I am trying to recall details about the first teacher whose teaching I fell in love with—what was it about him?

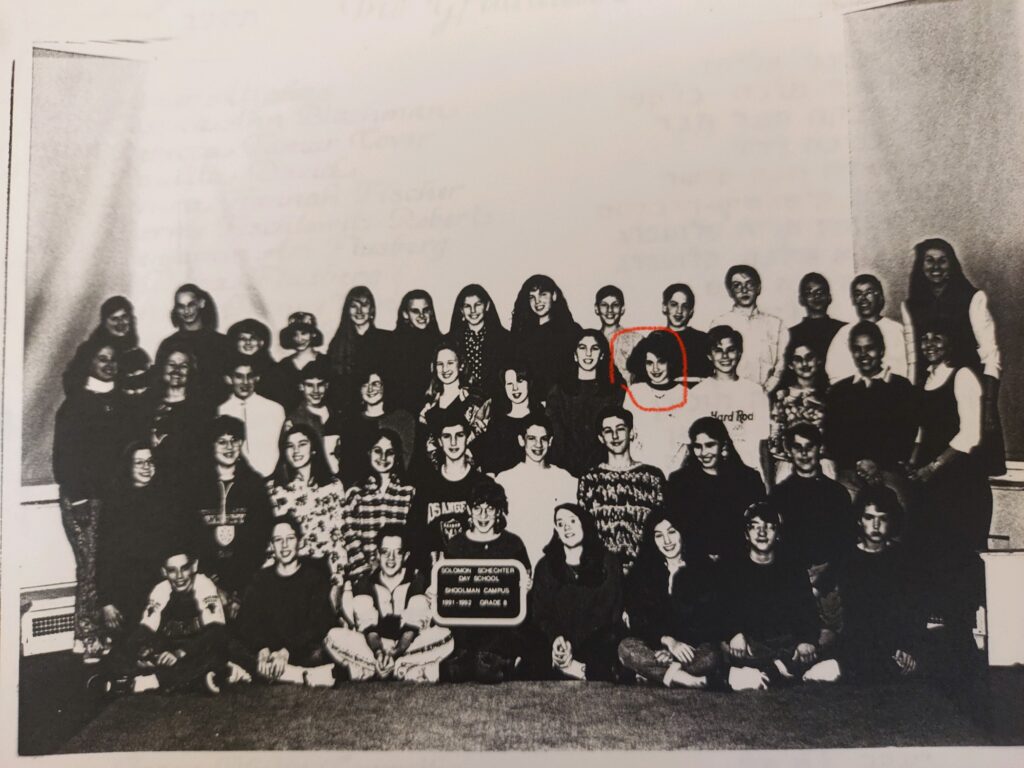

I have strange and scattered memories of Peter Stark’s sixth grade Tanakh class in 1990 at Solomon Schechter Day School, a private Jewish school in Newton, Massachusetts, that I attended from fifth through eighth grade. Generally, I was considered a bad student at Schechter. Teachers called my parents in for talks about my academic performance and disruptive behavior. I often left morning prayers to howl in the bathroom with my friend David or to run through the empty classrooms. I hated the seriousness of Jewish study and embraced the role of class clown if that meant friendship and attention. And even though I was a native and fluent speaker of Hebrew, born to an Israeli mother, I feigned incompetency in Hebrew class and was assigned a tutor who pulled out us remedial students for small-group Hebrew language instruction. We would terrorize that poor tutor, and I have a vague memory of him screaming at us to get back inside as we ran through the soccer field.

I remember Peter as a rebellious teacher. Not the kind to stand on his desk and rally us to action—nothing like Robin Williams in “Dead Poets Society,” rousing his prep school students toward some dramatic liberation. His demeanor was humble and calm, kind of like the Buddha if the Buddha were a round Jewish white man from Freehold, New Jersey.

Peter empowered in me a courageousness of thought. A wildness of thought. My boundary-pushing instinct that drove most of my teachers nuts seemed to be, for Peter, a gift to nurture and grow.

Each class we sat in a circle. Or maybe it just felt like a circle—it’s possible he was at the head of the class. Either way, I got the sense that I was part of a circle. He would tell us mesmerizing and terrifying stories about the Moonies cult, linking the cult leader somehow to the bible. I can’t for the life of me remember the connection he was making. I just remember feeling enthralled by what he was saying, the stories he was telling, and how what he was saying felt really radical and subversive in that context. What did I learn about the Tanakh from Peter? I have no idea.

Peter empowered in me a courageousness of thought. A wildness of thought. My boundary-pushing instinct that drove most of my teachers nuts seemed to be, for Peter, a gift to nurture and grow.

A few days ago, I texted my two closest friends from Schechter, David and Shira. I asked them what they remembered about Peter Stark.

Shira: “I remember the bone above the desk. I remember the end of class when we’d do ‘general smartitude.’ I remember group open book tests. I remember him telling us you could be a good Jew and not believe in god.”

David: “He told me I should be on the new Mickey Mouse club.”

I had forgotten about “general smartitude.” At the end of each class, we could ask Peter anything on any topic, or we could try to stump him on defining a word. Nothing was off limits or out of bounds. Peter was an open book for his students. He was unshaken, ready for any question, any word, any challenge.

In 2006, after completing my MFA in Creative Writing from Sarah Lawrence College, I joined the New York City Teaching Fellows program and taught 10th grade English and, randomly, Economics at a high school in Brownsville, Brooklyn. My favorite class was one that I co-taught with Sidik Fofana, the special education teacher (who happens to be a brilliant writer and author of the book Stories from the Tenants Downstairs). Sidik and I introduced our students to a game called “Stump the Chump” that my sister passed on to me from one of her favorite teachers. For the last 10 minutes of class, students could try to “stump” us on any word in the dictionary. I can’t recall the details, but if someone succeeded, there may have been some prize for the whole class, like extra points on an assignment. Those last 10 minutes of class overflowed with palpable joy. Our students often stumped us with some of the longest words they could find, including medical terms like Pneumonoultramicroscopicsilicovolcanoconiosis. “Stump the Chump” made time and space for unofficial learning to happen on the students’ terms and invited a playfully competitive challenge that we were all in on.

I didn’t make the connection to “general smartitude” until getting Shira’s text. Sidik and I weren’t as brave to open the classroom up for our students to ask us any question on any topic, but I think “Stump the Chump” echoes Peter’s spirit.

I am writing this essay from my parents’ house in Newton, and my mother is working at her computer next to me. I ask her what she remembers about Peter Stark. She looks up and responds immediately. “He formed his own opinions,” she says. “He wasn’t about consensus. He had a sensitivity to exploring and appreciating the individuality of each student.”

The New York City Teaching Fellows program warned against teaching as “the sage on the stage.” They hammered into us the oppressive nature of that approach, which is teacher-led instead of student-led and reeks of the “banking method” of education that Paolo Friere famously critiqued, arguing for a critical pedagogy. Good teaching, we were taught, was about prioritizing what Herbert Moll in 1992 called the “funds of knowledge” of students (the prior, home-grown knowledge they already bring into the classroom) and facilitating opportunities for students to teach each other and become co-constructors of knowledge.

Having been an educator for 17 years, I can say that I wholeheartedly agree that a student-led classroom grounded in critical pedagogy and drawing on student experiences and knowledges is a good thing when it comes to teaching. What I don’t subscribe to, however, are the binaries that this commonsense way of thinking and talking about teaching sets up. Teacher-led vs. student-led. Lecturing vs. co-constructing knowledge. “Depositing” knowledge vs. drawing from “funds of knowledge.” And each way of teaching—whether “oppressive” or “liberatory”—was presented to us as looking a certain way in the classroom.

What does it mean to teach—and to write—in such a way that doesn’t seek consensus, that trusts the validity of one’s own way of thinking, that is sensitive to difference, that respects the wisdom of a teacher or a text, and that recognizes the interdependence of a classroom community for deep study to happen?

Somehow, Peter seamlessly integrated all of those things. He was a “sage on the stage” and he cultivated space for collaborative study and inquiry. He encouraged students’ individual voices and opinions and emphasized collective constructions of knowledge. His classroom was one of both serious study and play. He invited our wild questions and challenges, and he maintained his position as the authority in the classroom. And as much as he resisted conformity to the taken-for-granted notions of Judaism that Schechter seemed to embody, he honored the rules of the school and seemed to very much belong there.

Peter’s non-binary, integrative approach to teaching is one that feels both obvious and difficult to achieve. What does it mean to teach—and to write—in such a way that doesn’t seek consensus, that trusts the validity of one’s own way of thinking, that is sensitive to difference, that respects the wisdom of a teacher or a text, and that recognizes the interdependence of a classroom community for deep study to happen? As educators, how can we be an open book to our students and maintain the integrity of being an authority with structure to make magic in the classroom?

In the fall of 2022, I tried something new with my first-year writing students at Moore College of Art & Design. They were writing artist statements, and I brought in my own statement-in-progress for critique. I joined my students in the circle, providing and receiving constructive criticism. I didn’t think much of this experiment until a student approached me after class and said: “I’ve never had a teacher bring in their own work for students to review. That was awesome. Thank you for doing that.” Though I’ve done in-class writing exercises plenty of times alongside my students (and shared those drafts aloud with them), subjecting my unfinished writing to their critique felt different.

I got the sense that I was part of a circle.

My mother goes on: “Peter genuinely felt that he learns from his students, which is a Jewish value, by the way.”

In 2012, Peter died in a fatal car accident at the age of 62. He was on his way to Schechter to teach that very Tanakh class.

I wonder what bone above his desk Shira was talking about. What question I would ask him now. What word might stump him. What steers the writing of a life. What life. What thought carries on, loops back.

More from this author:

An excerpt from A Poetry Pedagogy for Teachers by by Maya Pindyck and Ruth Vinz

“Reorienting Classroom Literacy Practices: A Conversation with Maya Pindyck”

Maya Pindyck is a poet, interdisciplinary artist, educator, and scholar. Her most recent poetry collection, Impossible Belonging, won the 2021 Philip Levine Prize for Poetry and is forthcoming from Anhinga Press in 2023. In collaboration with Ruth Vinz, Diana Liu, and Ashlynn Wittchow, she co-authored A Poetry Pedagogy for Teachers: Reorienting Classroom Literacy Practices (Bloomsbury, 2022). Pindyck taught in classrooms throughout New York City for over 10 years and earned her PhD in English Education from Teachers College. Currently, she is assistant professor and director of Writing at Moore College of Art & Design in Philadelphia.