka Street. Daniel lives (and teaches) in Oswego, New York.