Originally published in Teachers & Writers Magazine (March-April 2000, Vol. 31, No. 4).

The following are excerpts from a tape recording of the Joshua Ringel Memorial Lecture, which Robert Pinsky gave in April 2000 in Baltimore. This annual lecture is sponsored by Teachers & Writers and the Center for Talented Youth at Johns Hopkins University.

—The Editors

Poetry, like any other art, should begin with a physical attraction. Bodily attachment is primary. That is one reason why everyone who takes a poetry course with me is required to type up with his or her own hands or write out longhand with his or her own fingers an anthology: thirty-five or forty pages of what he or she means by the word “poem” or “poetry.”

This is the single thing I do as a teacher that I consider most valuable. Because it involves the basic elements of bodily action and autonomy, it has wide application. I ask it of graduate students and of freshmen. When my wife taught eighth-graders she asked it of them.

Autonomy is powerful and not invasive. We teachers might do well to take an oath like the Hippocratic promise doctors are said to make: to do no harm. Human society needs school, but alas, it often does do harm. And that is another virtue of this assignment: it doesn’t do harm.

I also consider the personal anthology an extremely stringent, unsentimental assignment, because I am saying to the student: What do you have? The invitation to autonomy is a stringent, though not unfriendly, challenge. The content of the anthology can be anything the compiler considers poetry—nursery rhymes, something your mother read to you, the words to music you danced to in high school—though in practice, students virtually never include pop music lyrics. I won’t criticize the choices, I just ask that you choose something.

The anthologies are self-portraits. Often they’re much more personal and revealing than anything that the students write. And inevitably, we touch up self-portraits, make them flattering or dignified. Transcribing means memorizing the text a phrase at a time, a very close form of attention. Often, a student describes beginning to type something he or she thought was a favorite, finding it boring, and turning to something else that surprisingly appeals. Often, typing a poem for the anthology releases writer’s block, perhaps because one is already in the posture and location associated with writing. In a superstitious way, I sometimes feel that the act of physical homage to the spirit of Dickinson or Yeats leads the muse to smile on the one who performs the humble task. And if someone can’t find thirty-five pages worth paying this menial tribute, perhaps that person is studying the wrong art. The truth is, I have never had that happen.

In a way, this assignment is a descendant of what happened to me when I was young. In my freshman year of college I read Yeats’s “Sailing to Byzantium” and was stunned by it. I typed it up and put it on the wall in the room where I had breakfast. I put it over the toaster where I could stare at it, wondering: how did Yeats do that?

Typing or writing is not the most important physical encounter with the poem, of course. The voice is the most essential bodily medium for this art. It should be common practice from grade school through PhD programs for the teacher to read aloud to the students, and for the students to read aloud to one another. That should be how you start dealing with a poem and probably how you finish as well. This notion of “Did you get it?” or “What was the poet trying to say?”—as though the poet has some terrible speech affliction—seems to stem from a pedagogy that is both naive and bullying. Sometimes one will hear a famous professor reading aloud and realize: this person has perfected the skill of saying things that astonish graduate students, without ever learning how to perceive a poem.

Related to that notion is the misapprehension that you’re supposed to somehow “get” all of the work of art on first encounter. People who love rock music or opera would be severely disappointed if they understood every word entirely on the first hearing. Part of the pleasure is having the meaning gradually penetrate on the second, third—the seventh, eighth, ninth, tenth hearing. In the voice of the professor reading clumsily one can detect only a feeble apprehension of the main, the essential pleasure—in its relative absence, there is only the more trivial pleasure of exercising one’s ingenuity, inspiring most of the students to revulsion, a few to emulation.

If the art is physically appealing, then the audience appreciates the experience of having the meaning gradually appear, as with a food or a person or a sport. It’s as though I’d made you a table or knitted you a sweater or prepared a meal for you, and you said to me, “I see that you made raglan sleeves to suggest informality and used a synthetic yarn but with a nubbiness that combines a kind of modern techno-idea and also a kind of….” That’s nice, but what I, as the maker, really hope is that you would say, “I wore it to a party and everybody told me I looked great. I love the way it feels.” Or “It looks great in the living room,” or “It was delicious.”

Making a work of art is more like giving a party or preparing a meal for somebody than it is like giving people an exam. So when people come to you and say something flattering about a poem—but with that little grieving and inquisitive note that says is this the right answer, as though poetry were a form of exam—you can’t help feeling a little sad.

* * *

The Favorite Poem Project undertakes to make an audio and video archive of 1,000 Americans, each person saying aloud a poem he or she loves and a few sentences about why that particular poem has importance for him or her.

I’ve now received something close to twenty thousand letters, without benefit of any elaborate publicity. Entered into the database by student-intern slaves at Boston University, where I work, these letters are often quite moving to read. I urge everyone here to visit the website at www.favoritepoem.org.

One idea of the Project is to have as wide a range as possible of regional accents, professions, ages, ethnicities, kinds of education. It would be disappointing if all the poems were in English—because there are Americans who love poems in Chinese and Yiddish and Navajo, and certainly in Spanish. And in Persian, Sanskrit—whatever, Korean, Italian. Another idea has been that maybe 10 or 15% of the contributors will be civic figures—not celebrities or show business people, but mayors, governors of states and other political figures, as well as religious, educational, non-profit people: the civic realm.

In April of 1998, we had a favorite poem reading at the White House. The President and Mrs. Clinton each read a poem. Edward James Olmos read at the favorite poem reading in LA a year ago, along with Mayor Tom Riordan. We also had Vietnamese immigrants read poems in Vietnamese. An American Vietnam War veteran read a poem. A quite young Japanese-American boy, so little he stood on a chair to reach the microphone, read a haiku in English and Japanese. Then for good measure, he read Auden’s “What Is Love?”

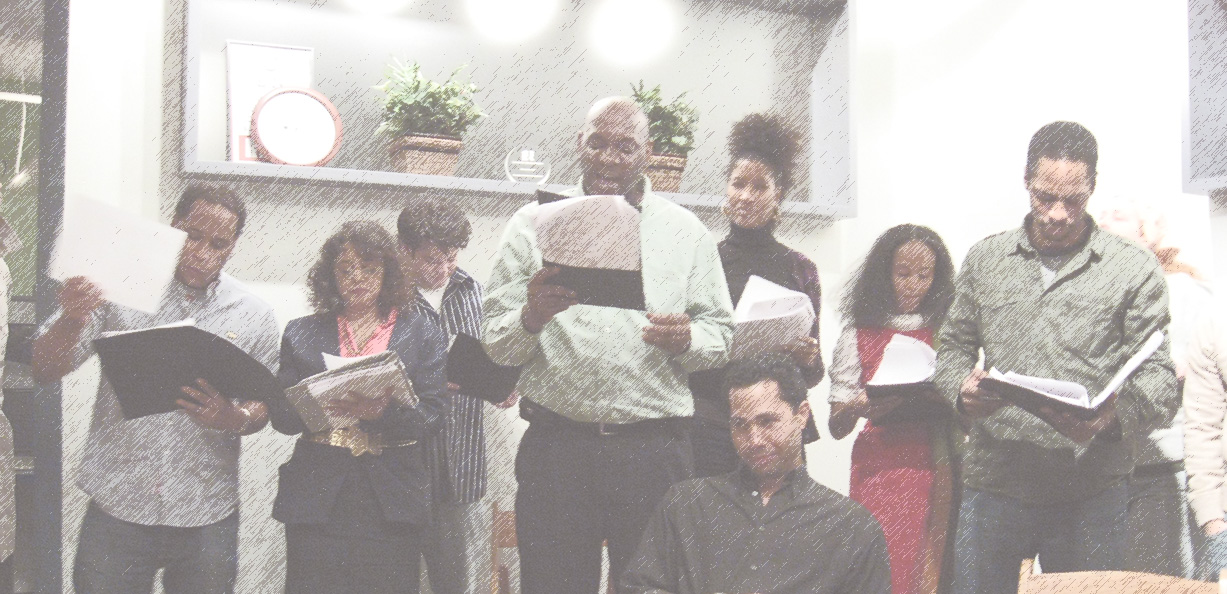

In Iowa the mayor of Des Moines and the governor of the state joined high school students, immigrants, a variety of citizens in reading poems. In Seattle, the fire chief read in uniform. In Atlanta, an African-American postal worker began the event by reading a fiery Amiri Baraka political rap from the early 1970s, an angry poem. He framed it by saying the poem was not exactly what he felt but it represented an important navigational point for him. He sat down to applause and was followed by a woman who read a poem by Anna Akhmatova. This reader related the poem to her grief over her brother’s life, shattered by service in Vietnam. Then an eleven-year-old boy read “Casey at the Bat.” A woman who sits on the Supreme Court of Georgia read Margaret Walker’s “For My People.” An African-American man who writes a gardening column for the Atlanta paper read an Edna St. Vincent Millay poem about spring. A lawyer stood up and recited an Elizabeth Bishop poem by heart. And so forth. I felt I was seeing a portrait of a unity through the works people read.

None of these readers were experts—they shared that and their willingness to read and talk about a poem. They were up on the stage together waiting their turn to read, and you could see them rooting for one another. Afterwards, you could see them animatedly talking to one another. These readings are not only portraits of communities, I believe they are also good for communities. If they’re done right, ideally they don’t happen in a college or university. They happen at a public library. I guarantee you, on the basis of my experience, that if you go to an office building here in Baltimore and ask among the secretarial staff who do the typing and xeroxing and faxing in that building, there’ll be people among them who have poems they love. I. assure you, amongst the managerial staff who work in those offices, there will be people who have poems they love that they’d be willing to read aloud and that they could say something about. The same goes for the custodial staff, the people who wash the bathrooms, clean the floors, and empty the wastebaskets—beyond a doubt, there will be people among them who have poems that they love, that they would be willing to read aloud and discuss in public. And on the boards of directors of the corporations that have offices in the building or that own the building, there will be people who have poems they’re attached to.

Contrary to the stereotype of the United States, there is a readership of poetry. I know this from the Favorite Poem Project. If you look at the list of contributors’ occupations on the website, you will see many teachers, students, and librarians, but also business people, laborers, a ballpark beer vendor, a zoo curator, a circus acrobat. From attending some of the events, I discovered what I had not anticipated: that if you actually went to that hypothetical office building and had a favorite poem reading, it would benefit the atmosphere in the building because the participants and audience would perceive themselves and one another in a somewhat different way.

There have now been many hundreds of these readings, ranging from birthday parties to the one at Town Hall in New York City last week, where American fiction writers read their favorite poems. Joyce Carol Oates read Christopher Smart’s poem about his cat, Jeoffry. Jamaica Kincaid read Wordsworth. Alan Gurganus recited Hardy from memory. Grace Paley read Yeats. And along with the fiction writers, some New York City high school students that Teachers & Writers Collaborative provided read as well, and poems the students selected as well as their remarks and deliveries were very impressive. I’m happy to say that outside Town Hall that night people were scalping tickets to the reading—paid attendance, with about 2500 people rising at the end to give the readers a standing ovation. If you have a reading, be sure to have some kids read. It’s a very good idea to have a preacher or two—preachers understand eloquence, and quote poetry professionally. And if you do it in a school, try to include one of the custodians or crossing guards, as well as the principal and a local politician or two.

* * *

QUESTION: How has your perception of poetry and of language been affected by your work with computers?

PINSKY: My ideas about poetry and about language have been affected by my work with computers. I wrote one of the early text adventures, a product called Mindwheel, that was marketed as an “electronic novel.” I think that project perhaps made me think about the fluidity and speed of poetry, its power to surge from place to place like a speedskater. The work quotes some Renaissance English poetry, and owes a certain amount to Dante. I was interested to note that those elements in

Mindwheel were popular. I’m now poetry editor of the online weekly magazine Slate, published by Microsoft. Each week Slate publishes a poem which readers can hear read aloud, through the speakers of their computer system. These experiences have clarified and deepened my perception of poetry’s strength—its physicality, its human scale, its combination of depth and speed.

In other ways, the interesting thing is how little my perception of language has been affected by my work with computers. Language is language—the word means “tongue-work” I suppose—and its ways of drifting away from the body and back to it again, and many of its other ways, seem to be transposed, rather than transformed, in new media. The computer to me is an artifact that reeks of humanity, as do music and dance and architecture and germ warfare and torturing people by putting electrodes to their genitals, and the heroic couplet and the dyeing of fabrics and the rise of the shopping mall and gene splicing and extravagant American design in the ’50s and ’60s and those super-tiny medical robots that are being developed to crawl around inside our body. All these things smell of us; they’re our works of art. Like language, the digital computer is an extension of our nature.

Working with computers and working on Slate has—like the Favorite Poem Project—intensified my perception that in the context of eternity, these are all equivalent to the dances the bee makes. The different steps in the dance may seem different to us, locally or temporally, but in their essence they’re all very similar.

In relation to that, I’ll read a poem of mine called “The Haunted Ruin.” The haunted ruin of the title refers, as much as anything, to the computer. The thesis is that more or less everything we make or do is a haunted ruin. Body piercing has a history. This language in which I’m addressing you has an extraordinary history—English’s vocabulary is huge, larger than that of French or Italian, because of all of the rape and invasion and expropriation that mongrelized the speech of the island. Each conqueror, having enslaved or raped or terrorized the preceding inhabitants of the island, traded a certain amount of language with the conquered. And the island, therefore, generated this language bizzarely rich in synonyms.

My favorite example of this process is the hill in Cornwall called Torpenhow Hill. A tor, in the language of the Scandinavian raiders, meant a high place. And if the invader asked the invadee or the rapee, “What do you call that?” the answer might be pen in Cornish. The generic name is mistaken for a local place name. So it becomes Tor Pen, which means “hill hill.” But a hough, in Germanic languages, is a rise or elevation. So the place is really called Hillhillhill Hill. And presumably if invaders come from another solar system and conquer us and enslave us, it’ll be Hilhillhillhill Grbzofftu.

The city in Lithuania called Vilna or Vilno or Wilno is palpably haunted. It was once a Polish and Jewish city, culturally. It’s now a Lithuanian city. The place names and street signs and the languages of the shop signs have changed. Most of the Jews—the city was a great center of Jewish culture—were exterminated. Most of the Poles left. That city is obviously haunted, but so, more subtly and invisibly, is this room. If we understood the architecture of this room—if we understood the electronic devices, understood the electric lights, the design and engineering of all these elements, as something separate from ourselves, our presence here—all would be seen as haunted by the presence of the past, and as a ruin because that presence is incomplete, lost.

We get our customary garments and manners from dead people, as well as our language. We don’t eat pig, we eat pork. Because pig is the Germanic language of the conquered and pork is the French language of the conquerors—like veal. We don’t eat calf or pig. You don’t eat cow, you eat boeuf. And those little matters of expression are part of the haunted ruin of consciousness, our partial understanding of where our world originates, far back.

ROBERT PINSKY was the 39th United States Poet Laureate. A professor in the Graduate Writing Program at Boston University, Pinsky is the author of five books of poetry, including The Figured Wheel: New and Collected Poems 1966-1996. He is poetry editor of the online magazine Slate.