Marty Skoble, who, for the last 42 years has been the recognizable, cheery face of Saint Ann’s School, climbs the stairs two at a time to arrive at his first class of the morning. He’s 77 years old, and not an ounce of time is wasted on recounting his glory days. On this balmy Tuesday morning in Brooklyn Heights, en route to Miss Susie’s second grade, he’s focused on the present.

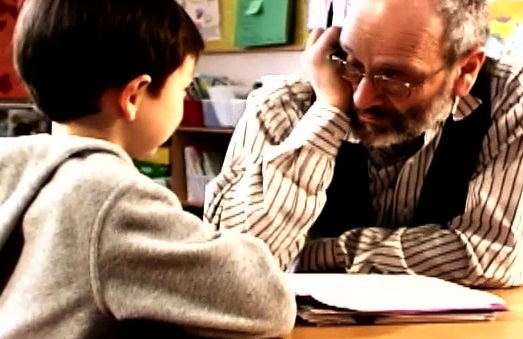

Entering the classroom, Marty, eager for his own lesson to start, pauses to watch the students rehearse for an upcoming performance. A student dressed as a peanut performs a back handspring as her peers erupt in song and dance, which makes Marty crack a smile. When the rehearsal wraps up and Miss Susie instructs her students to help Marty re-position chairs and tables, he is already several beats in front of them, having side conversations with his young onlookers.

“Marty, Marty, are we printing today?” they ask him.

“We’re printing,” he answers with professionalism.

Printing or inking, as Marty sometimes refers to it, is his code word for poems that are ready for final drafting by his students. Over the last few weeks, their poems have been worked and reworked and are now ready for the kiln—aka Marty’s computer—on which he types them and prepares them for binding in books. For every poetry form taught to the lower school grades (kindergarten through third)—be it descriptive, acrostic, lune, diamond, or free verse—a book is created. This year alone saw the printing of 144 books.

“There’s always an excess,” Marty explains of the poems that do not make it to the printing stages. “The assumption there is that, hopefully, you’ll try to write a better one.”

In Miss Susie’s room on Tuesday morning, the kids are printing their lunes, a form arrived at by folding a sheet of paper containing four sentences in order to create four new and, sometimes, illogical ones. Words are mismatched, teased out, seized upon.

A student, Carter, reads aloud his syllable lune, boasting of its waywardness: “The Decagon is/ the size of/ the ocean of ham.” His peers laugh and nod encouragingly. “That’s gotta be one tasty ocean,” another student tells him.

At these early stages, Marty is not interested in where ideas come from, only that they can persist. “My philosophy is if you make a kid write the same poem a hundred times, you’ll get the kid to write a perfect poem and he’ll never want to write another one. But if you let him write a hundred poems, one of them will be perfect…and he’ll want to keep writing. When we experts, grown-ups, say that a child doesn’t get it, we usually mean that they don’t get it in the way we want them to get it. I suppose there are children with no imagination, but I haven’t met them.”

***

For someone who has worked at a school for as long as he has, Marty doesn’t wear the look of obsolescence. He types at the computer as effectively as any GenXer. He is as graceful at recalling a Kenneth Koch poem as he is remembering an anecdote from a former student.

Since the 1980s, Marty has held the honor of being Saint Ann’s sole poetry instructor, a distinction he received not because he aggressively applied for it or waited his turn, but because he invented the role. In 1974, he was teaching English part-time at Queensborough Community College when he was invited by his son’s first-grade teacher at Saint Ann’s to come in to teach an early beginner’s poetry workshop. By 1976, he was working in multiple lower school classes, which meant that as the first students got older his contract grew in scope. He went full-time in 1993, with a workload that included elementary, middle, and high school students, and a curriculum entirely of his making.

“It happened because I wasn’t trying to do it. It was not policy at the time to give one subject to one teacher,” he recalls. Marty speaks casually about his origin story, despite how many current and former students credit him with their successes. As it happens, a long career at a storied school like Saint Ann’s means that many literary luminaries have passed through Marty’s office, a room surprisingly tidy given the number of memories collected there over the years.

At the end of the 2017–2018 school year, however, Marty Skoble decided to scale back his hours to just two high school classes a week. Now, his two successors who will start in the 2018–2019 school year, poets Asiya Wadud and Dolapo Demuren, will occupy the halls in the great house he has built. Though Asiya has been employed as a teacher at Saint Ann’s since 2016, her transition to poet-in-residence, along with Oludolapo, marks an important moment in the school’s history—one that potentially demonstrates how poetry-as-instruction is a growing part of its ethos.

***

Whereas the lower school poetry classes are mandatory—making Saint Ann’s a rare breed among schools—the high school class is an elective. It takes place after school and the students, ranging from ninth to twelfth grade and entranced by the upcoming summer break, enter the classroom. Throughout the class, students take bathroom breaks or help themselves to second or third servings of cheese, fruit, and crackers (yes, Marty supplies his students with food) with few distractions to the others. When lodged in their seats, they are either engaged in Marty’s freewheeling affections or busy in thought, grabbing for their own opinions.

There are no grades or special assignments or hard and fast rules, except that each student has to comment at least once during class. Each week, the high schoolers are tasked with writing a new poem as well as openly discussing their peers’ works. Their comments ring with positivity, a cadence rooted in the belief that praise will beget more praise, that the call-and-response of “I like” is evoked via Marty’s own appreciation of the possibilities of language. When choosing to comment on poems, Marty focuses on what works versus what does not, an effect that makes the review process less repressive.

Alumni, many of whom have gone on to make special names for themselves, are keen on remembering this. “I always felt that I would keep writing poetry, in part because I love poetry and in part because I love Marty,” playwright Anna Ziegler says. “A lot of us who became writers became them because of him. He would make you feel like you were a really good writer.” This latter point became an inside joke within her family when her parents teasingly questioned how all of Marty’s comments could be positive. “In a class where he’s nice to everyone,” she adds with a laugh, “you really want to know whose work he likes the best.”

“I only tell them what works,” Marty says. “Maybe occasionally I’ll tell them they don’t need a certain line, but that’s different than saying ‘this doesn’t work,’ or ‘this is a bad metaphor,’ or ‘this doesn’t make sense’.”

That type of criticism may be reserved for MFA programs or residencies, where students may be taught how to write or, more commonly, what to write. For a former student like writer Marc Jaffe, who studied under Marty during his junior and senior years, that openness paid off. “The MFA can lead to situations where you get a lot of negative comments, where you’re effectively sidelined,” he says. To him, the lack of negative commentary in high school produced an environment that was devoid of competition, where everyone was treated with equal deference. “You weren’t just writing poetry. You were a poet.” Ironically, despite the number of Marty’s former students who have gone on to heralded MFA programs, most have come back with stories about pushing back against the rigidity therein, of being able to do so because of the confidence Marty instilled in them.

Such testimonials are not mere coincidence, like a pass-through stage on the way to greater ideals. Girls creator Lena Dunham emailed that her former teacher has “spark, passion, and power. He has a bellow that shakes rooms. He changed my whole life.” Similarly, Alissa Quart, whose new book, Squeezed: Why Our Families Can’t Afford America, comes out in fall 2018 and whose daughter currently attends Saint Ann’s as a first-grader, has described Marty’s teachings as incorporeal. “I remember him offering us cookies in what must have been an after-school writing class, and him closing his eyes when we read our poems like he was listening to, say, jazz. I hadn’t seen that before!”

Meghan O’Rourke, whose career has garnered many major awards, such as a Guggenheim Fellowship and a Lannan Literary award, credits the after-school space with being exploratory while also encouraging one’s confidence for submitting poems to publications. O’Rourke’s first poem was published by Hanging Loose in their high school section. “That publication made a huge difference in my sense of ownership as a person, as a writer,” she says.

Playwright Bess Wohl had Marty as a teacher from first through twelfth grade. “Marty has this way of teaching without teaching you. He folds poetry into your life, into experiences of being alive. Poetry never felt like work.” That may be Marty’s whole point.

After graduation, some of Marty’s students may never write another poem or take another poetry class. They may never share the ideals of some luminaries described above. Nevertheless, they will remember the openness and inclusiveness Marty aspires to; how, even when there’s nothing to say and Marty tells his high schoolers, “There’s nothing much to say about this one. I like it, that’s it.” There’s a wisdom in learning not to be afraid to talk about poetry in sometimes breezy terms. In fact, Marty might revere that possibility. It’s in this space where the connection between elementary and high school learning lives, where Marty might say to both, “Do something silly, see how it comes out. Try something strange. You don’t have to print it.”

***

When Marty talks about the climate his successors are adopting, he is optimistic. Saint Ann’s School does not give grades. Marty Skoble does not believe poetry can be graded. The natural antidote, then, is that if poetry cannot be graded, it can be appreciated. “The emphasis [is] on testing throughout the country,” he says. “The financially expedient thing [would be] to shift [instruction] to something you can measure, rather than something more ephemeral. There is no test for niceness, for insightful responsiveness.”

Hannah Jones, a former Saint Ann’s student and now the coordinator of the National Student Poets Program, shares Marty’s idealism that poetry can be adopted by schools as a core subject. One of her program’s goals is delivering poetry to underserved communities, where access to it can be limited at best. Though Saint Ann’s is in a position of privilege, the simple but effective efficacy of its poetry program can become a model for other schools to follow.

Meanwhile, Ms. Wadud and Mr. Demuren will become, respectively, Asiya and Dolapo, just as Martin Skoble has become simply “Marty.” While their poetry aspirations may not be identical to Marty’s—they both want to increase students’ exposure to international poetry— they share his doctrine that poetry is a communal experience, not to be closed off and isolated.

Outside of the school setting, and stepping into future retirement, Marty will try to address his personal mountain of poems in various draft stages which has accumulated over the years. He will compose and edit in solitude, and then, just as he has done for 40 years, elect to share his genius with the world.

Matthew Daddona is a writer and editor based in Brooklyn whose work has appeared in Fast Company, Outside Magazine, Decider, The Rumpus, Tin House, Guernica, and other outlets.