Originally published in Teachers & Writers Magazine (Vol. 27, No. 3, 1996).

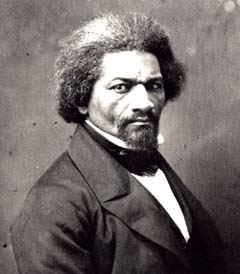

I use any text as an occasion to stimulate students to write meaningfully about their lives, their ideas, and their dreams. I believe that as an educator I must help young people to see and affirm the value of their lives, since so many young people appear confused and unsure about the future. My major objective is to use literature to stir students to write about their own lives so that they might recognize their worth and find more meaningful ways to direct their energies, the way Frederick Douglass did.

Douglass’ autobiography is also an ideal text to explore with students the intersection between literature and history, and to show how a literary text such as Douglass’ is grounded in a specific time. But of greater importance, Douglass’ story reveals how a single person can help change the course of history. Frederick Douglass acted first for his own freedom, but then he didn’t forget his fellow slaves. Instead, he raised his voice in protest against an oppressive system, thereby contributing to its demise.

Before having students read Douglass’ autobiography, I would discuss the value and power of one’s own personal and family history. First, have students make a family tree of living relatives. Next, have students find information about their genealogy, at least three generations in the past, by collecting data from their parents. Recommend to students that they gather more than just names and birthdates. Emphasize that knowing one’s genealogy is important to one’s medical record, as certain health issues, such as sickle-cell anemia and leukemia, are hereditary. Also, specific traits or characteristics or even their names can often be traced to a relative.

Methodology

To provide high school students with vital information about Douglass at a quick glance, without overwhelming them, and to create a lesson for one class period, I read through Frederick Douglass’ Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Written by Himself and marked key paragraphs that I wanted the students to read and discuss. These I xeroxed, cut out, and pasted: twelve excerpts in all, along with some key dates in Douglass’ chronology.

I was a visiting writer at Oakland High School in Judy Yeager’s class and at Burckhalter Elementary in Allison Henderson’s and Nicole Shannon’s classes. In all three classrooms I was greeted by enthusiastic students who readily responded to the lesson.

As soon as the tenth- and eleventh-grade students entered the classroom, I gave each one the xeroxed hand-outs and told them to read through the material silently for ten minutes. When the time was up I wrote “Biography” and “Autobiography” on the chalkboard and discussed these two forms of writing, zeroing in on some of the distinctions between them. We spent some time talking about the idea of “truth,” which many students believed is the advantage of an autobiography. I mentioned how selectivity and intention in autobiography determine the presentation of “truth.” I asked, “Has anyone read an autobiography?” A few students had read Malcolm X’s, Maya Angelou’s, or Maxine Hong Kingston’s. I then asked those students who responded to summarize the impact those works had on their lives and to say what they thought was the primary lesson of each. Our discussion nicely returned me to Douglass’ text. I wrote “slave narrative” and “abolition movement” on the board, then asked students to define both phrases and the relationship between them. I explained that slave narratives served as propaganda for the abolition movement. We talked about the ways a slave narrative could aid the abolition movement. I listed all of their ideas on the board, then framed this question to them:

“Why would the detailed experiences of one slave influence people’s attitude about slavery?” Students offered insightful responses, foremost among which was the elevation of an individual, such as Frederick Douglass, as opposed to a generalized group identity.

At this point I turned to the hand-out I distributed at the beginning of the class and asked, “What do you learn about Douglass at a quick glance from these dates? What is the importance of the dates?” We addressed how dates serve as reference points and provide clues to contemporaneous events. Next I asked for volunteers, each student to read one of the twelve excerpts aloud, and told readers that after reading, they should be prepared to convey the main idea or message Douglass wants to communicate in each paragraph. I also asked them to identify the main emotion in each paragraph. The excerpts, along with their locations in the Penguin edition of Douglass’ Narrative, were:

- I was born in Tuckahoe . . . a slave who could tell of his birthday (ch. 1, p. 47).

- I never saw my mother . . . the proud name of being a kind master (ch. 1, p. 48).

- I have often been utterly astonished . . . the same emotion (ch. 2, p. 58)

- I was seldom whipped . . laid in the gashes (ch. 5, pp. 71-72).

- We were not regularly allowanced . . . and few left the trough satisfied (ch. 5, p. 72).

- Very soon after I went to live with Mr. and Mrs. Auld … discontented and unhappy (ch. 6, p. 78).

- I lived in Master Hugh’s family .. . anyone else (ch. 7, p. 81).

- The plan which I adopted . more valuable bread of knowledge (ch. 7, pp. 82-83).

- We were all ranked together . . . both slave and slaveholder (ch. 8, pp. 89-90).

- In August, 1832, my master attended . .. his slaveholding cruelty (ch. 9, p. 97).

- When we got about half way to St. Michael’s . .. now prepared for any thing (ch. 10, p. 128).

- His answer was, he could do nothing .. . subjected its bearer to frightful liabilities (ch. 10, pp. 133-34).

After the reading and discussion of the paragraphs, I asked, “Has anyone heard of Sojourner Truth? Like Douglass, she was a slave, but she was also a mother and a feminist who advocated the abolition of slavery as well as suffrage for women. Think about the mood and tone of this poem of hers.

Ain’t I a Woman?

That man over there say

a woman needs to be helped into carriages

and lifted over ditches

and to have the best place everywhere.

Nobody ever helped me into carriages

or over mud puddles

or give me a best place …

And ain’t I a woman?

Look at me

Look at my arm!

I have plowed and planted

and gathered into barns

and no man could head me …

And ain’t I a woman?

I could work as much

and eat as much as a man—

when I could get to it—

and bear the lash as well

and ain’t I a woman?

I have born 13 children

and seen most all sold into slavery

and when I cried out with a mother’s grief

none but Jesus heard me …

and ain’t I a woman?

that little man in black there say

a woman can’t have as much rights as a man

cause Christ wasn’t a woman

Where did your Christ come from?

From God and a woman!

Man had nothing to do with him!

If the first woman God ever made

was strong enough to turn the world

upside down, all alone

together women ought to be able to turn it

rightside up again.

“This poem is also autobiographical, as Sojourner Truth uses the personal details of her life as the basis of her argument for women’s right to vote. Reflect on your life for a moment. Are there any similarities to Douglass’? What questions about your heritage do you have? What is your relationship with your parents, or any other significant relative? What are your memories of where you were born? Can you describe a plan or goal you set out to accomplish? Are there things about you that people might misunderstand or misinterpret? Quickly review the hand-out paragraphs from Douglass’ autobiography and select one that speaks to you. Write a poem or a few paragraphs about your life that in some ways reflect either the subject or mood of one of Douglass’ paragraphs. You might want to copy down the first line of the paragraph you choose, so I’ll know which one stimulated your ideas. However, you might want to respond in general to a key sentiment from Douglass’ text.”

Because discussion was so absorbing, only five minutes remained in the period. I requested that students spend at least twenty minutes of quiet, reflective time doing the written assignment for homework and turn it in the next day. Below are some results from tenth-and eleventh-graders:

Question Quest

I’m questioning your morals, your belief and your ideals And yet I need no answer.Now imagine yourself standing on the planes of your limitless

imagination.

Your mind and your soul at ease.

In your life you are always questioned

and with every cause an effect. Every emotion

of yours hangs in the balance and snaps like

a rope around your neck. Imagine the people

you can change with a pencil or a voice speaking

out at a crowd. So stand up and say it and remember

speak loud!!!Imagine the damage you can do to a person who’s as

—Seaton Brook

fragile as a glass, those who hide behind a shell

and remember even stone can crack.

So how do you choose? Do you win or lose in this game we all call life? It is your choice so choose wisely.

UntitledI think education is very important, and because my ancestors had to sneak to learn to read and write, I feel that as a young black person, it is my duty to learn everything I can and that people want to teach me. That’s why I think parents are so hard on their kids.

But what makes me mad are those people who don’t take advantage of what the teacher tries to teach them. I try to learn everything of whatever is being taught. I really believe that is the only way to succeed in life as a black person. Because one thing they were never able to take was our minds.

—Janese Fraser

UntitledEven those who may have sympathized with me were not prepared . . . to do so; for just at that time, the slightest manifestation of humanity toward a colored person was denounced as abolitionism, and that name subjected its bearer to frightful liabilities.

—Frederick DouglassThis sentence has a lot of meaning to me. From my point of view, Frederick Douglass was trying to say a colored person had to be very brave in order to do what he had to do. As a young lady growing up in Oakland, I have to be brave and have a straight head on my shoulders. There are a lot of people around me who are ashamed of themselves, won’t speak their minds and who don’t have much respect for themselves.

I have always felt pretty alone when it comes to speaking out and doing things differently. Since I’m so outspoken, with a lot of charisma, I am sometimes considered conceited. It doesn’t bother me because if I wait for everyone to like me and listen to all the negative things said about me I wouldn’t go anywhere in life.

I can relate to Douglass because he had to make a lot of dangerous statements and take risks by himself based on what he believed was right. I also do the same in my everyday life. If it isn’t standing up for myself, it’s for my friends, peers, family, etc.

No matter how many people didn’t approve or dislike me because of various reasons, it won’t stop me from being me.

—Stacey Reid

UntitledFrederick Douglass knew of only where he was born, he didn’t know the date or what time. He didn’t know much about his family, ancestors, and his people, like me. I only know when I was born. I always wonder where my hometown is. My mom only told me that I was born in China. I always ask her, “Where in China?” but she never answers me. I want to know where it was, how the people are, what they do for a living, etc. There are so many questions, so little answers.

I once heard that I was born on a boat, but I’m not sure if that is true. (Ms. Opal Palmer Adisa talked about “truth.”) I would like to know the truth about my birthplace.

—Yen Phan

“I have been often utterly astonished … “

When my grades have been slippin

or some boy cramps my style

instead of crying like I want

I switch on that radio dial.

The music is my escape

the refuge I create.

When the dishes aren’t washed

and I need to clean my room

I don’t want to crack a smile

I rather wallow in my gloom

so I turn on the radio

and crank up the volume ’cause

music is my escape

the refuge I create.I listen to jazz, R & B and the blues

anything that suits me

and triggers my moodsI feel sorry for myself

or laugh if I choose

the music sometimes

is my only refuge.In the paragraph it said that

—Erika Kremp

slaves would use music, not as

a way to feel happy but as

a way to just feel sorry for

themselves. I sometimes do the

same thing.

There are several activities to engage students in before or after having them write their poems or paragraphs. One such exercise is to have them do a Venn diagram (the type with overlapping areas) to clarify what feelings they have in common with Douglass and where they differ. Another writing idea is to have students list several important dates from Douglass’ life, then establish a chronology of their own lives, cautioning that they should not simply list the mundane things, but focus on specific incidents and episodes in their lives. Suggest that they write at least two sentences for each date at two-year intervals. To broaden this activity students could look up significant historical events that occurred within their lifetimes, and comment on how these events have influenced their lives.

My approach with upper elementary students was similar, except that I tried to integrate more subject areas. Also, because the students were younger and with limited skills, I gave them less information. Rather than twelve paragraphs, I selected five and simplified the chronology.

With these students, the first question I asked was, “What’s one of the most important dates in someone’s life?” As expected, the students responded, “Your birthday!”

“If you were to write about your life, what would you write? What is it called when someone writes about their life? Has anyone ever read an autobiography? Whose? Well, today we’re going to read some parts of Frederick Douglass’ autobiography. Does everyone know who Frederick Douglass is? Let’s look at some dates. When was Frederick Douglass born? How come there is no day listed? Why doesn’t he know the day he was born?”

All of the students in this class, at this predominantly African-American school, had learned about Frederick Douglass the previous year, and in many books for students, Frederick Douglass’ birth is listed as 1817. Two students who remembered this date pointed out that the 1818 date listed in the text I used was incorrect. Also, the encyclopedia in the classroom listed Douglass’ birth as 1817. I suggested that the discrepancy is an indication of the uncertainty about Douglass’ birth, and that recent research indicates that 1818 is the correct year.

I used the chronological information to emphasize to students how important dates are when writing about the events in one’s life: “How old was Douglass when he left the plantation where he was born? How old was he when his mother died? When he escaped slavery? When he wrote his first autobiography? When he died? What are some important dates in your life?” Several students mentioned dates related to their school experience, to moving, or to trips they took with their family.

Then I shifted gears. I wrote “incident” on the board and asked students to define it. Next I gave them a brief overview of Countee Cullen’s poem “Incident.” “This poem was written many years ago by one of the leading poets of the Harlem Renaissance. Has anyone heard of Harlem? Do you know where it is? Harlem is in New York City, and during the 1920s a large number of blacks moved from the South to Harlem, and lots of great artists like Countee Cullen lived and worked in Harlem.” At this point I selected a student to read Cullen’s poem aloud.

Incident

For Eric Walrond

Once riding in Baltimore,

Heart-filled, head-filled with glee,

I saw a Baltimorean

Keep looking straight at me.Now I was eight and very small,

And he was no whit bigger,

And so I smiled, but he poked out

His tongue, and called me, “Nigger.”I saw the whole of Baltimore

From May until December;

Of all the things that happened there

That’s all that I remember.

“What is the poem about? How old is the person, the speaker, in the poem? How do you think the person is feeling? What happened? How long was the boy in Baltimore? What did he do and see in Baltimore? How do you think the boy feels? How would you feel if someone called you ‘out of your name’?” After listing some words that express the boy’s feeling in this poem, we returned to Douglass’ autobiography.

I solicited five volunteers and assigned each to read one of the five paragraphs aloud. We read through all the paragraphs, stopping only to help with pronunciation and explain the meaning of unfamiliar words. After students read the paragraphs, I told them to think of words that express Douglass’ feelings in each paragraph. Students came up with: accomplished, successful, courage, determination, love, unsure, searching, plan, frustrated, outraged, sad, angry, and freedom for the five paragraphs respectively. With regard to the paragraph about Douglass’ mother, I asked students to try to determine the distance from their school to another part of the city that might equal twelve miles, and to imagine walking that distance after a hard day’s work.

Finally I told students to use one of the paragraphs as a point of reference and to write about their own lives, either about when and where they were born, or their relationship with their mother or any relative with whom they have a special relationship, or something they accomplished or want to accomplish, or a memory of being sad and angry, or something they are unsure about. I also encouraged the sixth-grade students to incorporate in their writing one of the words from the list of identification words they came up with for each paragraph. Here are samples from sixth-graders:

Life of Calvin Herring

I was born in Highland Hospital at exactly 12:34 A.M. on April 14, 1984. When I was ten months I had an operation on my stomach. I was in the emergency room for about seven or eight hours.

When I was five some boys were playing fireworks in my father’s greenhouse and two hours later I was in flames and that was the worst day of my father’s life.

When I was ten years of age, I was going to bed, and I was running through the kitchen and I tripped over a computer cord and a drawer was open and I cut my leg. I got seventeen stitches.

—Calvin Herring

A Mother’s LoveA mother’s love is a special

—Larrie Noble

token which can not ever he

broken. One of her loving tears can

open an eye and clean an ear.

Her love cannot he battered

even when it’s almost shattered.

I’ll never forget her love even

her lips as soft as a dove.

I’ll never know how she felt

even when she pulled out

the belt. A mother’s love, A mother’s love

A mother’s love.

How Do You See Me?

How do you see me? Do you look at me as a little black girl living in the world day by day not knowing what’s going to happen to me each step I take?

How do you see me? Do you get scared of me when I pass you walking down the street because I am different than you? Why do you walk away when I ask you a question? All I want is the answer.

How do you see me? Do you even know that I’m there? And when you pass my house in the alley why do you yell such mean things out to me?

—Julie Jones

Determined to Change

When I look outside I see trees. I look the other way and I see violence. When I think of myself I want to accomplish something. I want to graduate and make the world a better place for blacks and everyone else so people could learn to treat blacks like they would treat their best, best friend.

I think if everyone got along the world would be a better place. I see myself in twenty years going to college, making the world a better place.

I still see people outside with discombobulated* minds. I learn you cannot change the world, you have to change the minds.

*A spelling word for the week

—Jasmine Perry

With the fourth-graders, my presentation was similar. Before they began to write I told them that the “I” voice was important, and they should write about themselves, but think about what someone might want to learn about them. I also encouraged them to illustrate their poems or stories or to illustrate a scene from Douglass.

About Me

I was born April 13, 1985. My grandma and grandpa thought I was special and so did my great-grandmother and my mom and dad who took me home. When I was one year old my mom and dad took me to Hawaii and I had lots of fun. My cousin Marcela and my aunty Nora came with us. My aunty is really nice. When I was four I went back to Hawaii. This time my aunty Debbi and uncle Robert came with their three kids. Me and my cousin Rolle were playing and jumping on the bed. That’s all I can remember of when I was little.

—Alia Padaong

Untitled

I feel like I am happy just to be who I am. For many reasons, I am happy. I’m here today. I’m happy because I’m smart learning more and more every day. I have a great teacher to learn from. I’m happy because I’m cared for by a wonderful family. I’m happy because I have a home to live in. I’m happy because I’m happy.

—Veronica Webber

All About When I Was Growing Up

I was born in California and when I was born I went to Disney World. I went to see my cousins and uncles and aunts. They all went to Disney World with me too.

My aunty Dot took me to the ice cream store when I was two, and after we came back from the ice cream store me and my cousins went swimming.

When I was three I knew how to tie my shoes and my aunts and uncles gave me two dollars each.

After I got back to California, I started going to school. When I was five I started going to Burckhalter. I’ve been going to Burckhalter for five years.

—Antonio Perryman

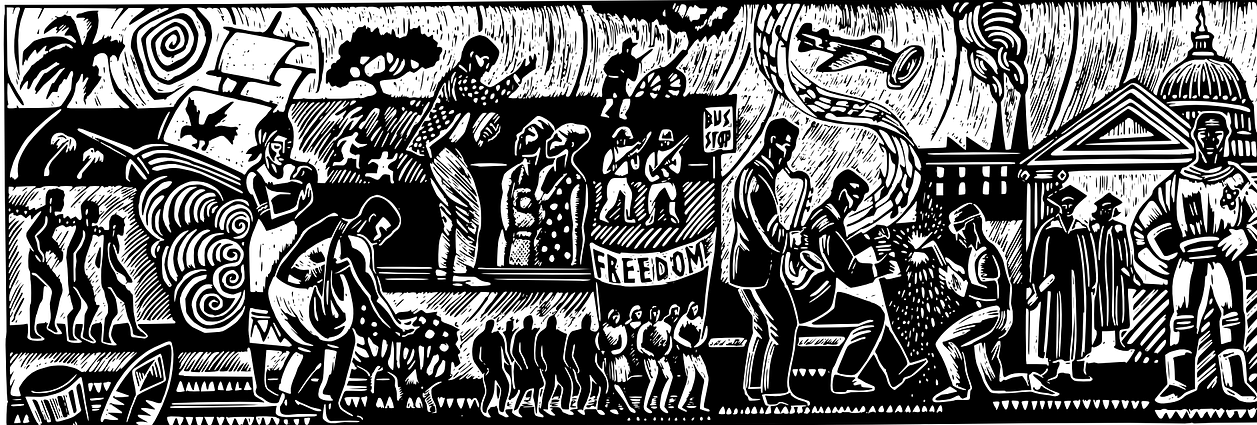

I see these writing exercises as introductions to the reading of Frederick Douglass’ autobiography, and also as a way of engaging students and arousing their interest and desire to learn more about Douglass. It has great value in bridging the gap between history as something that happened in the distant past and students’ own lives. I want students to realize that they are making history, and to think about how they themselves want to be remembered.

Opal Palmer Adisa is a literary critic, writer, storyteller, and associate professor at California College of the Arts. Her books include Tamarind and Mango Women and Pina, the Many-Eyed Fruit.