Empathy is a central theme in all of the classes I teach, an immeasurably powerful lesson my high school sewing teacher taught me. The ability to pause one’s judgment to see through the eyes of someone else is an exercise in humanity I incorporate into the reading and writing activities of my students regularly, so they, too, may be empowered with empathy.

When I was in high school, I was bullied by students and staff for my romantic preferences, which I didn’t understand then myself. During that time, my grandmother, my best pal, the woman who helped raise me, passed away. I felt so isolated and afraid. But Mrs. Sherwood, my home economics and child development teacher, took me under her wing and taught me about the power of empathy. As a life-long fiction writer, I would retreat to my pen and paper to build worlds and situations that I could control and make as beautiful or as challenging as I pleased. Worlds with brave heroines and heroes who may have been broken in the beginning but always emerged stronger from the monsters they faced. When I had really bad days in high school, days when walking and breathing were difficult tasks to see through, Mrs. Sherwood would tell me, “Sarah, you’re a writer; write.” She told me to write out my hurts and my emotions, to let it all out on the page. Mrs. Sherwood encouraged me to continue what I loved to do, to never give up on my dreams, and to reach for the highest stars regardless of the storms coming my way.

The ability to pause one’s judgment to see through the eyes of someone else is an exercise in humanity I incorporate into the reading and writing activities of my students regularly, so they, too, may be empowered with empathy.

The empathy she continually showed her students, regardless of the bizarre teenage drama we brought her way, may not be quantifiable, but, as an English language arts teacher today, a major part of my pedagogy is based on the lessons she taught me how to show your students care with active listening and encouraging them to pursue their passions.

Mrs. Sherwood greeted all of us as we would enter the classroom with a bright smile on her face. We never knew if she was having a bad day. She emanated nothing but love and kindness to her students with a soft tone and a motherly smile. She took the time to get to know our names and our stories. Mrs. Sherwood would listen to us without interruption or judgment. Once we were done with our tales, she would impart words of wisdom and support that made us feel safe. The understanding she demonstrated of our hurts never felt rehearsed or like an effort to placate. Her kindness was the most genuine and powerful gift many of us students received. I honestly can say, I do not know where I would be or if I would be if it wasn’t for her.

With everything I had endured in high school, my writing had become very dark. Poe and Dickinson were the lights I was trying to reflect. With the sunshine Mrs. Sherwood shone on me and the ever-optimism she shared with all of her students, the themes of my writing began to change. The heroes and heroines were no longer facing the world, they were extending their hands to help one another face challenges together. As an award winning-author today, social justice themes abound in my writing and my antagonists are given opportunities to tell their stories. I often tell my students to ensure that, when they are building their anti-heroes, they’re not just building flat, mustache-twirling, top hat-wearing characters. Even if they don’t write the villain’s backstory into their tales, they need to understand what happened in that character’s life to make them who they are so the main characters may understand how to face their foils.

Building Character

In my ninth and 10th Grade Combination English Class, my students are currently reading my dystopian fantasy novel, The Blue Dragon Society: Origins. The two main characters have relatively parallel backgrounds, but one emerges as a hero while the other descends as the antihero. I created two assignments the students are working on concurrently––one for the protagonist and one for the antagonist. The sheets ask the students to identify what these characters want, what they have at stake, whether they succeed or fail, what we can infer about their personalities and choices based on the clues the author has left about their backgrounds, and the growth or decline these characters make on their journeys. Following this assignment, my students mentioned how they feel sorry for the antagonist, and while they don’t agree with the choices this character makes, they understand the reasons behind the socio-psychological decisions he makes. Having these conversations with my students helps open their eyes and awareness to the sufferings of others, and we continue the conversation with ways we could do things differently if we are ever in a similar position to these antagonists.

As we analyze the characters of other stories, my students develop their own creative writing fiction pieces. To develop their characters, I make my students create character profiles. They have to create stakes, challenges, and backgrounds for their characters to make them well-rounded people whose hurts and weaknesses they understand and can incorporate into the stories they are writing. We regularly talk about how knowing a character’s favorite color of candy isn’t important unless it’s important to the plot. Instead, knowing if their basic human needs were met as a child has a far greater impact on the story and how it translates to our own life experiences.

The Things They Carried

Another activity I use to teach empathy stretches through my A.P. Literature unit on The Things They Carried by Tim O’Brien. When we begin this unit, I enter all of their names and birthdates in a website that tells if they were drafted in 1970 or not. I also collect the draft number that would have been assigned to them in this year. Then, based on their draft numbers, they are called up to pull cards from a pile for their “draft selection.” The cards have names, locations, ages, and a little back story for the characters the students will assume for the rest of the unit. Some are soldiers who ranged from radioman positions to helicopter pilots, some are North Vietnamese citizens and members of the Northern military, some are journalists, and some are anti-war activists. The students research the area their character was from, what opportunities would have been available to them, and they decide, based on the profile they created of their character, what their person would carry with them. Throughout this unit, students write letters to their loved ones describing their current situations, whether in boot camp or at college, and letters from the field describing the situation. They write poems from the perspective of their character, and at the end of this unit, they draw cards to see what happened to their person. As we read The Things They Carried, my students report that they feel connected to the soldiers in the stories in ways they didn’t think they would if they hadn’t been put “in their boots.”

A Meditation

Before creative writing exercises, in my attempt to reflect Mrs. Sherwood’s ways of building a safe place, I do confidence-building activities so my students feel comfortable expressing their opinions or feedback in classroom activities. One of my favorite spirit-boosting exercises is something I start the year or a new semester with. First, I have my students sit at their desk, close their eyes, and start with a deep, long breath in and out. I then lead them through visualization exercises where they envision their best day, their best meal, their best gift, best trip. The basic dialogue goes something like this:

“Picture yourself in the happiest hour on the happiest day of your life. Picture where you were. What can you smell? What can you taste? What can you feel? What do you hear? Who else is there? Can you hear their voice or voices? Hear the laughter. Feel the smiles. Let the lightness you felt in that moment fill you now.”

I usually give them a moment here to take it in. “With that scene still brightly in your mind, whisper to that memory in your heart, ‘Thank you.’ Let that moment, let that gratitude continue to be with you.” While speaking, I quietly set a handwritten note card on their desks with their names at the top and the message, “[Name], you are a smart, powerful, creative being.” After their final moment of taking it all in, I count them out of the meditation, and when they open their eyes, they see the little note I left on their desk.

You are a smart, powerful, creative being.

Following these exercises, I’ve seen my students become more creative and more confident in their academic and social abilities. One student who did not speak in class now regularly starts off our classes playing piano at the front of the room. Her writing ability also increased following these exercises; her writing went from below grade level to being on track over the course of one year. Another student who was also very shy is now seeking leading roles in our school’s theatrical dramas. I’ve done variations of this exercise for a couple of years now, engaging their imaginations, memory, and creativity. I’ve had several students show me that they keep the cards I wrote to them in their wallets, phone cases, or pencil boxes. They’ve told me how much they appreciate these little reminders of their worth.

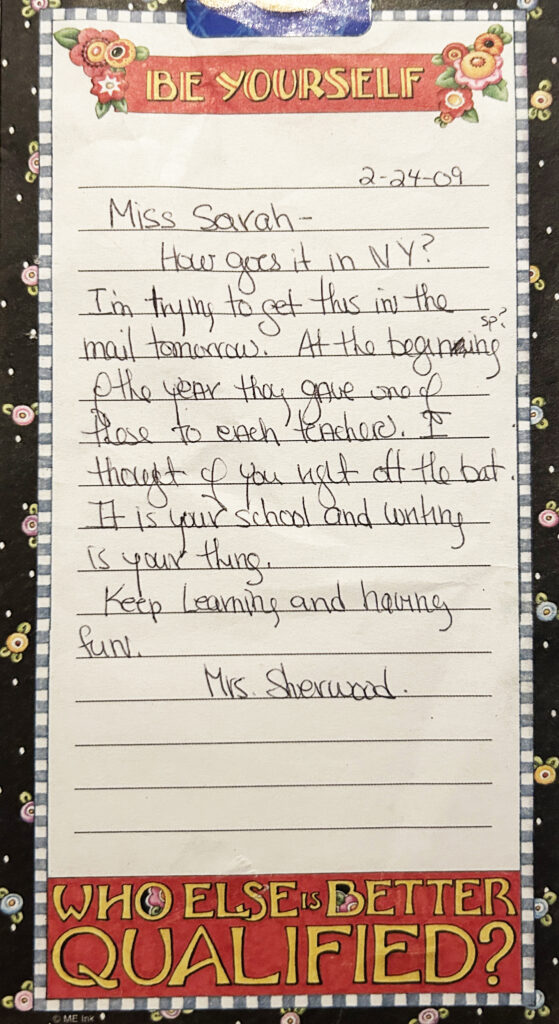

Pursuing Your Thing

Mrs. Sherwood would make efforts like this for us––encouraging notes on papers, stickers, fist pumps in the airs for our victories, little cheers. While these actions did not seem like much in the moment, she was our cheerleader, building up our confidence without us knowing it. I still have a notebook Mrs. Sherwood mailed to me in my first year of college and in the front is a handwritten note from her that says, “Writing is your thing.”

Mrs. Sherwood regularly would tell us about the importance of pursuing our “thing.” That even if we just start digging into whatever challenge we have in our way, it is a tremendous step forward. With the feedback I provide for the activities of my students, I place emphasis on the efforts they are making, on the value of trying even if they do not succeed. That every failure, as much as the victories, are opportunities for growth.

Teaching our students how to use language meaningfully doesn’t just mean showing them how to structure and defend a thesis or showing them the proper placement of a comma. Mrs. Sherwood taught me to look beyond the printed standards by showing our students how to grow into caring and empathetic human beings.

When Mrs. Sherwood passed away a few months ago, it felt like I lost a mom. The ache is still very real and many tears have been shed in the making of this article. One of the last conversations we had was about how proud she was of me for my writing and for being a teacher and how she still wanted me to continue to reach for more. I told her I wanted to be a college professor someday so I could teach future teachers what she taught me. She encouraged me to go for it with a sweet little cheer. At that time, I really hadn’t been sure how I was going to pursue that path, but now it is my mission to see it through so I may continue her legacy of teaching others the power of empathy.

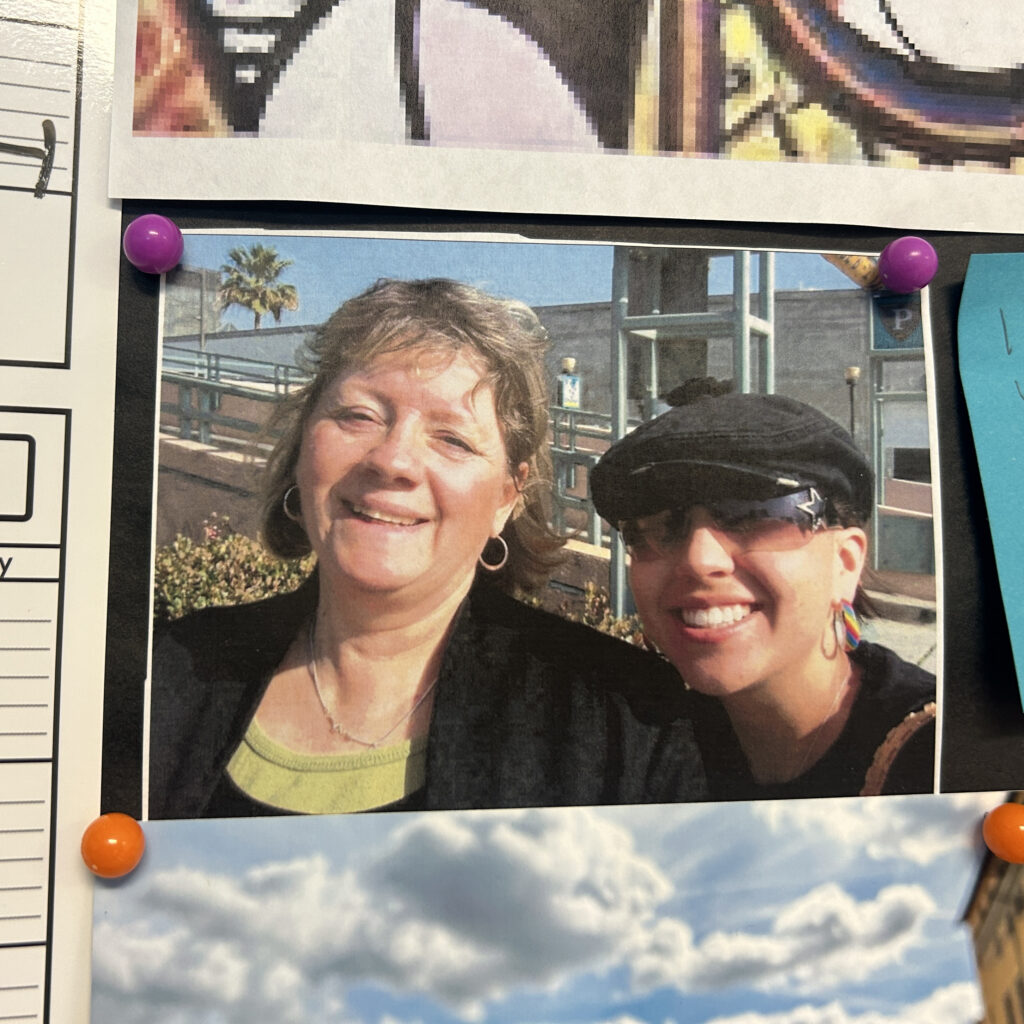

On the board next to my desk at school, I have a photo of Mrs. Sherwood and me on a field trip from way back in 2008. Her smile is my daily reminder to be there for my students the way she always was and continues to be there for me.

Featured photo by Alex Fu.

Sarah Faxon

Sarah Faxon is an award-winning fiction author. On top of writing fantasy, horror, and thriller novels, she teaches English Language Arts and AP Psychology at a creative arts high school. Sarah writes regularly about classroom activities and creative writing on her blog, which may be found at www.sfaxon.com. She loves empowering students and teachers with the tools to succeed, many of which may be found on her Teachers Pay Teachers store.