I felt that Ewing’s poem would offer a much needed opportunity to provide context to the countless injustices they had witnessed nearly in real time through images and video, particularly with the death of George Floyd during the early stages of pandemic lockdown. My aim was to help students see that poetry can offer a means of reckoning with history and trauma, and to show them that there is power, and perhaps even beauty, in the process of artistic re-envisioning.

Around my sophomore year of college I joined a Facebook group named something like “Yes, I’m an English major, and no, I don’t want to be a teacher.” Imagine my surprise years later when I was offered a teaching position in my hometown—at my high school alma mater no less. Fine. Anything but middle school. . . . Aside from my own cringe-worthy junior high experience, my reluctance was based on the false belief that the “good stuff”—the most interesting and rigorous texts—could only be taught at the high school level. Yet my current experience teaching middle school creative writing continues to prove just how much I’d underestimated students’ capacity to understand challenging model texts and their ability to identify and adopt the same techniques in their own writing.

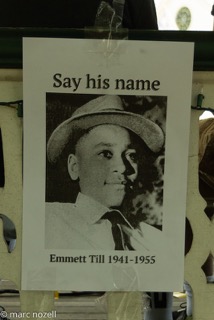

This September I introduced my students to Eve Ewing’s “I saw Emmett Till this week at the grocery store,” a poignantly speculative poem that imagines the 14-year-old boy as a much older man. Ewing’s concrete, fluid imagery allows us not only to imagine Till’s life if he had lived but invokes an afro-futuristic dimension in which he still lives and resides safely among us to enjoy the quiet pleasures of the mundane within the poem forever.

I will admit that I was anxious about how to present a poem about Emmett Till to a middle school audience, especially within the sterile and surreal environment of virtual learning we are stuck with during this pandemic. Nevertheless, I knew there could be no sanitizing the history of Till’s horrific death any more than I could protect my students from the knowledge that racial violence continues to persist in our present world. Tamir Rice was only 12-years old when he was gunned down by police in Cleveland, the same age as many of my students. I felt that Ewing’s poem would offer a much needed opportunity to provide context to the countless injustices they had witnessed nearly in real time through images and video, particularly with the death of George Floyd during the early stages of pandemic lockdown. My aim was to help students see that poetry can offer a means of reckoning with history and trauma, and to show them that there is power, and perhaps even beauty, in the process of artistic re-envisioning.

I knew there could be no sanitizing the history of Till’s horrific death any more than I could protect my students from the knowledge that racial violence continues to persist in our present world.

I began with an exercise on Padlet, a platform which works like a virtual bulletin board, asking them to respond to the following prompt: “If you could meet anyone from history, who would it be? Why? What do you imagine that encounter would be like?” I followed with a brief overview of the history of Emmett Till and the events leading up to his death. I was surprised when one student recognized that Till was featured in Ghost Boys by Jewell Parker Rhodes, which, by coincidence, had been their summer reading assignment.

I read the poem aloud to the class and then gave the students a few moments to read and process the poem on their own. I encouraged them to note the lines they liked, and to think about the specific poetic techniques that created this resonance. They were first silent and contemplative, yet soon the chat section was flooded with comments. The students were surprised that the speaker in the poem was observing Emmett Till in careful meditation upon something as seemingly mundane as plums.

They were impressed with how Ewing was able to evoke the subject of such a tragic event in a manner that—unexpectedly—felt hopeful.

They were impressed with how Ewing was able to evoke the subject of such a tragic event in a manner that—unexpectedly—felt hopeful.

Jordan Muscal, a 7th grader, commented, “The whole poem has this gentle tone to it, from the way Emmett handles the plums carefully to the way the author watches him softly. I think it’s supposed to contradict the violence and hate that lead to his death.” After learning that the woman at the center of the accusation that led to Till’s death later admitted she lied in her testimony, the students talked about how the poem seemed to provide a space where Till could somehow be awarded the everyday pleasures we take for granted.

We then annotated the poem based on its movement and transitions. I asked them to dissect the poem by occurrences, the order in which things happen, taking note of how it pans from image to image like a movie.

Once we’d finished, I introduced them to the instructions for the “What If ?” poem assignment, asking them to write about a chance meeting with the historical figure they’d mentioned earlier in the Padlet exercise. I offered a form that they could use as a guide based on the movement of Ewing’s poem (which more or less matched what they sketched in class) but made sure they understood that they were free to write in any way they felt the poem led them.

8th grade student Sofia Ortega invokes the quiet movement of observation in Ewing’s poem, as well as the inclusion of objects as subtle yet poignant symbols that allude to the history of the poem’s subject.

I saw George Floyd at the park

He was sitting down, eyes cold and head back.

His legs pushing back and forth like a swing set. Every swing he took wassoothing

and looked like the wind was moving the air.

He seemed to be having deep concentrated thoughts. Almost like he was in

a bubble floating high into an empty white box.I called out his name and he picked himself up and turned around the air spinning

off his hat on the ground.

He smiled and placed his packet of cigarettes in his front pocket.

He did a sorta of “bow” and proceeded to walk to me.He was a soft newborn kitten not a dangerous lion

He was cherished by family, not a Harp seal newly born

He was important, not a dandelion in the winter.

Sofia explained that she included the image of the pack of cigarettes to reference the object that would ultimately be associated with Floyd’s demise, just as Ewing’s poem mentions the candy bar Till set out to purchase before his death.

Jordan’s poem follows a trajectory similar to the model text and incorporates metaphors that contain imagery specific to Jordan’s chosen historical figure, the astronaut Sally Ride.

I saw Sally Ride at the dentist’s today

she was standing by the magazine rack,

fingering through an outdated edition of People,

an amused smile playing on her lips

her eyes flit across the page, and I can’t begin to imagine

what’s going on in her mind

she’s a fast moving waterfall; not a boring puddle

she stood in her own world,

as far from Earth and reality as a space shuttle

used to take her

she set the magazine back in its place

and closed her eyes peacefully,

tranquil as a starry night sky

she’s the second before takeoff in this moment;

not the fiery exit of Earth’s atmosphere

laugh marks etched her face and her

calloused hands told stories of intergalactic adventures

I knew her by the jacket

a royal blue fleece with a black collar that would have stood out

anyway in the midst of Houston’s blazing summer

Astronaut Sally Ride was stitched into the right side of the zipper,

and the NASA symbol stood alert next to it

she finally opened her eyes and I

worked up the courage to call her out her name

she looked around for a second, one eyebrow raised inquisitively,

and I shrank into myself

but then her eyes landed on me and wide grin spread across her face

Well if it isn’t my favorite astronaut-in-training

I beamed with pleasure, delighted that I’d been remembered,

and responded how’s Houston treating you?

she gave a little shrug and smiled I didn’t remember all the traffic, that’s for sure

No traffic in space I guess

she laughed at that

A dentist called out my name and I start to walk away

think of me when you go to Mars, okay?

I turned around, but she was already gone

As these poems show, students are capable of handling responsibly curated texts containing challenging themes with both maturity and grace. More urgently, poems like Ewing’s that address difficult contemporary issues offer a model for students, showing them they can be active and aware participants in framing their experiences and responses to the swiftly changing world around them. In the midst of the turmoil of these unprecedented times, poetry can be a vehicle for agency and catharsis, if we allow it to be.

Brittny Ray Crowell earned a BA in English from Spelman College and an MA in English from Texas A&M-Texarkana. Recently, she won the Inprint Donald Barthelme Prize in Poetry and the Lucy Terry Prince Prize, judged by Major Jackson. Her poems have been published or are forthcoming in Frontier, The West Review, Mount Island, Aunt Chloe, Glass Poetry, Cosmonauts Avenue, The Journal, and the anthology Black Lives Have Always Mattered. She is a teaching assistant and PhD candidate in Creative Writing and Literature at the University of Houston and received an Inprint C. Glenn Cambor Fellowship. A secondary educator for thirteen years, she teaches advanced creative writing in Houston, Texas.