The young woman in the corner of the classroom opens her journal and begins to read aloud.

“Today, the world seemed to fall silent,” she says.

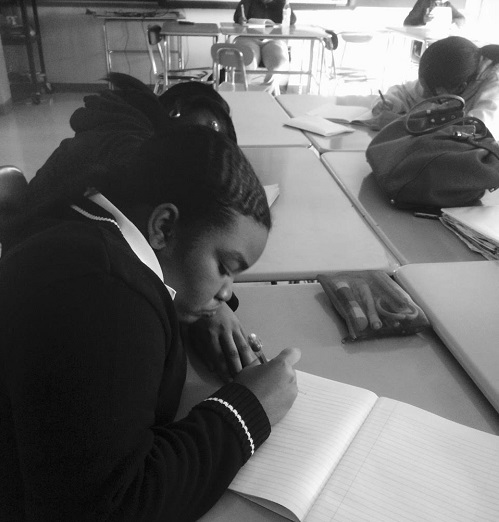

The room itself is hushed, the students hanging on the next words she will speak. The door blocks out the rattle of other girls elsewhere in the building, but it is hardly necessary. Since the election, the atmosphere has been unusually heavy in this school normally buzzing with the music of young women at work. The air has been filled with apprehension about this new America and what now seems to lie ahead for this room of first-generation women, most of them African American or Muslim.

As one, they turn to the soft-spoken girl in the corner, giving her all their attention.

We wait in the silence and prepare ourselves for whatever comes next.

Rewind the clock a week.

I stand in front of this class of young women and say, “I’m going to do something now I’ve never done before.”

I watch as heads pop up, swivel my way.

“I’m nervous about this thing,” I say. “I don’t know how it’s going to go.”

The room settles, girls turn from their friends and face me. I’m a new person here. They don’t know me and I certainly don’t look like a teacher with my over-sized sweaters and twelve-year-old face. I look, save the non-uniform and skin color, like one of them. One of the thirty or so high school girls looking at me with faces scrunched and eyebrows raised.

“I’m worried you’ll judge me.”

“This is a safe space,” one girl says, a sneer of sarcasm in the back of her words.

They’re ninth-graders, so roughly fourteen years old or thereabouts. Deep into their teenage girl-ness and caught up between wanting someone to listen and wanting to push the whole world out, keep others at bay with derision. I have only twenty-five weeks with them (once a week over the course of the year), so I’ve got to find a way to get to them and quickly, to establish trust so they’ll open up and allow themselves to be vulnerable.

“How many of you write in a journal?” I ask them.

Maybe three or four hands pop up.

“How often do you write?”

“Maybe once every couple of weeks.”

“Good,” I say. “And how many of you write letters to your friends? Pass notes during school?”

More hands go up, some girls giggle at one another in private jokes.

“Well,” I say. “A little bit about me. I’ve written in a journal every day of my life since I first learned to write.”

“Every day?”

“Every day.” I smile. “And how old do you think I am?”

“Twenty-two.”

“Twenty.”

“Twenty-eight.”

“Nineteen!”

“Oh,” I say. “You’re just trying to butter me up.”

The girls laugh.

“I’m thirty years old.”

I won’t pretend I don’t love the shouts of disbelief that follow this part.

“And I’ve been writing in journals since I was six, every day, so you all do the math.”

They’re impressed, or at least they feign it.

“What do you write about?” they want to know.

“Anything. Everything,” I say. “Things that are going on in the world, what I’m feeling, about life events, thoughts, etc. In fact, at this point I don’t really know how I feel about something until I write it down.”

“Wow. That’s crazy,” someone says.

“Yeah, I know.”

And I do know. I’ve used writing as a psychic crutch my whole life. I don’t know where I’d be without it. And fourteen was a particularly rough time in my life. In fact, writing—quite literally—saved my life.

“That’s why I’m nervous about this thing I’m about to do.”

I pull a tattered black book from my bag. There are loose-leaf sheets sticking from its browned edges and a small white box with purple lettering that spells out my name in the center of the cover.

“For only the second time in my life,” I say, holding the book aloft. “I’m going to read from my journal, out loud.”

To say that the room is silent is an understatement.

November 3rd, 2001

Some birds aren’t meant to be caged; their wings are just too bright. My mom thinks I wasn’t serious about getting some money and just leaving for Europe. They think I’ll ruin my life. If I’m happy and I love what I’m doing I can’t ruin my life. I can only ruin it if I’m not happy. I’m not happy here. I’m trying to live a good life, but that’s not making me happy.

The entry goes on, but you get the picture. With a thirty-year-old’s lens on it, the passage is a seemingly angsty and somewhat silly thing by a teenage drama queen. But zoom into that time and you can see the very scared and angry girl I was, lashing out. I struggled with some serious issues at home and this was my outlet, my void to shout into, my platform for parsing my ideas and working out my feelings of inadequacy and fear and anger.

And I did. In my journals I have tangible evidence of my evolution as a human being. Rather than doing something harmful to myself, which was an imminent threat for most of my teenage life, I transformed those feelings and thoughts into positive actions. I’m a teacher now. An activist. I’m a person who strives to be better, to see and make the world better. Keeping a journal all these years has taught me that I have to know myself if I want to change the ugliness and oppression in the world. That is what I was doing in the entries I read to my students: learning who I was. At times, I found I was my own worst oppressor, my ugliest enemy. I was the person holding myself back, caught up in a negative feedback loop of my own design.

My mother was in and out of my life as a teenager. I spent years blaming her for my unhappiness. I spent so much time doing this that I neglected to look inward, to reflect on what I’d done and how this finger pointing and anger was only keeping me from growing in other ways. Even now, I’m still learning to let go of that pain. And letting go of that requires me to see my mother as a human whose heart is also hurting. It can be a long, hard process to reconcile with our own demons, but doing so can give us the power to change not only our own lives but the world around us as well.

The girls are hooked. They ask me probing questions about my background, my thoughts, the pain I went through. It’s a delicate balance talking them through it. I want to be honest, but I don’t want to influence anyone in a negative way. And our struggles are different. I’ll never know what most of them face.

Conversations break out amongst the girls as they compare some things I said in my entry to their own home life, as they contemplate things they might write. One girl quietly asks me, “Did you ever think about suicide?”

The answer is yes, more than yes, but I say, “I had some dark moments that I worked through, yes.”

“That’s what I’m dealing with,” she says, just above a whisper.

I nod. The rest of the class can’t hear us, so I lean in and quietly say, “We can talk about that whenever you want. And I would definitely encourage you to write those thoughts down, talk yourself through exactly what you think.”

She nods. “I will,” she says.

And here is a space opening up. A tiny crack in their armor where these young women will allow themselves to be vulnerable and to experiment with me in this game of writing.

“Now, it’s your turn,” I say to the room.

As class nears its end, I give them each their own journal that they’ll be writing in throughout the year. I tell them my number one rule is that no one can read this journal without their permission, including me. I tell them this journal is me giving away my control to them. I tell them that what they do with it, what they write, what they think, is up to them. The girls decorate their covers, only half believing what I say.

A week later.

It’s the day after the election. No matter who you voted for, the election was divisive to say the least. And here is a room full of young women of color, many first-generation Americans, who are scared. They could not yet vote but are among the most vulnerable to the changes the new Administration will bring. Theirs are the voices that have been repeatedly excluded and ignored throughout the world’s history. And today, once again, they find themselves facing great uncertainty without having any choice in the matter, without being able to make their voices heard. There are people out there who not only don’t want to hear their voices, but deliberately want to silence them.

How they respond varies, but the point is that they respond.

Today, the world seemed to fall silent

everyone with their heads down

not even the lady who screams

‘hello New York’ on the subway

every morning

had joy in her voice.—Sharnice

They have a lot to say about the election. But also a lot to say about life, love, family, and the future, among other things. Their journals are a place for them to work out their fears, intentions, hopes, and frustrations.

You helped to give me life

but then you left me

to starve for something

that I craved from

the beginning

which was love.I believe that having

a child is a gift

from the god above

but you abused that

gift and left it to rot.

You’ve turned a

beautiful thing

and twisted into an

incomplete junkie.—Renee

Some of what they write is light-hearted, some dark. Some of it is just a day-to-day snapshot of what captures their attention. I tell them even these—the short paragraphs about what they ate for lunch or who was seen with whom out at the movies—is important.

“Why?” they ask.

Because it’s carving out your space in the world, I tell them. The good, the bad, the generally mundane. It is giving permission to yourself to be who you are. And once you give that permission to yourself, it becomes easier to demand the world do the same. You don’t have to be “profound,” you don’t have to be “deep,” and you don’t have to be happy, sad, angry, or even grammatically correct. You only have to be.

This lesson, using journal writing to teach creative writing, is nothing revolutionary. People throughout the centuries have kept diaries. Philosophers, presidents, scientists, novelists, and others have used it to discover their selves, their voices, the things that made them alive on the inside.

It is a practice that offers the possibility of transforming the mind through the self, through one’s own reflection, without the influences of outside voices. To be able to identify and look at one’s own shadow self, the negative most of us shy away from because recognizing our own ugly can be a deeply humbling or even traumatic thing, is an act of bravery.

Asking students to write about their lives may not be some grand lesson plan that will change the way they learn, but it offers a relatively simple and straightforward way to engage students in the kind of reflection that can bring about something profound: a revolution in how they see themselves and their place in the world.

To put each other in a box, to limit another human in some way, is to go backwards. History has shown us this over and over. There are a lot of people who think these young women—these first-generation and immigrant women of color, these African-, Hispanic-, and Muslim-American women—don’t deserve a place in the world, who think these girls shouldn’t have a voice. My job as a teacher is to carve out a space, no matter how small at first, and help these girls expand it from within. These journals are the ground from which these women will grow.

So perhaps they are the makings of a small revolution after all.

Photo (top) by M.K. Rainey

M.K. Rainey received her MFA in fiction writing from Sarah Lawrence College. She currently teaches writing to the youth of America though Community-Word Project, Wingspan Arts, and The Writing Institute at Sarah Lawrence. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Cider Press Review, Litro Online, Equinox, KGB Lit Journal, The Grief Diaries, and more. She co-hosts the Dead Rabbits Reading Series and lives in Harlem with her dog. Sometimes she writes things the dog likes.