FROM THE ARCHIVE: This article originally appeared in Teachers & Writers Magazine in Fall 2011

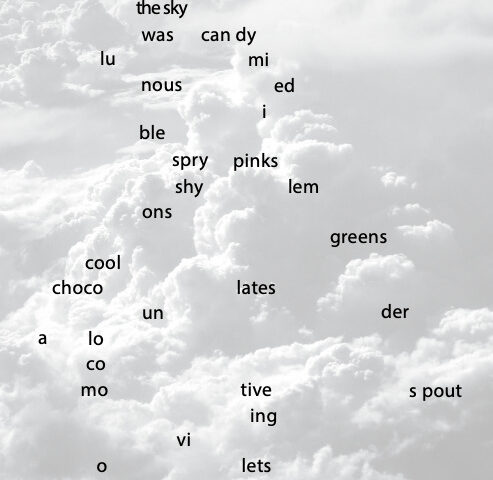

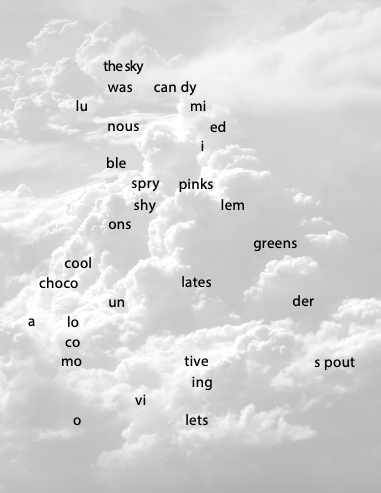

My students at Brooklyn College know that I teach poetry to first-grade students at P.S. 111 in Manhattan—and vice versa. I like to keep them on each others’ radar and occasionally read their new work aloud. The undergraduates are routinely impressed with the kids’ poems; their playfulness and spontaneity is a reminder that poetry can be an adventure. Meanwhile, the first-graders become wide-eyed when I mention that I read their work aloud to the college students. They brighten up like little celebrities. Toward the end of the semester last May, my college class read several E.E. Cummings’ poems closely. One of their favorites begins with the line “the sky was candy.” The poem was a radical departure from everything we had read so far—not so much in content as in form. The students’ initial disorientation led to a series of guesses and discoveries, and mostly they enjoyed the poem’s openness to interpretation. Some argued that the spaces indicate pauses in reading, while other speculated about the poem’s shape. Is it a sky full of clouds, a person on her back looking up at the sky, puffs of smoke from a locomotive? Cummings’ poem brought our attention to the visual quality of poetry on the page, and his division of words into parts highlighted the music of syllables.

“You should teach this poem to your first-graders,” Shamella suggested. I was intrigued.

In ten years as a poet-in-residence in New York City schools, I had never taught E.E. Cummings to kids. The opening line would win their attention, but then the poem becomes increasingly challenging. Words like “edible,” “luminous,” and “spry” would fly over their heads, and the poem’s formal experimentation—words spatially splayed across the page—might disorient young readers learning that words move left to right in straight lines. The nudge I needed arrived three days later, twenty minutes before class. I had e-mailed myself a draft of the first-grade poetry anthology, to be printed at Teachers & Writers on my way to school. The day’s lesson: revision. When I opened the attachment, however, I found a two-page workshop outline. Normally I would pull an old standby out of my sleeve, but it was the fourteenth day of a fifteen-class residency and I had exhausted all of my greatest hits. With eighteen minutes to get from 36th Street to 53rd, I remembered Shamella’s suggestion.

“What color is the sky?” Predictably, several students blurt out “Blue.” “Okay, what color is the sky at night?” This is when the magic kicks in. Aniyah raises her hand and says, “Navy.” Brandon says, “Dark black.” Heads nod. It begins to dawn on all of us that “the sky is blue” isn’t true at all. It depends on the weather and the time of day and the smog and the season.

Without these kinds of accidents, I would rely too long on the tried and true, and teachers know the best lessons sometimes happen spontaneously. Fortunately, we learn to improvise in a pinch: print eighty copies of “the sky was candy.” Run two doors down to Staples and buy a ream of blue paper. Catch the E train to 50th. Scissor-leg to school while hatching a lesson plan. Sign in. Breathe. I write “Sky Poems” on the board, distribute the E.E. Cummings, and read the poem in a big voice— twice. The sky was candy. “What do you call it when you compare two different things and you say one thing is another thing.” Ginaija’s hand shoots up: “Metaphor!” A good beginning. “What do you think the poet is feeling when he compares the sky to candy?” Marc smiles widely: “He wants to eat it.” “Great! And why might the poet want to eat the sky?” I look into a sea of dreamy faces but no raised hands, so I try another angle.

“What color is the sky?” Predictably, several students blurt out “Blue.” “Okay, what color is the sky at night?” This is when the magic kicks in. Aniyah raises her hand and says, “Navy.” Brandon says, “Dark black.” Heads nod. It begins to dawn on all of us that “the sky is blue” isn’t true at all. It depends on the weather and the time of day and the smog and the season. “What color is the sky at sunset?” Here the colors tumble out: red, orange, pink, yellow. My favorite of the day comes from Ayman, who raises his hand with even more sparkle than usual and says, “Peach.” At this point in the residency, the students are confident enough as poets that I can eliminate the structured worksheets I gave them in the beginning. All they really need to get started is a prompt: “In the sky, I see…” I encourage them to use their imaginations—to see something other than birds and clouds and airplanes. For months I’ve been reminding them that “anything can happen in poetry,” so they take these liberties with relish. I also ask them to follow E.E.’s example and play with the way the words dance across the page. Using John Dos Passos’ phrase, I explain that Cummings wanted his poems to provide “excitement for the eye.”

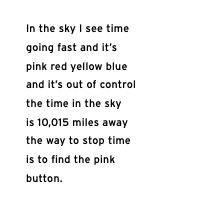

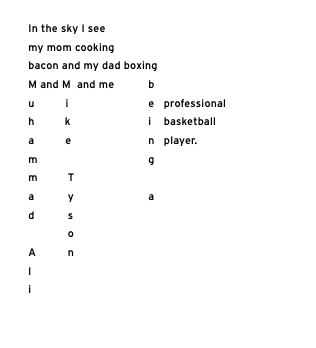

Each student writes a first draft in pencil on unlined white paper. Once they finish, I give them each a colored ballpoint pen (which I had brought for the revision lesson) and a piece of the light-blue paper I am now calling “a slice of sky.” Yes, I am enticing them into writing two drafts using pens and colored paper, and it works. As elementary teachers know, sometimes these touches make a difference. Of course, E.E. deserves credit too. Big words aside, “the sky was candy” is a hit with college students and first-graders alike. And these sky poems are astonishing. Some students connected more with the visionary quality of the assignment. Bryanna wrote her poem in one inspired burst. Her words didn’t shape an elaborate design on the page, but the formal freedom seemed to offer other kinds of permission:

The absence of punctuation in this poem contributes to its headlong momentum, and the final period at the end somehow points to that elusive “button.” I asked Bryanna what she was thinking about when she wrote this poem, and she seemed as surprised with the result as I was. When she read it aloud, the class was similarly captivated—the applause was big and genuine.

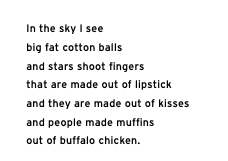

Aniyah’s sky poem is another runaway sentence full of surprises.

All of Aniyah’s poems have this rhythmic internal music that I admire. Alliteration is one of the first poetic devices I teach them, but the internal rhyme of “muffin” and “buffalo” is pure poetic impulse— Aniyah’s ear leading her on in the instant of writing. And it might be the first time in American poetry that “stars shoot fingers / that are made out of lipstick.”

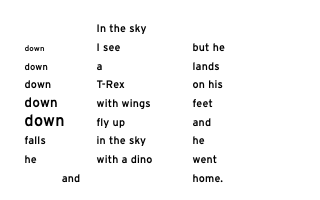

Other students were inspired by the invitation to shape their poem on the page. Travis had a breakthrough with his fantastic sky poem:

Clearly, my concerns about the positioning of text on the page were unnecessary. The E.E. Cummings’ poem issued permission to play and the first-graders ran with it. Edwin often had difficulty focusing on his poems long enough to finish them, but something about the formal possibilities captivated his attention. His sky poem was one of the most structurally inventive of the day.

Like Cummings’ poem, the formal arrangement of the words on the page invites the reader to participate. When Edwin read his poem aloud to me, he began in the central column, read down to “dino” and then up the left column from the bottom (his voice quieting by degrees with every shrinking “down”) and finally around and down the right column. Edwin’s decision to enact the topsy-turvy skyward-earthward movement of the dinosaurs through various textual inversions is brilliant and complex. As you read it you are disoriented at first, but after some experimentation you eventually “land on your feet” like the TRex, similarly exhilarated and rewarded.

Of course, Edwin’s formal gesture was more of an “impulse” than a “decision.” But isn’t that how it works for all of us? We find our way in the process of composition, and our most brilliant moves are usually intuitive. This is one of the reasons why poetry is so important to any writing curriculum: in playing with language, we learn to trust—and enjoy—the process. The magic happens in the act, and the possibilities are limitless.

The following week, I brought the first-grade poems back to Brooklyn College to share with my class. They were blown away, and maybe a little bit jealous. I repeated the exercise with them with some terrific results, but somehow sky-sight came more naturally to the first-grade poets. E.E. Cummings was a poet of childhood who held onto his child-like vision for the rest of his life, and more than one of his poems remind us that the sky is so much more than blue.

who are you, little I

E.E. Cummingswho are you, little I

(five or six years old)

peering from some highwindow;at the gold

of November sunset

(and feeling:that if day

has to become nightthis is a beautiful way)

Matthew Burgess is an Associate Professor at Brooklyn College. He is the author of eight children's books, most recently The Red Tin Box (Chronicle) and Sylvester’s Letter (ELB). Matthew has edited an anthology of visual art and writing titled Dream Closet: Meditations on Childhood Space (Secretary Press), as well as a collection of essays titled Spellbound: The Art of Teaching Poetry (T&W). More books are forthcoming, including: As Edward Imagined: A Story of Edward Gorey (Knopf, 2024), Words With Wings & Magic Things (Tundra, 2025), and Fireworks (Harper Collins, 2024). A poet-in-residence in New York City public schools since 2001, Matthew serves as a contributing editor of Teachers & Writers Magazine.