Adapted from Journal of a Living Experiment edited by Phillip Lopate, published originally at The Best American Poetry.

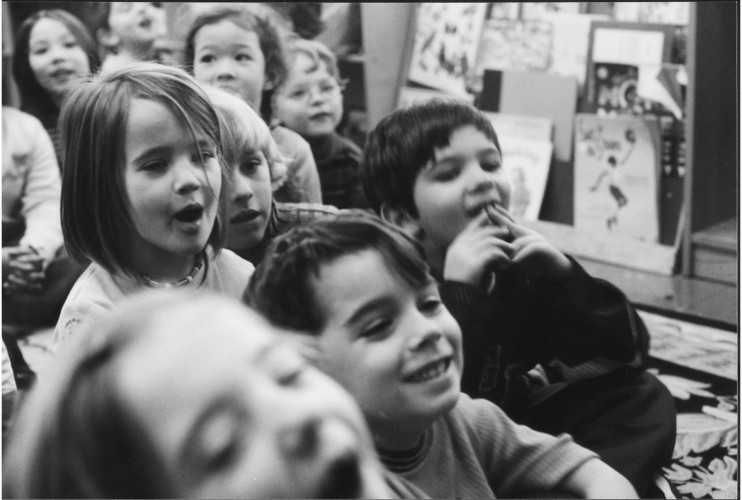

In my first few years teaching I conducted creative writing workshops—with students ranging from six to eighty years old—in public schools (including my former elementary and high schools), community libraries, colleges, P.T.A. meetings, and senior citizens centers, in the five boroughs and beyond. I had one-shot sessions with groups as large as sixty students, and met once a week with a single student for a school year. Most of my workshops were sponsored by Teachers & Writers Collaborative, N.Y. Poets in the Schools, and Poets & Writers, but I also did sessions for groups with names like Young Visitors and Sub Sub.

If it’s Tuesday it must be Yonkers because Wednesday is Lynbrook and Thursday is Spring Valley. A well-kept (and consulted) appointment book became essential. One morning I got a call from the Ardsley Library. “Oh hi, I’m looking forward to seeing you next week,” I said. “There are thirty children here who were looking forward to seeing you a half hour ago,” was the cold response.

I had to be careful with the amount of work I took, to allow time for writing. The idea is for writers to preach what they practice, not what they used to practice. I could not make a living writing poems, but I could support myself helping others write poems. Some of our students would likely wind up teaching others to write, who would then, etc., resulting in an exponential growth in creative writers. One night, overscheduled and underwritten, I imagined a grant proposal to deprogram former students: “You’re upset or rapturous with joy? Pick up the damn phone!” (I also facetiously proposed prenatal workshops, but it turned out I wasn’t too far off on that one.)

I wasn’t making a fortune, but I was fortunate. Teaching was not at conflict with art but in itself an art form. In both writing and teaching, you can alternate between having control, relinquishing control, and sharing equally; it is the wise writer or teacher who knows when it is appropriate to be in charge or to let things happen. Usually the teaching fed into and out of my writing. The same creative energy that fueled my writing also contributed to my teaching. I must constantly find ways for students to make it new, make it real, and make it finished. Instead of struggling with the development of one poem (my own), I sometimes felt like a chess whiz scampering from writer to writer helping each make a move. It was exhilarating.

I experienced the same kinds of ups and downs in my teaching as I did in my writing. Sometimes I was on and the room seemed to glow with energy. In discussing exemplary texts, I almost always taught myself something new. Other times I was off and had to draw on professionalism to complete the task. There were moments when I was exhausted with language, indifferent to imagery, and I felt like Sartre’s bad-faith café waiter, playing the role of writing teacher. But good things often came out of such bad faith, and I had much more confidence as a teacher when I realized I didn’t always have to feel fine to do fine work.

I didn’t plan to be a teacher of creative writing any more than I planned to be a creative writer. I arrived at each from chance opportunities that acted as catalysts for desire, determination, and talent. I wasn’t the kind of child who had a treasure chest of special books; I didn’t sneak into a corner after dinner and write poetry or my autobiography. My first fling with writing came in fifth grade because I couldn’t sing—or so the music teacher determined. He selected all but five of the kids in my class to be in the chorus. My teacher, perhaps in order to soften the blow, made us the newspaper staff.

My attempts at creative writing were mostly confined to song lyrics until the spring of my senior year in college (1970), when I began writing fragmentary poems (influenced by Richard Brautigan) during brief respites from anti-war and campus protests. Two days after graduation I was a reporter on the Binghamton Evening Press. My newspaper career lasted only a few months. In a scene reminiscent of a “B” newspaper movie, a senior editor advised me to “be a writer” while I was young and could deal with insecurities and frustrations. He pointed to an aging colleague and said, “He waited too long before he quit. Came back with his tail between his legs.”

I moved back to New York City, thinking I would write in-depth, novelistic, investigatory, sensitive journalism. A friend told me of an ad in the Village Voice for a poetry workshop conducted by David Ignatow at the 92nd St. Y. You had to send in six poems; 12 people would be selected. I had harbored secret “poet” fantasies, and I thought that the workshop could help my prose writing, so I sent in six of my little poems. I was accepted into the workshop, and my life changed. Journalism stepped into the back seat, and poetry got behind the wheel.

This is over-simplified, but I tell it because it was crucial to the attitude I brought into my classes. I was living proof that poets do not belong to a separate breed recognizable in the cradle. For many of us, an encouraging and sympathetic teacher can be of enormous help in our poetic growth. For me, it was David Ignatow in 1971. But who knows? If my fifth grade teacher had decided that those not selected to be in the chorus could work with a visiting poet I might have gotten started much earlier. So, when I went into a classroom, it was with the belief that anyone could connect with creative expression and invention.

My beginning as a teacher was also partly a matter of circumstance. I had heard of people who taught poetry writing to children, but I had never worked with kids in any capacity and thought that I would need special training to attempt it. One afternoon during the fall of 1973, Stuart Milstein (a graduate school classmate) called and asked me if I could, on short notice, do a few poetry workshops in a Brooklyn elementary school, filling in for someone who had just dropped out of the program Stuart had organized. I was scared, but I said I’d try it. If I screwed up it was Stuart’s fault. Stuart told me that Teachers & Writers Collaborative had some publications that might be of help.

There wasn’t time for me to send away for the books, so I went to the T&W office, which was housed in P.S. 3 in Greenwich Village. Entering the building, I realized I hadn’t been in an elementary school for 16 years. The sounds and smells seemed eerily similar to my old school so many years and miles away, and immediately I felt younger and smaller. I knew T&W’s office was on the fifth floor, but I didn’t know which room. I poked my head into several classrooms before I found someone who pointed me in the right direction. Going up stairways and through halls gave me the deja vu feeling of somehow doing something wrong: going up the down stairs, being in the hallway when you weren’t supposed to. By the time I found the right room, I was having second thoughts about making a reappearance in an elementary school disguised as a teacher. The kids wouldn’t believe it for a second.

The Collaborative office was a classroom with stacks of books, envelopes, and papers. I walked in and shyly introduced myself to a man who was composing a letter. It was the director, Steve Schrader. I told him about the program I was going to be working in and asked him exactly what was Teachers & Writers Collaborative. He set aside his work, gave me a cup of Postum, and talked to me about their work in the schools.

I left the office with a pile of free books and an embryonic feeling of my future within me. My sessions in Brooklyn left me hungry for more. I participated in a T&W-supported training program led by Bill Zavatsky (Bowery Bob Holman was also on the team), and my mother hooked me up with my former elementary school for a series of workshops. I learned as I went along, in front of a class. I submitted an article to the Teachers & Writers Newsletter. It was rejected, but Steve asked me if I would be interested in working in a school in Brooklyn the following fall.

Shop talk appeals to almost everyone; exchanging ideas or just exclaiming and complaining. For most among the new breed of touring writers and artists there wasn’t ample opportunity to meet with colleagues. I treasured my association with Teachers & Writers Collaborative because it provided me with a home base inhabited by a professional family. Teachers & Writers offered extended residencies—you become, in effect, an adjunct faculty member—and they published newsletters, books, and anthologies.

Because I had only been writing poetry for a couple of years, and had just a dozen days teaching experience when I was hired by Teachers & Writers, I was particularly nervous about my highly-accomplished new colleagues. Virtually every article I had read in T&W’s publications was articulate and inventive, often displaying vulnerability and uncertainty. This open spirit eased my intimidation somewhat, but it even seemed to me that T&W people were better at being honest than the rest of us.

So, it was accompanied by a classroom of butterflies in my stomach that I went to my first T&W meeting, at the apartment of then-associate director Glenda Adams, in September 1974. I had just begun working for the Collaborative at P.S. 11 in Brooklyn, along with artist Barbara Siegel and novelist Richard Perry. Barbara was also new to T&W, and the two of us sat together on the couch and talked about P.S. 11 while we sneaked glances at the socializing going on around us. Many had not seen each other over the summer, so there were hugs and smiles. It was heartening to see such a close group, and I wondered how long it would take me to feel a part of it. I wanted it to happen right away but knew it had to come naturally. It didn’t take long for someone to notice the new kids. Karen Hubert—whose articles I had particularly liked for their humanity—came over to Barbara and me and said, “I don’t know you two….but I’d like to.”

In January of my first year with T&W, I was asked to do a lengthy piece on the Collaborative for The American Poetry Review. I accepted, partly because it would give me a chance to talk with everyone about their work, speeding up the assimilation process. One by one, each person confirmed feelings of connection to and freedom within T&W. Everyone felt an implicit demand for hard and good work but was secure that each individual determined objectives and strategies. (If you have access to JSTOR, the APR piece can be found here.)

The only discontent I heard was a nostalgia for the conflicts of the late sixties and early seventies, and the notion that perhaps our stability and hominess were at the price of not dealing assertively with social issues. I had an ambivalent reaction to this. I had been active in the student movements of the 60s, and missed talk of lofty goals. But it was also a relief to be involved with a group that didn’t fight within itself, and didn’t have a distorted notion of its capabilities for social change—a group whose ideology is embodied in its daily work.

I was given the room to grow and develop, but I still had to grow and develop. My own creative pride, bordering on stubbornness, was such that I rarely went in with an exercise lifted directly from a book or from another writer, at least not without a twist or variation of my own. Whenever possible, I tried to do things I had conceived myself. (I might later find out that something had been done before, much to my annoyance.) I developed a full bag of teaching tricks, but I tried not to teach by rote—even if it was my own rote. Teaching creativity means teaching creatively. It has less to do with formulas and more to do with human beings and familiarity with such processes as discovery, recall, adaptation, influence, connection, manipulation: the use of language to create, re-create, and, not to be forgotten, recreate. Gradually, my presentations became more complicated, with more possibilities for writing. I had an obsession to type every good piece written by my students, so they wouldn’t vanish like unrecorded jazz improvisations, and I could share them with other students.

I had embarked on a career.