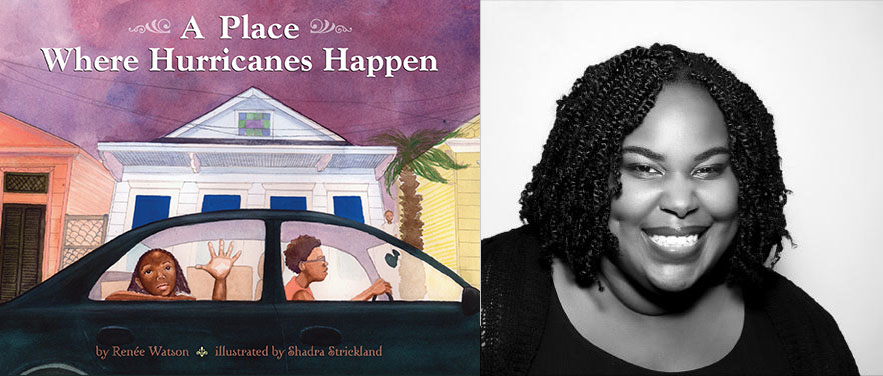

Renée Watson’s books include the YA novels Piecing Me Together, What Momma Left Me, and This Side of Home, which was nominated for the Best Fiction for Young Adults award by the American Library Association. Renée’s writing and teaching work aims to help youth cope with trauma and discuss social issues. Her picture book, A Place Where Hurricanes Happen, is based on poetry workshops she facilitated with children in New Orleans in the wake of Hurricane Katrina.

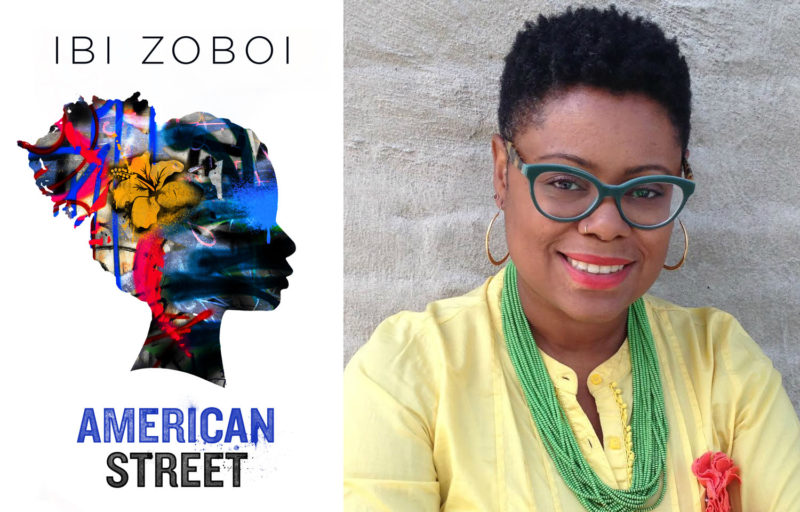

Ibi Zoboi is the debut author of the YA novel American Street, a coming-of-age story infused with magical realism about a Haitian immigrant who comes to Detroit. She has taught creative writing with the Sadie Nash Leadership Project and Teachers & Writers Collaborative, and she designed the Daughters of Anacaona Writing Project, a writing workshop with teenage girls in Port-au-Prince, Haiti. Ibi has also recently completed a teen fantasy novel based on Haitian myth and folklore.

Renée and Ibi sat down in November 2016 with Teachers & Writers Magazine Editorial Associate Maryana L. Vestic to talk about the writers, teachers, and stories that influenced them and how they seek to write, teach, and help young people find not only their inner strength, but their humanity as well. Part 1 of their joint interview is here; part 2 appears below.

Teachers & Writers: What are your particular processes when it comes to helping young people deal with trauma—personal, cultural, global—and what have you taken away from these experiences in New York, New Orleans, Haiti, and Japan? How did your process with students help them find and nurture their own voices?

Ibi Zoboi: I did workshops in Haiti with girls six months after the earthquake. I didn’t have a lot of time there; I had a three-day workshop, but the discussion didn’t center around the earthquake or “woe is me.” We talked about all the things that they loved about their country. We had a whole session on “describe the foods that you love,” and they had to describe it to me and to the reader as if they’ve never tasted it before. It was the most empowering thing that they did. I had them write to outsiders to tell them what a Haitian bouyon tastes like, and all the various Haitian dishes. It was fun; I had them write a letter to their country as if their country was their mother and describe how beautiful she is. We were learning personification, so the tool of expression was joy—to reach in for joy when the trauma is so close.

Working in New York, I don’t know what their personal traumas are. I can’t just assume when I’m going into Brownsville [Brooklyn] that they’re all dealing with trauma. In those instances, it’s just affirming who they are on their page. I find trying to do a superhero lesson plan where they use hyperbole and tall tales empowers them with this craft.

Renée Watson: I think it is crucial to start with joy. I’m just not really interested in mining for traumatic stories because a lot of our funding is for under-resourced neighborhoods, and so there can be an assumption that we’re going to go into these communities and help these young people with their trauma. Lately I’ve been talking to young people about bittersweet moments of your life. What do we want to praise and what do we want to critique and change? You’ve got to have a balance in the classroom. I actually say explicitly, “We’re going to talk about your joy and your pain. We’re going to celebrate, we’re going to find something to praise, we’re going to critique things, ask questions of the world, and make some demands on the world to be a better place.”

I was just in Japan with an international poetry exchange between students at DreamYard in the Bronx and students in Tokyo. I went over to teach poetry workshops and also share my book, A Place Where Hurricanes Happen. It was the five-year anniversary of the earthquake in Japan. Seeing students in Japan write with joy in connection with the questions “What did you love about your home?” and “What are the foods of your culture?” was a beautiful thing. Seeing all these students interact with each other and all these languages spoken in one room was very powerful. For me, like Ibi, I’m excited about my books, but what is most important is being able to engage with the people I write for, talk about things in the book, and have fun.

I tell students that sometimes you’re going to be really comfortable and other times you’re not going to want to share anything. You’re going to have to push yourself. I think there’s something about giving them that choice, and naming it, too, that feels powerful for them. But I’m not coming to put words in their mouth. I could be making something completely abstract and still be having a cathartic experience because I am creating something out of a chaotic life, experience, question, or worry, and that is the beauty.

IZ: The act of creating.

RW: It doesn’t have to be a re-telling of what happened to you. I think some genres more than others just placate to “just re-tell what happened,” and as a poet I can say poetry is very good—especially slam poetry—at having people get up and tell these really traumatic stories.

IZ: I think there’s power in that too.

RW: There is, absolutely. But I also think there are other ways to be powerful, and other ways to heal. I think the first step is the re-telling. Telling what happened to you and what you feel about it is very powerful, but it’s also a skill for young kids of color and young people from marginalized groups.

IZ: I think that’s the end result, that’s not the very beginning, right? I went from journalism to creative writing; the bridge was spoken word. The late 90s spoken word was where I found my voice. It wasn’t books. I wasn’t trying to limit myself to what I read in books. I was reading, but none of that really related to what I was interested in. It wasn’t until I saw somebody my age get in front of a mic that it was a thing, you know?

RW: Yeah!

IZ: People were getting in front of mics and just—

RW: —bringing it—

IZ: —coming up with stuff, you know? You had to read, because you had to bring some new information that blew people’s minds away, and it was the way that it was told. People were telling it in different ways and took on a persona. That was the most powerful thing. If I ever have to credit a book or a time, I’ll have to credit the underground spoken-word movement in New York City in the late 90s. I don’t know what was happening in the rest of the country, but in the late 90s, right before Def Poetry Jam—

RW: That was a powerful influence.

IZ: The people that I was going to poetry events with started that. I knew the people who ended up on the show. I auditioned for the show, didn’t get on, but there was such an electric movement there. That is where I became a writer.

RW: Performance goes hand in hand. It goes along with what we were just saying about giving voice—literally voice—in your story, not just in this abstract way. You wrote it, but now what are you going to do with it? How are you going to share it out into the world? I love to get young people on their feet, even if they can just say one line. Just try to practice letting your voice speak the words that you wrote. I was extremely shy when I was a kid. In my personal life, I’m not the life of the party; I would never share my work. Even now, when I have to do something—an event, a reading—I get very nervous. I remember a teacher saying to me, “Your voice is powerful. You have to use your voice.” I would write something and ask, “Will you read it for me?” He did that a few times, and then he said, “I’m not doing that any more. If you want people to hear your words, you have to say them.” I wanted to share my work, but me actually saying it, standing in front of people? Absolutely not. As I started to do it, I realized people are moved by my words; there was some power in that. How do you feel getting your voice out to the world?

IZ: Now that I have to speak and advocate for my work and my intentions, I realize my time in front of the classroom has helped me to speak in front of an audience. I just did a video for HarperCollins and I realize I sound like a teacher—the intonations in my voice when I have to talk about myself. I don’t know if that’s good or bad, but I’m taking those skills of trying to get young people to understand me, to get them to understand my point of view, my intentions for them as readers or potential buyers or what have you, using those same methods in the classroom to share with a larger audience. I realize not everybody who writes a book has been in a classroom or has had to speak in front of children, who can be the most judgmental audience. High school girls will judge you up and down!

RW: They give you real feedback.

IZ: I always know; it’s just in their face.

RW: If I’m coming into a writing workshop in a school system that’s very logical and mathematical, how do I get other learners engaged in a lesson? A lot of times, performance is a way. If I know we’re going to talk about some serious topics that day that may bring up sadness, anger, or frustration, you feel that emotion in your body. I’ll take them through an activity where I’ll just have them act at their seat. I’ll say, “Show me in your body what sadness looks like, level 1, level 5, level 10.” We go through all these emotions in their body. They’re getting prepped for this serious poem that we’re about to read. I have this hook for the kids who needed to do something with their body, because they’ve been sitting at their desks all day writing. Now they’ve gotten some energy out. Also, they’re now maybe a little more emotionally prepared for what’s going to happen. A lot of the times, performance is integrated into my workshops as a way to teach the lesson. On day one, you have to share a line of a poem or do something in class that gets you practicing for the whole time you’re with me. You don’t just create, you share. By the time they really do have to get up on stage in front of an audience, they’ve been prepped for that over that period of time.

T&W: Tell us about your new books, who you’re reading now, and your current relationship with being a writer and an educator.

IZ: American Street is my first novel, and it’s a weird place to be in because I have other books that I’m writing, we’re now in interesting times, and I’m having thoughts on how to position my voice. I realize that the satisfaction that I’d thought I’d have by having a published book is not quite there. I’m re-evaluating goals, because I’m realizing it’s not it. The book is not it. It’s the platform that the book can provide. I can speak about the content in the book. I get more satisfaction in sharing ideas, examining ideas, really being in a space where I get young readers to re-examine their ideas and sharpen their critical-thinking skills. I want to go back into the classroom in a different capacity and engage teachers as well, because I realize they’re the real gatekeepers. One child may read my book at face value and not get much out of it, but the book can have real power—any of our books can have real power—when there’s a teacher there or any educator who can help unpack the ideas. I really appreciate the work that we do—the social justice work, the education work, and the writing—because I feel that the writing by itself? I’m not satisfied with that personally.

RW: I don’t know what to say about that. It feels really good to be at a place in my life where there’s balance.

IZ: Right, that’s what I’m looking for.

RW: I think now I’m in a very sweet spot. It’s very rewarding that I’m able to write full time now and do author visits where I’m really in full control; I don’t have to turn in a lesson plan and all of that. I can come, really engage with students, really talk about the issues I want to talk about, and sometimes take them through a writing activity. That has taken me literally around the world and I never ever knew that would be possible for me—I didn’t even know to dream of that.

IZ: In terms of reading, I like my nonfiction texts. I just finished reading Jason Reynolds and Nicola Yoon, because I interviewed them for the National Book Awards website. I want to go back and read more of Jason Reynolds’ books.

RW: You have to.

IZ: know, yes.

RW: As Brave as You is so good.

IZ: I’m reading This Side of Home, because with my next novel I’m looking to see what you do with gentrification. Mine is more of a love story. A re-telling of Pride and Prejudice set in Bushwick [Brooklyn]. I’m not one of those authors who says, “I can’t read it because it’s too similar.” I read it if it’s similar to mine, just to see how certain things are tackled. And I can’t mimic it. That’s not possible. So I’m reading the classic and I’m reading how other writers like Nicola Yoon tackle teen love in the midst of gentrification.

I’m reading This Side of Home, Renée, to see how you handle a character with a strong activism voice where the angst is there, the skepticism, and the sass. That’s my character, but she’s different from yours, so when I did my writing-for-children program, I studied writers and how they write as text for my own writing. I’m also reading Create Dangerously by Edwidge Danticat, because with the sad news of late—the dark days—I needed something to hold onto. I need to say, what am I doing now? How do I approach this world now? Danticat’s whole thing is, “Create dangerously, for people who read dangerously. This is what I’ve always thought it meant to be a writer. Writing, knowing in part that no matter how trivial your words may seem, someday, somewhere, someone may risk his or her life to read them.”

RW: When I’m writing fiction—novels or long works—I read poetry. I feel like as a fiction writer, I can learn a lot from poems, which are huge stories in a short amount of space. I’m really thinking still about word choice. I don’t want to get lazy because I have all this room. I try to write in a very concise way like poetry does, and potent, strong. Hopefully! That’s the goal. My go-to poets for inspiration for writing and for life—when things are hard like they are right now—are Lucille Clifton, always; Gwendolyn Brooks; and Langston Hughes. For This Side of Home, I read House on Mango Street many times over. I just needed that book in my life as a model text almost. I love Sherman Alexie and what he does, and you’ve mentioned Jason Reynolds. I love Jacqueline Woodson’s work, but more than that, I look to her and how she moves in the world as a woman of color, who writes about black girlhood, who speaks out against injustice, and also maintains this grace about her. I’m also looking at writers who have had longevity of a career. I look to her as almost as a role model.

IZ: You and I both. You and I both.

RW: She’s doing it right. She’s figured it out. So, I’m looking to her for wisdom from afar.

IZ: Same here. And I’m realizing she may not have figured it out; I don’t think there’s anything to figure out. You’re just your authentic self. Getting advice as a debut author, I realize that you have to follow your own heart. There are people who say, “This is how you move in the business,” or my husband, who talks about navigating the deal with regard to teaching. I’m realizing that I have to move through this world as a human being and not only to have the plan laid out.

RW: That, hopefully, goes towards our writing too. I’m not interested in writing books because this is “hot” right now, or this is what teens are loving so let me get on this. I want to write books about characters that I care about, things that I’m interested in, and then put it out in the world. Whatever happens with it, happens with it.

T&W: Has anything changed or amplified in its importance for either of you after the fallout of this Presidential election?

RW: In many ways, it is the same work, right? I feel like I’ve been a part of the conversation with young people for a long time now about using your voice to stand up against injustice, what you can do, and how is your art going to interrupt oppression. I’m not moved in that way of feeling obligated in a different way, just reminded of how important this work really is, along with an urgency to do more of it. I don’t feel a new charge because I feel like I was doing this work, and I know a lot of educators who already were.

IZ: For me it was different. I did feel there was a charge, because I think I was halfway involved before. I think there was a lot of fear for me in how I approached topics with students in the classroom, even with my husband now in the classroom, even as a new author, even as someone who is writing essays and trying to figure out how to present myself in the world. I tend to be more on the radical side in terms of really loving the idea of rites of passage in the way that indigenous cultures have done it, in terms of having young people really dig deep into who they are and their place in the world, whether the classroom environment or the public school environment that may not allow them the space to do that. I feel like I’m going to revisit some of my personal values that I bring into my work. By rites of passage I mean to tap into what it is to be human for a young person. I’m realizing, having a teenager, there’s certain things I’m not sharing with her that I know about what it means to be a girl of African descent that moves beyond being a black girl, which is still limiting; what it means for her to be a Caribbean girl, plus her father’s West African—to take all those parts of herself and start to examine it. Even if I work with kids in Brooklyn I take into examination, “You are all not just kids of color.” I remember being in a classroom and the teacher told me there were nine different languages being spoken in that classroom.

Now I feel like we’re at a point where I don’t want them to be just a classroom of nine different languages or kids of color. No, let’s stop and take into account and really examine the fact that this girl is Fulani, French, and English; and this boy speaks Arabic, Spanish, and English—really focusing in on the specificity of these children’s experiences and what that means in the world. In my novel, my character is Haitian American and she practices her traditional Vodou religion and moves to Detroit. She takes it with her. There is a specificity in that experience, and there’s also a universality in that experience. What happens when you bring your Fulani into a Brooklyn neighborhood and you’re Muslim and your teacher is Jewish, and what kind of conversation has happened.

In Nicola Yoon’s The Sun is Also a Star, her character is Jamaican American and the love interest is Korean American, and that blew my mind away, because I’m in a very Caribbean neighborhood and you know how many Koreans are around? They’re just invisible to us. They own the farmer’s market, the nail salon, and the beauty supply store. Her thing was that we’re connected, you know. I could imagine a Jamaican-American teen girl walking into the beauty supply store and there’s a teen Korean boy working behind the counter, and why not? Why can’t they fall in love? Move away from the generality of who you are in the world and speak to your own personal experiences. Rites of passages in the indigenous way of looking at it is not about you coming into the group or you graduating high school to be part of a society to assimilate; it’s you saying “never mind” to everybody else. Who are you? Let’s go back inside yourself to realize who you are and how you are supposed to walk in this world based on those personal experiences.

RW: I’ve said this a lot, but I feel like I want to say it from a mountaintop. Social justice education is not only for schools or communities where there are people of color or people who have been marginalized. I so strongly believe that we have good evidence of that and now, whatever is the opposite to the picture in a person’s mind when you think of spoken-word poetry classes in public schools—the opposite of that—an all-white, all-male, affluent school. We need that there. We need those conversations about race, class, and gender issues.

IZ: It’s happening in the private schools, but—

RW: —not in the public schools. Especially after the election, I am more and more wanting to have these conversations in mixed company and not always in the segregated communities. These students are learning how to give voice to their dreams, how to fight injustice, and write their personal stories. They’re being told they matter. If a whole other group that is actually going to be in a lot of power is not being told that those people matter, they’re not reading diversely, we get what we have.

I’m definitely thinking about how to teach and bring my books out of silos. Yes, there’s an African-American girl on this cover, but a white child can read this book and get something out of it. It is not shelved as, “This is a book for girls or for black children.” I’m thinking a lot about how to be more vocal even to schools. I’ve gone to schools and had teachers say, “My girls love your book,” or they’re surprised if a boy likes it. All of those things that we categorize, I want to just mess with all of that! Because we need to. We need young men understanding sexism and all of it. That’s important to me too.

In piecing it together, class is I think a big part of it. It’s about race, but it’s about class. I think we’re at a point in our country where we could use some great conversation about that as well. All the intersections of who we are. It’s not just class, it’s race. It’s also gender, it’s also religion. All of that does matter and is important to think about when writing for children and when teaching them—to let them bring their whole selves to the curriculum is so necessary and crucial, especially when we are being erased.

T&W: Renée, can you talk about the purchase of the Langston Hughes home in Harlem that just took place?

RW: I’ve lived in New York for 11 years, have walked past the brownstone all this time, and have been sad that there weren’t programs happening in there. It wasn’t a museum; it wasn’t a space being used. Not that it was vacant. The owner was living in it and there were things happening, but it was sad to me that it wasn’t a space to preserve Hughes’ legacy. The first nudge was gentrification in Harlem. At the time, I was on a book tour and going around the nation realizing it’s not just New York and Portland. It’s Austin, Texas; it’s DC. Collecting all these stories from young people and coming back to the neighborhood and almost not recognizing it. I thought, “Where am I?” Like the girl in my book, she actually inspired me. I can’t keep talking to young people, telling them to stand up for what they believe in and to fight and use your voice for something, and I don’t do that. My books were not enough. In my book, I’m being a writer. That is not activism. I actually need to do it in my own life.

That’s what pushed me to start thinking about the brownstone. I was nervous and I wasn’t sure I had time and resources to do this, but I had to try. If I didn’t try and it became expensive condos or a coffee shop, I would be so sad and angry. And so, we tried. And it worked. The community—especially the kid-lit community—came through in ways I cannot begin to describe. I was speechless many times over at the generosity of people and at the fervor and passion with which so many people had been wanting something to happen there. We need spaces where people can come and create and we need to preserve and keep on record what has happened in this country.

We signed the lease just a few weeks ago. There are plans and we hope to be up and running for the community in February for his birthday.

IZ: When is his birthday?

RW: February 1. We will definitely announce the launch when it happens. So that’s my project right now. It’s a little all-consuming. Besides that part of me, I’m working on a middle-grade novel about Betty Shabazz, co-writing it with Ilyasah Shabazz, her daughter. She grew up in the 40s in Detroit, so it’s been interesting to research because I didn’t know a lot, and I feel like a lot of what we hear in school about the 40s, 50s, and 60s is the South, and then there’s one sentence, “But in the North, they had rights.” Jim Crow wasn’t in the North is all your hear, so it’s been really fascinating to learn about what was life like for African Americans living in the 40s in this booming city. What was life like and what type of activism birthed out of the privilege of not being in the South, but also being in a racist nation? How does a brown girl keep her dignity and joy intact when growing up in that kind of a world? So, I’m excited about that book.

IZ: [For her novel American Street] I had to research Detroit—

RW: I know, we talked about how both our books are set there.

IZ: We’re on a journey together.

RW: I was also writing about Harlem, and so were you. We’re on this wave right now. We could do a joint reading somewhere. We’ll talk about. We’ll figure it out.

Teachers & Writers Magazine is published by Teachers & Writers Collaborative as a resource for teaching the art of writing to people of all ages. The online magazine presents a wide range of ideas and approaches, as well as lively explorations of T&W’s mission to celebrate the imagination and create greater equity in and through the literary arts.