For those who have been excluded from educational opportunities, a classroom can seem a forbidding place. Engaging entire families in school-based literacy projects not only supports student learning, but also strengthens the school community. In this lesson, Janet Hurley, co-founder of Asheville Writers in the Schools and Community, describes tweaking the “Where I’m From” lesson—a perennial favorite in creative writing classrooms—to generate collaborative family poems that celebrate students’ heritage and create a learning environment where all feel welcome. Links to teaching materials, student work, and other “Where I’m from” lesson plans are included to support and expand upon the lesson.

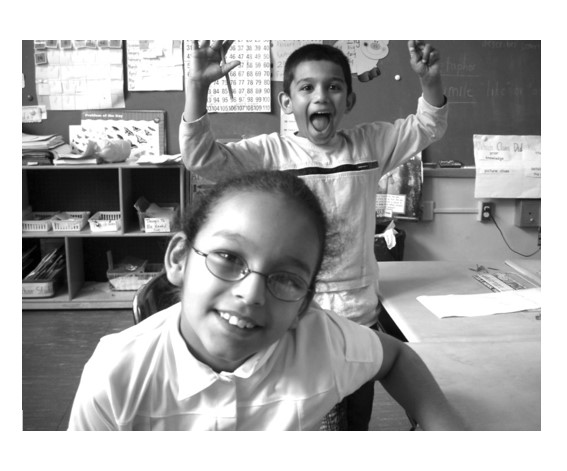

Where I’m From writing exercises have been used in classrooms across the country for many years, but through our Family Voices program we recently tried a new twist on this old favorite, working with third-grade students and their families at Hall Fletcher Elementary School, in Asheville, North Carolina, to create collaborative We Are From poems. For many of the families participating in our program, we recognize that where they are from has meant grave inequities in education and economic opportunity. Our goal is to use this writing exercise not only to honor the history and cultural heritage of those present, but also to make space for the wisdom and voices of families who often feel, or have felt, excluded from school settings. We hope that writing together will build and strengthen their relationship with each other and with the school.

The families participating in our program are white, African American, and Latino, reflecting the demographics of the school. Some of the families from Central America have arrived in Asheville having fled the trauma of civil wars and drug cartel-related violence. School-wide, 70 percent of the students are enrolled in the free and reduced lunch program. School-wide, 70 percent of the students are enrolled in the free and reduced lunch program, and end-of-year third-grade reading tests show many students in the district reading below grade level, with the gap particularly pronounced for African American and Latino students.

Through a series of evening workshops, the Family Voices program offers these children and their parents the opportunity to collaborate in the creative writing process while teachers write alongside and sometimes with the families. To make the program as welcoming as possible, all activities are conducted in both English and Spanish, and participants are also provided with a meal, transportation, and childcare. We divide the participants into two groups, each with a lead and assistant facilitator from Asheville Writers in the Schools and Community. On this particular evening, another teaching artist, Tamiko, and I are sharing the lead and assistant roles.

The paper plates are still on the cafeteria tables when we begin our writing activity, with some of the children and not a few of the parents still crunching on tortilla chips or carrots dipped in ranch dressing. But as Tamiko begins reading George Ella Lyon’s poem, “Where I’m From,” the sounds of eating fall away. I can hear a third-grade boy hush his younger sister and see him lean toward her as Tamiko says, carbon tetrachloride. His brow wrinkles, but he doesn’t ask what the words mean. He knows that, like every evening, we begin by listening to the sounds of words, how they play with each other in a poem, before we dive in to figure out what they mean. He’s eager to take the copy of the poem I then hand out to each participant.

After Tamiko reads the poem, she invites family members to share with each other what they notice or like about the poem and, after a few moments, asks for volunteers to share these observations with everyone. Parents and children raise their hands and Tamiko tries to call upon both in equal numbers. I notice that children tend to like the words they don’t know (carbon tetrachloride, auger, and restoreth), as well as concrete references to food and nature. But when asked if this poem is about where someone lives, I see shaking heads and hear, “No, it’s about family” and, “It’s about memories.” The adults focus on the phrases, “I am from the know- it-alls, and the pass- it-ons, from Perk up! and Pipe down!” and begin to offer their own memories of what they heard in their childhood homes. One woman mentions the poem’s line about “the finger my grandfather lost to the auger,” while another recalls the line about “the eye my father shut to keep his sight.” Others offer similar examples. I then ask, “How did this change things for your family?” and “Do these memories affect you today?” During the responses, I see children looking hard at their parents—some seem surprised, some are nodding their heads as if they already know the answers. This leads right into the next part of the exercise.

I give each family a list of questions and ask them to do a “go round” where each person in their family group gets a chance to talk while everyone else in their group listens. I have the questions written on a flip chart and go through them before we start. It’s more important, I say, to make sure everyone gets to share and be listened to then making it through all of the questions. I ask that each person try hard to be as specific as possible, like the poem, and make it clear that parents/grandparents should talk about the home/place/family they grew up in while the children should talk about where they are growing up right now. Finally, I ask the children to think about how they are also from the memories their parents share. This will become more important later in the activity.

The Questions

What would we notice if we visited your childhood home?

• A town? A neighborhood? A house, an apartment?

- Outside your home,

- What would we see?

- What would we smell?

- What would we taste?

- What would we hear?

- What could we touch?

- Inside your home,

- What would we see?

- What would we smell?

- What would we taste?

- What would we hear? (What are some things your parent or siblings say/said A LOT?)

- What could we touch?

- How did/do people make a living (make money) where you are from?

- In your family (including grandparents and other relatives), what are some of the challenges that people have faced? (In the poem, one person had lost eyesight in one eye, another had lost a finger.)

- What are some first names of your relatives?

- In your family, what are your favorite traditions?

- In your community (neighborhood, school, town) what did /do you celebrate?

As the families dive in to the questions, Tamiko and I circulate to listen, answer questions, and make suggestions. For example, adults as well as children might describe a tree as beautiful. We ask them to close their eyes and remember what type of tree it was, if they knew, and what made it beautiful—the size, the shape, the color etc.

We then ask the families to divvy up the questions they’ve covered, with each member taking two. We hand out previously prepared slips of paper and ask them to answer one question per slip, starting with the phrase We are from….

We demonstrate this on the flip chart, both for clarity and to show how the poetry lines can reference the memories of more than one person, again making the point that memories are part of our heritage. Things can go into a poetry line that aren’t “pretty,” we say, or that don’t seem to go together. We give them an example.

Question: What did you smell in your family home?

We are from the smell of hay and manure and microwave popcorn.

Children too young to write can still participate by having a scribe take down their words. This scribe might be a teaching artist or it might be another member of the family.

Once the slips are written, we ask the families to arrange the lines in an order that feels right to them. We model this on the flip chart with already prepared slips of poetry lines, demonstrating how we read aloud through the lines each time we try a new arrangement and describing what helps us to make decisions—the sounds, the repetition, the sense of opening or closure. “You can take turns with the read-aloud of each arrangement,” I tell the families, “or you might just have each person read his or her own line aloud each time.”

We encourage the third-graders and siblings to let go of any attachment to their line being first or last—something they experience in school all day long from forming lines to go to recess or during testing. We tell them each of the poetry lines has a place and a job to do in the poem and that each is important. On this evening, there isn’t enough time to revise each poetry line, but the exercise still reinforces the concept that revision is about re-envisioning and that everyone’s contributions are important in families and communities.

Once again, we circulate as families consider and rearrange their lines, listening as they read their new arrangements aloud. When they come to their final agreement, which is often surprisingly quick, we give each family a glue stick and piece of poster board and ask someone to take charge of gluing the lines down.

We end the evening by inviting someone from each family to read their “We Are From” poem to their respective group. Mostly, it’s the third-graders who read. Sometimes, though, it’s a parent or grandparent or even a teacher, and all are nervous as they stand up. As on other evenings, though, the attentive listening helps to calm them. I hear chuckles, and see a few nodding heads. In a few minutes, we all head home—but, in this moment, as a community of creative writers, we are all from here.

Janet Hurley is a freelance writer, editor and founding director of True Ink, which provides creative opportunities for young writers in the Asheville, North Carolina area. She is also the co-founder of Asheville Writers in the Schools, a nonprofit which seeks to connect writers with schools and community organizations to nurture confident imaginations, critical literacy skills, and equitable

Hurley has an MFA in creative writing from Lesley College.