My calendars have always been marked with stars for two important occasions: Independence Day and the first day of school. If I close my eyes I can still taste the red, white, and blue of rocket popsicles at 4th of July parades, and smell the lingering char of fireworks sizzling skyward from a cul-de-sac block party. As a child, Independence Day was an anthem sung by Martina McBride; it was white doves and freedom for the oppressed, and victory-colored candy. As an adult, I haven’t celebrated quite as freely. Knowing what the day represents for the Native American peoples who sunk roots in this soil long before European ships arrived weighs heavy on my heart.

As a teacher, I still look forward to the first day of school with the same excitement, but my anticipation is grounded in a sense of responsibility. I want my students to be able to contextualize the history of their homeland, and acknowledge what existed before settlers claimed the birth of a nation. Lately, I have been spending long hours contemplating what our nation’s past means for our future. What might the next hundred years look like, on our current trajectory?

We’re all too familiar with the colonial history of the continent: the quest for spices and trading posts that evolved into a full-blown conquest for power. We spend far less time thinking and talking about the way resources, land, and culture are still battlegrounds in our country today. The economic, political, and cultural oppression of First Nations peoples belongs not only to the past, but to the present as well, and—at this rate—will plague our future.

So, what does course-correction look like? Who is responsible for decolonizing the hearts and minds of Americans, and what does that process entail?

*

As the doors opened to welcome us to a new fall term, I took this question to the most powerful forces for change I know: the fully-loaded poets of my junior high classroom. I gave them this name, which I took from the song “It Is Written” by the Indigenous band Nahko and Medicine for the People. The term references poets who use their creativity and their words as vehicles for change.

When I first introduced the topic of Indigenous issues to frame our poetry unit, I met crickets. A few chairs squeaked, and a couple muted groans escaped the back row. Surprised, I engaged the class in a discussion about their reaction, and their resistance began to take shape. A thick layer of disappointment settled in my gut as I realized our stiff-armed, dried-up, and completely dispassionate approach to teaching about Indigenous peoples landed flat with this crew, many grades ago. The educational system I was part of had stripped the curriculum on Indigenous peoples of any emphasis on experiential learning—the foundation of Indigenous knowledge—and instead passed out textbooks recounting a timeline of battles and legislation. Textbooks accented by black-and-white photographs of residential school survivors, and lesson plans outlining a no-waste approach to buffalo. Indigenous culture had been turned into a two-dimensional caricature of the vibrant resiliency I witnessed on reserves, and heard echoed in the voices of Indigenous scholars.

No wonder the students groaned. I paused long enough to add my own lamentations to the mix. And then, we got to work.

*

Our inquiry centered on the theme of rootedness and tied the study of Native American people to an investigation of the students’ own cultural heritage. We titled our poetry exploration Rooted: Grounding in a World All Dug Up, and discussed what it means to be rooted in a culture, community, place, tradition, language, worldview, family, and belief system, and in ourselves. What does rootedness mean? I asked my students. Why does it matter, and what do roots have to do with identity? These questions were particularly interesting because I teach at a private Jewish school, and the students there had spent much of their lives learning how their own people—after having their religion, language, and personhood stripped from them across historical events from the Crusades to the Shoah—had dealt with such trauma. The result of this questioning on their part was that my students discovered a new enthusiasm for studying how Native American cultures had responded to similar traumatic events; they were able to approach the curriculum I had set out now with newly open minds.

We began the unit by contrasting the origin story of European colonizers with the origin stories of North American peoples. A helpful resource for making this comparison is The Truth About Stories, a Native Narrative, by Thomas King. King’s speech (later transcribed into a short book) compares the Biblical story of Adam and Eve to the founding myth of Indigenous peoples, which includes the story of Skywoman, the Iroquois mother goddess who descended to earth by falling through a hole in the sky, and Turtle Island, a Native American name for the continent of North America. We discussed appropriation, stereotypes, the democracy of species (the belief that human beings are not in charge of the world, but are subject to the same forces as all other living things), lost languages, immigration, the peoples’ relationship to the land, and the Seven Fires prophecy that marks the phases in the life of the people on Turtle Island.

Helpful resources for teachers looking to explore these subjects include books by Indigenous scholars such as Basil Johnstone, Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, Robin Wall Kimmerer, and Tomson Highway. I also handed out an age-appropriate booklist for my middle schoolers, which included graphic novels by Patti LaBoucane-Benson, The Outside Circle, and David Robertson, 7 Generations: A Plains Cree Saga, for anyone interested in exploring the subject matter further.

This exploration contrasted sharply with students’ prior classroom engagement with Native American culture, and even my most resistant trouble-makers weren’t groaning anymore. The content of our conversations started to seep into the hallways and infiltrate dinner table discussions. Some of the students’ parents spoke to me about how engaged their children were. Back in the classroom, we queried Indigenous notions of sexuality, creativity, humor, medicine, leadership, and identity. And finally, we integrated what we learned in these discussions into the creation of art and spoken-word poetry.

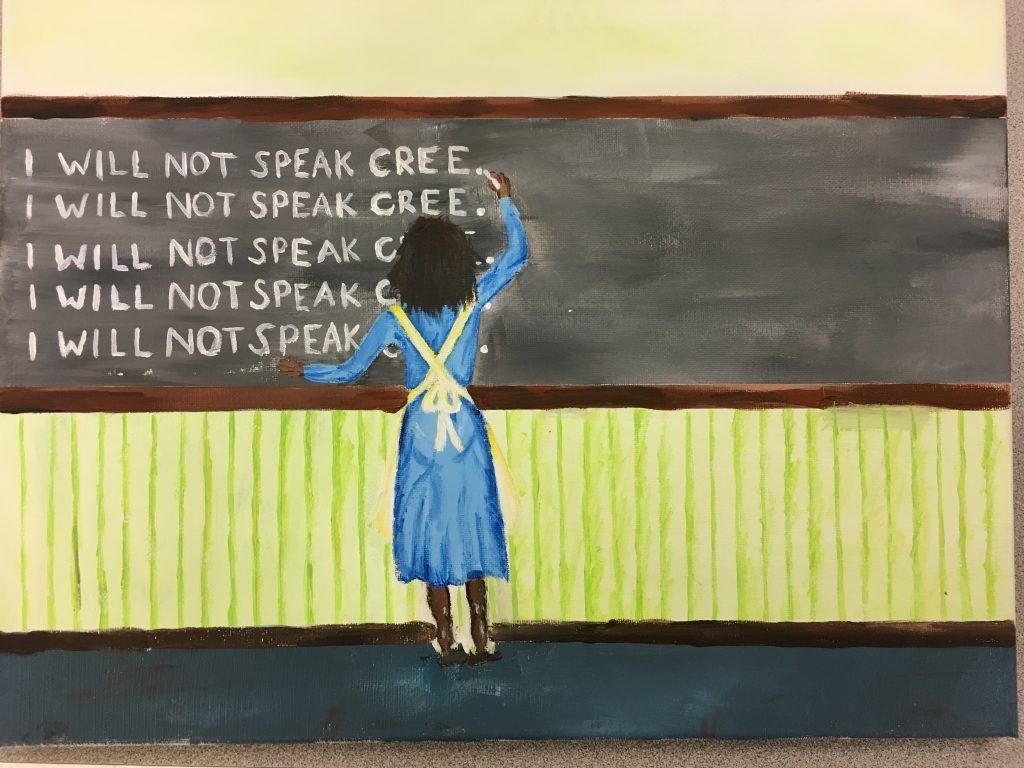

The art was created in small groups of three people. I pulled themes from the previous week’s discussions and created topic headings for each group, such as “What is a Treaty?,” “Teachings of the Medicine Wheel,” “‘I Will Not Speak Cree,’ and Other Tongue Ties,” and “Residential Schools: Scrubbing Brown Skin Raw.” Students then used mixed media (paint, crayon, found objects, etc.) on canvas to engage with the classroom content relevant to their particular topic.

The poetry component of the project lasted several weeks. We studied the elements of poetry; read various poems by Indigenous writers such as Rebecca Thomas, Richard Wagamese, and Lee Maracle; analyzed the poems structurally and thematically; and discussed them in class. I then gave students a prompt derived from the work of an Indigenous poet, and invited them to engage with the work by writing a poetic response. I created handouts titled “How to Converse with a Poem,” which outlined the steps of reflecting on an original work and creating a response poem, written in free-verse, dramatic verse, or the form of their choice. Through this process, they were encouraged to adopt what Mi’kmaq elder Albert Marshall calls Etuaptmumk, or “two-eyed seeing.” This is the capacity to hold both Western and Indigenous worldviews simultaneously, one with each eye, so to speak. As a final step, we invited parents and administrators to a poetry café, where students bravely took the microphone and shared their poetry in front of an audience.

The performances had some attendees in tears, some offended (work is often powerful when it offends), and all enraptured. Many parents who planned to leave after their child’s presentation stayed for the whole reading. My students described the event as emotional and profound. In the words of one young poet, the poetry “filled the empty space of the room with admiration.” I was amazed to see that the attitude of every student in my class had shifted with a completeness that was almost jarring. In their own words:

We are leaning in

We are listening

We are honouring your suffering

And your rising

They had gone from a sense of apathy and a lack of desire to engage to a profound willingness to learn, to improve, and to approach our work with an open mind. The change I saw in my students can be summed up by the contrast between the first and last paragraph of one of their most poignant poems:

You will no longer speak

You will no longer speak

You will no longer speakWe will now listen

We will now listen

We will now listen

*

As educators, we have a responsibility to guide classroom engagement with Indigenous issues away from the cultural appropriation that has marked so many of our interactions with Indigenous culture in the past and toward a more authentic engagement with our own history. Indigenous peoples made a home here long before colonizers poked a flag into the ground, and their culture holds a deep knowledge, woven into relationships and breathed into stories passed down from generation to generation.

I teach my students that the land we live on today in the United States is what Indigenous peoples call treaty-territory, which simply means we all have a responsibility to care for this land, as people who live on it. We are, by definition of our presence here, in relationship with the land, I tell them. This makes us treaty-people. As such, we have a duty to protect and care for this place where we make our home, but under our watch fish are floating belly-up in poisoned rivers, acid rain from chemical plants scorches the earth, and the First Peoples, too, are suffering. They are beating back addiction and abuse, and contending with the open wounds of suicide and poverty.

This year’s poetry café seeped into the bones of the students who participated, and elicited an emotional response from all who witnessed and shared in their work. My students reminded me that engaging with the process that led us here as a nation is an integral part of uncovering where to go next. Studying this history with new eyes created room for new possibilities, and new stories: stories of collaboration, justice, and healing. In the words of Gary Nabhan, we can’t move forward with restoration, without re-story-ation. In other words, our relationship with the land we live on cannot heal until we hear its stories—and the stories of its people. And so it is by seeking out these voices, and learning how to find our own, that we begin to honor what was lost. Only then might we have a hope of moving forward.

Scrubbed

by SS, SR, BJ, and EM (grade 9)You were told that your being, who you are as a person, was unclean

All your self-love and sense of self swirled down the drain in the bubbles of soap

While the open wounds allowed hatred, self-rejection and abuse to seep in

Time went by, and things are only slowly changing for your people

A people who suffered years and years of cultural cleansingEven though hard bristles scraped across your body

To take off the “dead skin” which was your culture, traditions, and deep knowing

Know that you were pure and whole just the way you were

a being with a beautiful language, communal way of life, and a true connection to the earthyou are not an “other,” or a “savage” to be tamed

you are a human being with a history created during the time of the sky lady

you don’t have to feel ashamed anymore

or have night terrors of the constant scrubbing that only made you bleedCrosses hitting you as black and white uniforms of an unforgiving God scrubbed to make you “white”

scrubbing to take the Indian from not just your skin, but soulPlease

never forget the pain inflicted

as you were forcefully cleansed

and told to be grateful that you were becoming white

that you could now fit into society in an “acceptable” wayDon’t just accept an apology

but continue to re-claim your heritage

REVOLTWe will support you through your revolution

A revolution to gain back your rich colors, your native tongue, your ways of life.

Continue to push through the colonial barriers to regain your selfWe are leaning in

We are listening

We are honouring your suffering

And your rising

You Will No Longer Speak

By MN, BE, and AS (grade 8)You will no longer speak

You will no longer speak

You will no longer speakCree,

The language that you were born into

You will no longer speak

The language of your creation stories

You will no longer speak

The language that comprises every fiber of your being

You will no longer speakA wise man once said that without language people,

“Cannot grasp their history, appreciate their poetry, or savor their songs”

Colonizers ripped your history, poetry, and songs from youYour words about:

Love

Creation

Connection

Were replaced with

Hail Mary’s

And yes sirs

The rosary indenting your fingertips

As you choked out the prayers

Slowly,

Forgetting your own,

No wonder your people rub their wounds

With drugs and alcoholYou were bullied and beaten,

Scarred by the people that took you away,

The men thought that they could erase your language,

But they were wrong,

Wrong for not valuing you as human beings,

Wrong for beating you for speaking your mother tongue,You are reclaiming your language through poetry, and song,

But we will not forget the pain you endured,

We will not forget the unfairness and cruelty,We will now listen

We will now listen

We will now listen

Image (top) by Anna Sanders (grade 8)

Lesley Machon is a junior high language arts teacher. As a globetrotter who has taught, learned, and volunteered abroad, she continually cultivates a passion for social justice advocacy in her work. She involves herself in many projects committed to fostering greater inclusivity and deeper understanding, both cross-culturally and trans-culturally, and finds herself at home in the many intersections between people and place.