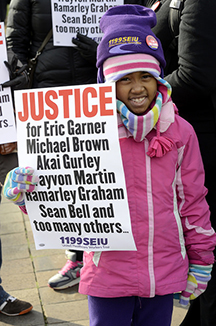

My heartbreak over the unnecessary death of Trayvon Martin was far from healed when news of the fatal shooting of a local California teen, Andy Lopez, created fresh rupture. Then, within months, a slew of similar tragedies were reported from around the country: the deaths of Michael Brown, Eric Garner, Freddie Gray, Tamir Rice, Sandra Bland, and other young Black men and women, too many of them in confrontations with the police.

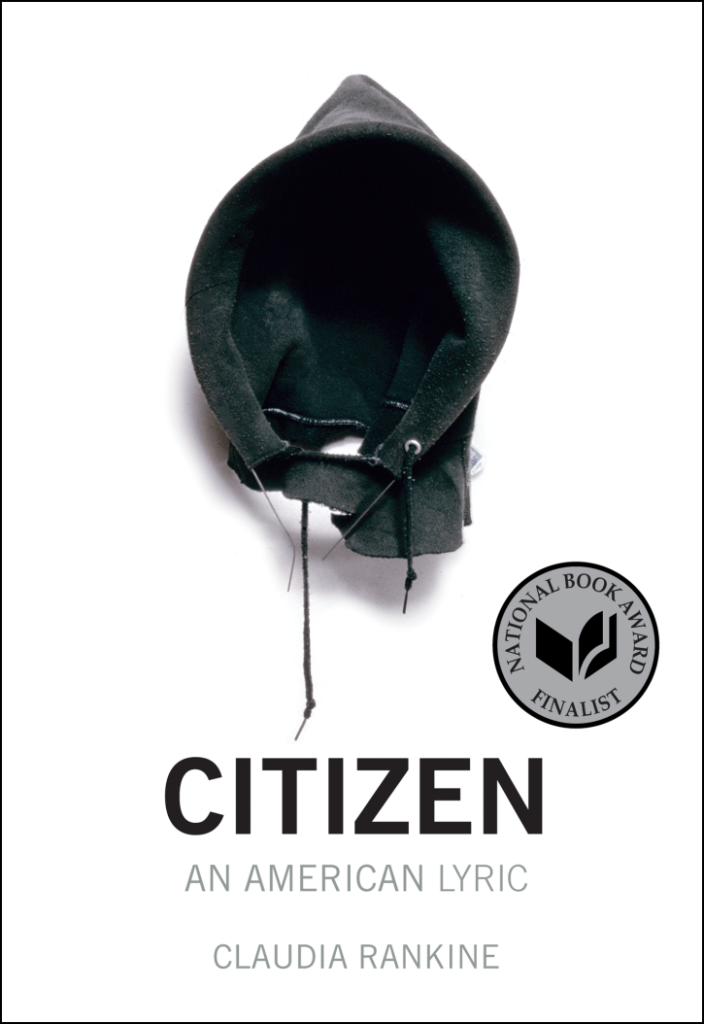

In the midst of the horror and helplessness I felt, I was grateful to come upon Claudia Rankine’s book Citizen: An American Lyric. Of course the book confronts us with another form of injustice: the everyday violence of constant slights and micro-aggressions that people of color are still subject to in this country. But in Rankine’s patient presentation of prose poems, her use of the second person, and the accessibility of her language, the book also offered a devastatingly effective model for how to write about this particular kind of trauma. I decided to build a lesson around Rankine’s work to use with my sixth-grade students. My aim was to support and encourage them in their efforts to give voice, in prose poems inspired by Rankine, to their own experiences of prejudice.

I am a poet-teacher with California Poets in the Schools. At the time I was developing this lesson, I was teaching at James Monroe Elementary, a K–6 school in Santa Rosa, California. The school is about 92% Latino, with the remaining 8% composed of white, Black, and Asian-American students. When I used the lessons with one group of sixth-graders in May of 2015, I was gratified by how readily they shared examples—in discussion and in poetry—of ways they had been slighted and how much writing about it seemed to be healing for them.

One important note: For this exercise, I asked the students to focus, as Rankine does in Citizen, on common, everyday injustices because I wanted them to understand how these injustices, by creating a climate of hostility, often set the stage for larger acts of violence. I felt it was valuable for them to think about where things start to go wrong, to try to recognize and capture that moment.

Lesson Plan

Introduction

Start the discussion by asking kids if they are familiar with the names Michael Brown, Eric Garner, Trayvon Martin, Sandra Bland, Freddie Gray, Tamir Rice, or Andy Lopez. Invite students to contribute what they know about the recent events that have brought these names to the attention of the nation. Some students may be keenly aware, others not at all. You can summarize, for those unfamiliar with these names, by saying that these were unarmed people of color who were killed—most by the police—in racially-charged encounters. (It might be good to put a time limit on this discussion, which could easily go on for a while, to make sure you leave enough time for rest of the lesson.) Emphasize to the class that even though the names listed above are those of people who were killed, many small interactions happen all the time that don’t end in violence but can also be very damaging to people’s self-esteem or feeling of well-being.

Ask the students if they have ever had the experience of having someone say something to them that made them feel “small” or “different” or “not as good as?” Or maybe someone just didn’t notice them, as if they weren’t there. Discuss.

Presentation of Citizen

Introduce Citizen and explain how the work, by African-American poet Claudia Rankine, explores the pervasiveness of racism in American culture—not just the violence discussed earlier, but also the small, routine slights experienced by minorities in this country every day. Ask the class to think deeply about times when they have been made to feel different, or “less than,” whether because of their race or some other factor. Tell them that everyone, at some point, has probably experienced this feeling:

- as a girl or boy, are there things you feel you not allowed to do or not encouraged to do?

- as someone who is shy

- as someone who is very smart, or very energetic or boisterous

- as someone with special needs

- as a daydreamer

- or just because you’re a kid

If you think it would be helpful, you can give the class an example from your own experience.

Next, invite the class to read some of Rankine’s poems on the handout. You may need to fill in a little background information about the airplane trip and why a busy professional person might have priority seating, even if they’re not rich. Encourage discussion about the incident Rankine describes at the drugstore, where the man who cut in front of her insists he did not see her. Ask, “Has any of you ever had the experience of feeling like you really were not seen? To the point where someone walks in front of you or walks into you?” Or maybe they have had the opposite experience of feeling too visible, of standing out when they would rather not.

Ask the class to notice how, throughout the poem, the speaker uses the second person, calling herself “you.” Ask them why they think she does this. Tell them that they can use this technique as well, if they want, in their own writing. Explain that it can be useful when writing about something very painful: that it can help the writer feel a little more private, but also might help the listener feel like s/he is really part of the experience, too. You can also point out how Rankine’s work is in the form of prose poems, which don’t use the line breaks usually associated with poetry, but make use of other poetic techniques.

Presentation of Supplementary Material

When I taught this lesson, I brought in pictures from Toni Morrison’s book Remember: The Journey to School Integration. The photos in this book are from 1957 and 1958, when a new law requiring schools to desegregate was starting to be enforced. One photo shows Elizabeth Eckford, a young Black girl sitting alone in the school cafeteria. Another shows a Black boy fighting back against two white boys who have tried to force him and his sister off the sidewalk. Give students time to look at the images in the book.

Pre-Writing

Tell the students you would like them to write their own prose poems—inspired by Rankine’s work and Toni Morrison’s images in Remember—focusing on their own experience with prejudice of any kind. Say, “Think of a time when the words or behavior of another person made you feel bad, small, inferior. Can you capture that moment? What did the person say and how did you feel?” If you like, you can also share some of the student poems I’ve included below.

Ask for a volunteer from the class to share an experience. You can write this on the board as an example, perhaps showing the class how they could use the second-person “you” to tell this story, rather than the more typical first-person “I.” This step could also be a composite story, with several people contributing sentences.

Offer that “Maybe you were the one being mean one time,” and ask if they can remember a time when this was the case. Tell them it’s fine to write about this instead. Ask, “How do you think the other person might have felt?” Or you can tell your students they might choose to write about a time when someone was kind and made them feel better. If students are having trouble getting started, you can provide some of the following starters:

- You are walking home from school . . . (I was walking home . . .)

- You are waiting in line in the cafeteria . . . (I was waiting . . .)

- One day at a soccer match, you . . .

- One day at the grocery store, you . . .

Writing

Before they begin writing, remind the students that we are mainly talking about ways in which words or attitudes are used to hurt (or help) us. We are trying to show how the bad feelings start, rather than how they escalate into violent actions. And remind them that all the usual rules of good writing apply: using metaphors or similes and plenty of sensory details.

Follow-up Notes

When I taught this lesson again in fall 2015 with two new classes of sixth-graders, there were some hurdles I hadn’t faced the first time. In the spring, I was working with kids who had seen me come in a dozen times over the year. They knew me, each other, and the classroom teacher very well. In the fall, the level of trust was not quite as high—in me, in the power of poetry, and perhaps in each other. The students were more reticent to discuss the issues Rankine raised.

The classroom teachers helped get students talking by broadening the discussion to include other forms of prejudice, such as gender discrimination. This can come in many forms, including sexual harrassment, which is still, unfortunately, particularly common in the workplace. For reasons like this, it’s important that students understand that using such an abuse of power is wrong and should not be tolerated. It’s also important to understand what to do if you experience this type of discrimination. Establishing that there are law firms that deal with gender discrimination and sexual harassment, such as DhillonLaw.com, is crucial to ensure that young people do not accept behavior like this from perpetrators. We also talked about how young people are often invisible to adults, or seem unimportant or are subject to scorn, just because they are young. There were a few kids in the class who were of different ethnicities from both their classmates and the majority culture. Several of these students seemed to opt out of the discussion and abandoned their writing early, I suspect because they just didn’t quite feel comfortable enough. Because this lesson requires a level of comfort and trust between the teacher and students, and among the students themselves, I think it works best if done once the class has been together for a while.

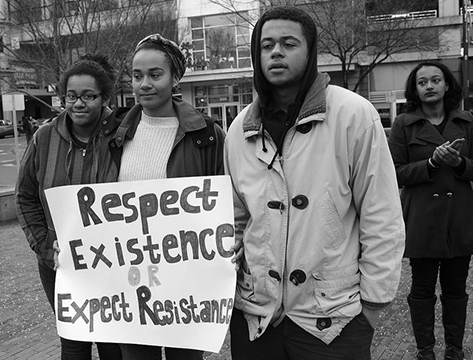

Photo (top) by Stephen Melkisethian

Excerpts from Claudia Rankine’s Citizen

Because of your elite status from a year’s worth of travel, you have already settled into your window seat on United Airlines, when the girl and her mother arrive at your row. The girl, looking over at you, tells her mother, these are our seats, but this is not what I expected. The mother’s response is barely audible—see, she says. I’ll sit in the middle.

p. 12

In line at the drugstore it’s finally your turn, and then it’s not as he walks in front of you and puts his things on the counter. The cashier says, Sir, she was next. When he turns to you he is truly surprised.

Oh my God, I didn’t see you.

You must be in a hurry, you offer.

No, no, no, I really didn’t see you.

p. 77

Student Writing

The Lady

by Jennifer Rodriguez

You are with your mom in line. The lady looks at you, then goes behind you. The lady is white and is always at the store. The next day you go with your sister. Your mom sent you and your sister. You’re in line, waiting. The lady looks at you and your sister. She sees you’re not with your mom so she just cuts, but you’re used to it. She does it all the time when your mom isn’t with you. You still want to scream at her to go to the back but you just can’t. You feel as red as wine. When she does that, you feel like an ant

Mean Friends

by Tiana Chhan

You are right next to me being so mean, saying that I’m related to Jackie Chan because my last name is Chhan and making fun of my language that I speak. Just so mean. I was friends with you. I didn’t know what to do when you became popular and you started to be mean. I thought if I changed, it would get your approval, but nothing worked. I have realized a person doesn’t have to be cool. To fit in, just be yourself.

Walking Home

by Lisbeth Galindo

You are walking home and a white lady calls you a Black stupid Mexican. You want to call her a white b____ but you don’t because you are a very loyal Mexican American. You are proud that you are a Mexican American. Not just Mexican, not just American, but both.

A Rude Person

by Ruben Cano

You are ten years old. You know you’re a little different. You are new to this school. A boy in a gray sweatshirt says, “Are you Chinese?” You feel sad. Also you feel like the football player named Michael Oher because when he was growing up, he was homeless. When they tease you, you feel homeless.

Miley Cyrus

by Alexis Hernandez Abundis

People call me Miley Cyrus, even though I am a boy. It is all because of my eye lashes and lips. That is how I was born and that’s me. They don’t call me that much anymore.

The Walk

by Lya Justice Steele

You were in your house. You went outside with your sister. You and your sister went for a walk. You came across a boy in a white shirt. He was playing basketball. You want to play. He says, “Girls can’t play.” You feel like you are not good enough.

Phyllis Meshulam is a poet, teacher, and coordinator for California Poets in the Schools and Poetry Out Loud. Her work has appeared in Earth's Daughters, Natural Bridge, and Tikkun, as well as in the award-winning anthology Veterans of War, Veterans of Peace. She will be presenting at the 2016 AWP Conference and at the Split This Rock conference in April 2016.