For me, the “reward” of poetry in the classroom is seeing how paying attention to and concentrating on what’s “on the page” can lead students to glimmers of incredible reflection. The paradoxes and complexities of their lives—navigating personal love, family grief, and desire—are ballooned, brought to their front door, by the elevated phrasings, diction, and sounds of a poem. This often means that students must confront their own personal histories, come to understand themselves within a larger social context, and see their lives reflected in a deep engagement with words.

So, how to get students to pay attention? In the lesson that follows, I outline how to teach close reading skills to students who have no formal experience with poetry by emphasizing the importance of looking for patterns of repetition in Robert Hayden’s “Those Winter Sundays” and Drake’s “Nice for What.” When I first mentioned this lesson plan to some of my colleagues, they were excited, I think, by the possibility of pairing Hayden with Drake. The idea of pairing former U.S. Poet Laureate Robert Hayden with Canadian international rap icon Drake might not be obvious, but I wanted a way of getting my students’ attention. At the time, many of them were re-listening to and discussing Drake’s album Scorpion (2018) outside of class. I knew I wanted to discuss the importance of repeating sounds and literary devices that feature repetition in poetry, and introducing an old canonical poet, however moving, often leads to drowsiness in the eyes of my students, who rarely read poetry outside of my classes. That’s when I decided to tie in Drake. Hayden’s lines, “What did I know, what did I know / of love’s austere and lonely offices,” reminded me of Drake’s song, Nice for What: “care for me, care for me, you said you’d care for me.” Both Hayden and Drake use repetition to discover and define the love they have for the people in their lives, and tracking the repetition of sounds and word patterns provided me and my students a map to reflect on that love—both personally and in the context of Hayden and Drake’s lyricism.

Both Hayden and Drake use repetition to discover and define the love they have for the people in their lives, and tracking the repetition of sounds and word patterns provided me and my students a map to reflect on that love . . .

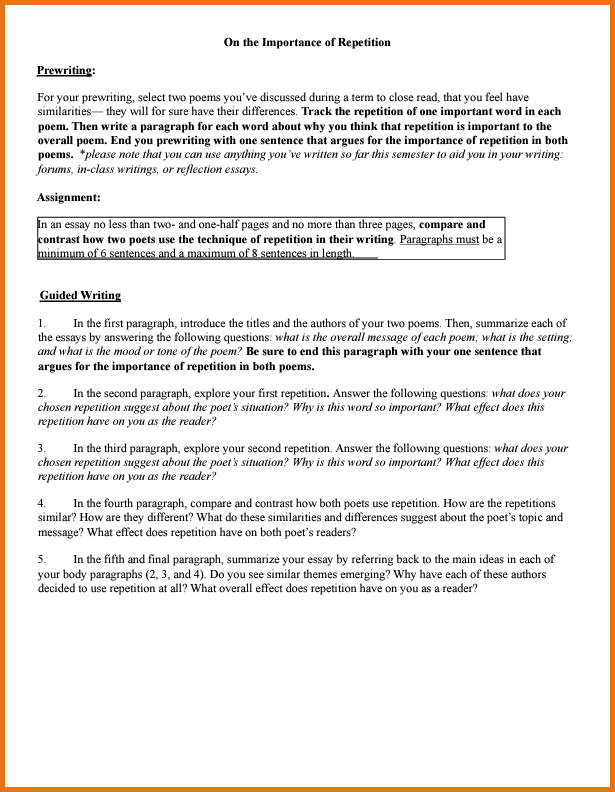

On the Importance of Repetition

Repetition forms the building blocks of rhythm and of the larger fabric of associations that make up a poem’s spirit and architecture. It’s a pattern-building, mnemonic process which instinctively informs the movement from attention to pleasure and is the joy of both reading closely and thinking about daily habits beyond language. Making my students aware of how daily experiences touch in us certain patterns and rhythms is important to setting the tone for our conversation about Hayden and Drake.

I begin the lesson by discussing with students how repetition informs our everyday lives—walking through the front door of our homes, waking up in order to get to work on time, the evening sunset. I ask them to write—in list form—for 7-10 minutes about the kinds of objects, people, and activities they return to on a regular basis. As most of my students are aspiring nurses already working in hospitals, we spend a lot of the time discussing how caring for people in clinical settings often means returning to them: managing prescriptions, performing tests, adhering to feeding schedules, etc. The discussion also returns to picking up children from school, which, for parents who are also students, often means managing time effectively. The larger theme which emerges out of our discussion is that repetition builds a sense of security into our daily lives: the comfort of healthy patients, the welfare of a child’s safety. Although they might seem mundane, the commonplace acts of repetition we inhabit regularly have about them a metrical quality. They ensure the completion of tasks and build and relieve worthwhile tensions. They compel a kind of lyric attention, of memory and inspiration, and ask us to return to people and to things, giving us a larger sense of connectedness. This is what poems do, I tell my students. They ask us, quite literally and line by line, to return with our attention to words, to people, and to things.

Robert Hayden and “Those Winter Sundays”

I then hand out to students a one-sheet called “Close Reading and Interpretive Claims” or The Method: a step-by-step approach to breaking down texts, objects, and images. The Method, taken from David Rosenwasser and Jill Stephen’s book, Writing Analytically, is a list-making procedure and writing exercise meant to give students a hands-on approach to close, active reading.

The lesson on Hayden’s “Those Winter Sunday” and Drake’s “Nice for What” focuses only on step 1 of the Method: locate and list exact repetitions. Hayden’s “Those Winter Sundays” and Drake’s “Nice for What” are perfect for The Method because both artists use the repetition of sound and of a percussive vocabulary as instructions for understanding their work.

Hayden’s poem marries the sprung, swinging percussion of his compressed lexicon—blueblack, cracked, ached, weekday—with the spirit of reconciliation that the poem comes to embody: “what did I know, what did I know / of love’s austere and lonely offices?” Drake’s “Nice for What” revels in a similar sound and ethos of lineage and admiration that draws him near to us. His refrain is a remix of Lauren Hill’s 1999 hit single, Ex Factor: “care for me, care for me, you said you’d care for me / there for me, there for me, you said you’d be there for me.” Though Drake’s lyrics appear less taut on the surface, both Hayden and Drake see in their use of repetition an epiphany of praise for lineage and for the singular loves who have defined them.

Twice we read Hayden’s poem aloud as a class and discuss our initial observations. For students who don’t have much experience reading poetry, a good entry into any poem is listening to its sounds. We make a list on the whiteboard of all the repeating sounds: blueblack, cracked, ached, weekday, banked, thanked, wake, breaking, call, chronic. We notice the hard, percussive K sounds are repeated 10 times. We then move on to listing exact repetitions of words and phrases:

Sunday (x2)

cold (x3)

What did I know (x2)

him/his/he’d (x4)

The act of making lists, I tell my students, is an act of discernment. By identifying these repetitions as a class, we are implicitly making interpretations about the poem together. For instance, the repetition of cold three times, we notice, immediately makes apparent its binary opposite, warm, which is only ever mapped out according to its equivalents: blaze and fire. At this point, we haven’t yet begun to speak about the relationship between the poet and his father. We are charting the language and learning how to read the poem according to its sounds. One student points out that the hard, percussive K sounds are Hayden’s way of implicating the harsher elements of winter, a season that, when put up against the poem’s motif of fire, sets the tone of reconciliation. We conclude that, in the poem’s main repetition—“What did I know, what did I know . . . ?”—Hayden discovers the harmony of sound that embodies the poem’s spirit of admiration towards his father.

Drake and “Nice for What”

One reason Hayden’s “Those Winter Sundays” pairs well with Drake’s “Nice for What” is because both use repetition as a device for layering and harmonizing different textures of sound. Drake’s song meanders, whereas Hayden’s poem is formally tighter and more discrete. However, both Hayden and Drake use repetition to chart out melodies which suggest admiration and reconciliation toward their respective traditions. As a class, we read the lyrics and watch the music video for “Nice for What.” It’s easy to get lost in the verses’ maze of sound-play, so I focus the discussion on Drake’s chorus, which is a remix of Lauren Hill’s “Ex Factor”:

Care for me, care for me, I know you care for me

There for me, there for me, said you’d be there for me

Cry for me, cry for me, you said you’d die for me

Give to me, give to me, why won’t you live for me?

On the white board, we make a list of exact repetitions: for me (x10), care (x3), there (x3), cry (x2), give (x2). We also point out the different rhymes in the chorus: care and there; cry and die; give and live. One student notices the coiling effect the chorus has throughout the song, as if, she says, Lauren Hill is an omnipresent force looped in and out of Drake’s verses. I also want the music video to be as much a part of our discussion as the lyrics are. Another student points out how Drake’s decision to remain on the side-lines for most of the video empowers the 20 iconoclast women (such as Misty Copeland, Rashida Jones, and Issa Rae) who are the recurring centerpieces of the video. Many of the students know well Hill’s “Ex Factor” from her debut album, The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill (1998), and they are quick to point out how the combination of powerful iconoclast women and the looping remix of Lauren Hill makes Drake more than just a “male cheerleader”; the thoughtfulness and savvy of the video actually feels sincere, one student says. Like Hayden, Drake’s remix of Hill’s “Ex Factor” is hymnic. However, one of my students points out, where Hayden is subtle, Drake announces his intentions like an anthem.

It is a myth that, in order to understand poems, one must always know what is going on. If you have never closely read a poem, you are drawn first to the repetitions and textures of sound, then you begin to discover the narrative elements. Following those initial intuitions of sound and texture is actually how students begin to form personal relationships with poems, a kind of research that makes students into lifelong readers. The acts of breaking apart, of counting, and of listing patterns of repetition as a class gave my students a system and a practice for discovering the larger associative frameworks which were the hearts of the poems they were assigned to read, and when it came time to write their final essays “On the Importance of Repetition in Poetry,” they used the skills learned from our class discussions to develop the conversation around repetition in ways that felt fresh, detailed, and insightful. I specifically mention that, in writing their final essay on craft analysis, they should celebrate being an authority on the topic of repetition in poetry, that their attention to the subject throughout the semester—alongside others like assonance, consonance, anaphora, and rhyme—welcomes such exuberance. Particularly in the lesson on Hayden and Drake, I wanted students to feel themselves thinking, to feel the pressures and tensions of making leaps, following language and sound associatively, and, in turn, to feel the joy of surprise and discovery in the acts of reading and writing literally. What students ended up with was rich, clever perspectives about how repetition informs creativity and how creativity informs their lives.

Alex Bernstein

Alex Bernstein’s poems and essays have been published in Narrative Magazine, Hobart, Bellevue Literary Review, West 4th Street Review, and elsewhere. Included in Narrative Magazine’s 2022 list of “30 Below 30,” new and emerging writers, he is a graduate of Columbia University's MFA program and an Associate Professor and Executive Director of the writing centers at Mildred Elley college.