Felicia Rose Chavez is an award-winning educator with an MFA in Creative Nonfiction from the University of Iowa. She is author of The Anti-Racist Writing Workshop: How to Decolonize the Creative Classroom and co-editor of The BreakBeat Poets Volume 4: LatiNEXT with Willie Perdomo and Jose Olivarez. Felicia’s teaching career began in Chicago, where she served as Program Director to Young Chicago Authors and founded GirlSpeak, a feminist webzine for high school students. She went on to teach writing at the University of New Mexico, where she was distinguished as the Most Innovative Instructor of the Year; the University of Iowa, where she was distinguished as the Outstanding Instructor of the Year; and Colorado College, where she received the Theodore Roosevelt Collins Outstanding Faculty Award. Her creative scholarship earned her a Ronald E. McNair Fellowship, a University of Iowa Graduate Dean’s Fellowship, a Riley Scholar Fellowship, and a Hadley Creatives Fellowship. Originally from Albuquerque, New Mexico, she currently serves as the Creativity and Innovation Scholar-in-Residence at Colorado College. For more information about The Anti-Racist Writing Workshop, and to access a multi-genre compilation of contemporary writers of color and progressive online publishing platforms, please visit www.antiracistworkshop.com.

Amanda Volel interviewed Felicia Rose Chavez by Zoom on January 28, 2021. Both were sheltering in place due to COVID-19; Amanda in Queens, New York, and Felicia in Colorado Springs, Colorado.

What might we learn if we swiveled our heads at the crossroads, inviting discovery into our periphery? If the way it’s always been done hurts and marginalizes a subset of our students, how might we adapt our habits to actively achieve plurality?

—The Anti-Racist Writing Workshop: How to Decolonize the Creative Writing Classroom

AV: While reading your book, I often thought that there were two audiences being addressed, or maybe multiple. Can you talk about who your intended audiences are in the book?

FRC: Initially, I’m talking to myself. I’m leading myself through my own journey, because the book necessitated a personal element to shed light on the pedagogical elements. I teach the way I teach because I’ve lived the life I’ve lived. So, in order for me to understand my own approach I had to go backward. In The Anti-Racist Writing Workshop, there are prompts and surveys for readers to assess where they are in their own teaching and learning trajectories. I couldn’t ask that work of readers without asking it of myself first.

This book is also a gift for people of color in this white supremacist patriarchal educational system, who at a very young age internalize that something’s wrong. So often we believe that we’re the thing that’s wrong when in fact it is the system itself that is so damaging and toxic. I want this book to be an offering to those of us who can feel validated by it, who can say “yes, you’re giving words to that feeling that I’ve carried around for years,” just as others did for me on the page.

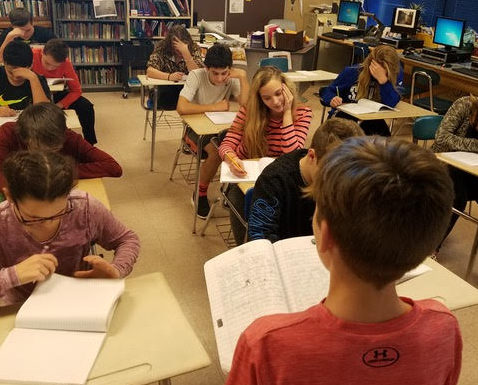

I wanted to invite educators into dialogue who want to honor all the students in their classrooms. My hope is that the book serves this dialogue across the educational spectrum. I have letters from third grade teachers, middle school teachers, high school teachers and directors of MFA programs, who are saying, “I can see how I can use this text” and it’s very exciting for me because it broadens the conversation. The impetus is change at all levels.

Lastly, I am reaching out to writers and saying “hey, it’s okay to be vulnerable” and “it’s okay to have insecurities.” I mean, so much of our writerly culture is this masculinist attitude of “I can take it, be brutal.” How do we address that culture and bring it back to this space of love and joy?

AV: Can you talk about your decision to title the book, The Anti-Racist Writing Workshop: How to Decolonize the Creative Classroom and the role that mindfulness plays in decolonizing the creative writing classroom?

FRC: While you were talking, I was thinking back to this quote by Dena Simmons: “I am leaving so that I can feel whole, so that I can feel safe, so that I can feel valued. I have everything to lose by speaking my truth.” Those words really hit hard. You mentioned safety and feeling safe, and that’s such a privilege for so many of our white students — to be able to pursue higher education and feel safe, to feel accepted, to feel reflected among their faculty and reading material, to feel validated and valued.

The fact that students and faculty of color feel suffocated and suppressed necessitates decolonization. It necessitates a reclaiming of a global worldview. It makes no sense that academia, of all places, in which we are charged with more complex thinking, is so narrow and biased in its approach. The creative writing and arts departments present the greatest irony in that they can’t come up with a better way. We’ve got these great creative minds employed by these universities and colleges and yet those same creative minds can’t direct that creative energy toward dreaming up a new space that is fairer and more equitable for all of its students. There is a charge to decolonize these spaces, to broaden our interpretation of how we can read and write, to engage each other in these classroom environments.

I will say everyone hated the title for a good long time. I had people in my life who were like, “That’s a terrible title” and yet, I just stuck with it. As Haymarket was preparing the galleys, a normalizing of the term “anti-racism” also emerged. At the time I was in Louisville, where there was a massive uprising around Breonna Taylor’s murder which had “antiracism” in the mouths of everybody. Suddenly then, the title became more popular.

We live racism. It’s part of every one of our narratives. There’s no separating it out no matter what fear that we’re working in. . . . To try to distance ourselves from racism is a falsehood. While it may feel productive in certain instances, it’s ultimately damaging.

I do think that it is a bold statement that makes people pay attention: “What does ‘anti-racist writing workshop’ mean and does it imply that my workshop is racist?” That’s the quick thinking that I wanted the reader to take on. The idea of decolonization necessitates work; it’s not something that might happen if we passively read the book and educate ourselves. Instead, it’s a series of steps that we need to take first starting with us, and then moving outward toward our students.

AV: That’s wonderful. What you just brought up brings me to a moment in the book where you write a letter to yourself. I felt like this letter was an exercise in the importance of practicing the vulnerability that we ask our students to step into. Can you talk about some methods you use to ensure that your students feel seen from the beginning of workshop?

FRC: First and foremost, it is essential for students to see themselves because so much of our focus in a traditional classroom environment is outward.

Initially, we practice seeing ourselves through a lot of freewriting exercises, in which we address our own fears, preoccupations and aspirations. Reading and writing are two practices that we have been doing for years—but we don’t always have the opportunity to reflect on them as having emotional and psychological baggage. It’s important to have students be able to really see themselves—the emotional landscape around their writing practices and the habits they’ve developed in response like: “Oh, I’m not creative,” “I hate writing” or “I’ll just jam it out the day before.” How do we, in fully seeing ourselves, begin to undo those habits, unpack that baggage, let it go for a while and see how that feels. Only then do we reach outward and practice really listening to one another. We learn each other’s names, listen to how we’re doing, and listen to each other’s work without an appeal for our opinion, which is difficult for a lot of writers.

In practicing this on a daily basis—reading work that’s not ready, sharing of ourselves from a very vulnerable place, we normalize vulnerability and in doing so we build community. It’s the sort of community where we know when someone’s not present, and we miss them.

In terms of a formal writing workshop, when folks gather to read one another’s work, we center one particular artist, and that person shares a letter that they’ve written to the class. Their letter addresses their successes with the piece they’ve just written, which is a bold move. Many of us are quick to condemn the piece we’ve just written but it’s important to practice seeing the successes in your own work, even when it’s not ready. They talk about the challenges that they faced, the vision that they have for a future draft, recognizing that this is a process, and that it is in no way a finished product that we’re discussing. Then, they guide the conversation with craft-based questions that are most important to them. In this way, we can see how this particular writer wants this piece to evolve into their future vision. We adapt our own feedback to best support that writer. It brings an immediate sense of camaraderie that is quite beautiful in action.

AV: In your book you cite this June Jordan quote: “As a teacher I was learning how not to hate school, how to overcome the pre-determined graveyard nature of so much formal education.” You say the book revealed you to yourself like a treasure map. What effect did finding writers like June Jordan have on you?

FRC: June Jordan, Gloria Anzaldua, Cheri Moraga, Toni Cade Bambara. I needed mentors and guides. I needed validation and soul food. I needed to be seen but I didn’t come across these authors until I was in my early 20s. It took a long time for me to feel acknowledged in text. I was an English major. I was a voracious reader and yet I didn’t see myself represented on the page. When I came across my own reflection in their words, it was a powerful feeling. I would cry and feel touched in a way that no text had ever been able to access that depth of emotion before. I also experienced anger when I encountered these women because that’s the moment where you realize it’s not just me.

AV: In the last few years, I also returned to writing to break with what you call in the book “the matrix of silence.” Can you talk about the matrix of silence that traditional writing workshops tend to enforce and by that extension white supremacy creates for us?

FRC: I think the traditional writing workshop engages in a powerful matrix of silence through this guise of neutrality, objectivity and universality. It’s a race-based writing workshop. It’s a white supremacist writing workshop in which white male writers are hailed as “master” and students are expected to not only honor those literary heroes but to mimic them. Within MFA programs themselves, there is a majority of white students and almost entirely white faculty. These are the folks who uphold whether your writing is truly “literary.”

The traditional writing workshop uses silence—silencing of writers of color throughout history, and silencing of students, as a tool to maintain domination, and to maintain control. We shun writers of color in order to prevent them from succeeding on their own terms. We’re not allowed to have a valid voice. It’s devastating.

I hope that this book along with “Craft in the Real World” by Matthew Salesses and “A Stranger’s Journey” by David Mura, enlighten us with opportunities for change. So often people will say, “Oh well, that sounds like a good idea, but I just don’t know what to do.” Here’s exactly what to do, so let’s do it now. It’s no longer acceptable to use silence as a tool.

AV: In your book, you talk about experiencing art workshops outside of the creative writing department and their importance in finding a new writing workshop pedagogy. Can you talk about your experiences watching dance mentors and visual artists? What did you learn from those workshops that was missing from traditional writing workshops?

FRC: I felt so ostracized by my own program that I couldn’t even stand the thought of engaging in another writing workshop. I started to enroll in different classes as a graduate student. I explored what it was like to be in photography, theater, dance and bookmaking classes. A lot of my multimedia work ended up featured in these intermediate art classes where they embrace the boldest workshop ethos that I hadn’t yet been exposed to. I remember the sheer bravado that these filmmakers exemplified; they showed a real belief in the worth of their work and they were unwavering in the face of criticism. They were so empowered to speak back to their workshop community and shut someone down when they no longer wanted to hear about a point by saying, “No, I like it the way it is.” Dance and theater introduced me to the Liz Lerman method, an artist-centered model in which the student moderated their own feedback session which was equally stunning to me.

I engaged in workshops that were only question driven. It was a conversation about process over the product itself. So much of writing workshop is about making something and then sacrificing that thing to the critics instead of reflecting back on the creation process. But this workshop environment was about what was working in the piece and that’s where the conversation stopped. It felt incredibly meaningful to bring in something uncertain and to leave with a map of what to pursue without hating the work or hating myself. All of these variations on the workshop existed at the same university and yet, I was so siloed in the English department that I thought it was the one and true way.

Within my own classroom, I try not only to nurture and mentor this sense of inspiration, but also this confidence in owning the identity of writer. Not just being a writer, but writing in my own voice, in my own way, in my own words.

AV: One thing that really excited me about your teaching practice is that it has baked into it an awareness of students’ emotional needs. Can you talk about the effects of mindfulness practice on your students?

FRC: If writing is about exercising voice, and we expect every single one of our students to do this—how is it possible for them to exercise voice without them first trusting that voice? We can’t teach them that trust. We can teach them to fake it. We can teach them to please us and adapt to our preferences. But it takes more time, energy and effort to teach them to trust in themselves. So, this emphasis on retreating inward to reflect on our emotional relationship to exercising voice helps each and every one of us to trust ourselves.

I think the dynamic between ‘student and professor’ shifts into ‘student and artistic ally’ when we’re able to have honest and open dialogue about what the student is feeling, about how workshop went, how their writing is going, what they’re writing and/or what their needs are. When we have this open exchange, the student is better able to separate those emotional needs from the requests for the professor, or the ally.

I say, “how can I best help you?” and they can articulate that separate from how they’re feeling so that I’m not serving the role of validating them. I’m not approving or disapproving of what they’re doing. Instead, I point to resources. We can tamper the rising emotion by identifying it: that’s defensiveness, that’s anger, that’s sadness, and those are the things that they grapple with in the artist statement or one-on-one conferences. I say, “Let’s talk about how voice functions in the piece” and then we focus on the practical craft elements as it pertains to the writing. So there is a separation that happens, while at the same time honoring the holistic person and process at play.

AV: I hear you talking about being a student’s artist ally, and I really loved that term. I’m wondering what remains for you of the academic world that you first navigated, and what are you witnessing is starting to give way to newness that’s giving you hope in education?

FRC: There’s a fatigue among faculty of color. They are worn down, they’re angry. They’re overworked and overstretched in so many capacities. Now there are maybe a few more faculty of color than there were when I started my own undergraduate and graduate journeys, but the reality is still the same. Professors of color have taken on so much additional labor. They’re tokenized within the academic community and sought out by students of color as a refuge. Being the sole mentor or the sole dissident voice is exhausting. That’s unpaid labor, just as our students take on that same labor within the classroom of having to explain racism, explain sexism, explain classism. Sometimes they just shut down and say I shouldn’t have to teach you that.

I’m not here for the extra labor that is still embedded in academia. But students do give me hope. I quote their letters in the last chapter of the book with purpose. There are so many students gathering, protesting, and formalizing their protests into these articulate letters, these beautiful works of art. It’s happening all over the country. I think students are getting hip to the fact that we are their employees. I say this to my own students. You are paying for your educational experience, you have every right to own it and individualize it. Speak up and self-advocate. Everyone around you will try to convince you that you are not in a position of power, but the reality is that you are providing my paycheck and I am responsible to you. The power that they have when they gather and speak out is exceptional and we could expand on that, explode that, and revolutionize academia.

AV: Can you talk about your relationship between your craft as a writer and your craft as an anti-racist educator. How do they speak to one another? Are they separable?

FRC: I don’t believe so. At a conference where I presented a chapter of the book early on, one person said, “Oh, I understand what you’re doing. This is a deeply human approach to teaching.” I really loved that because it felt so true. To see one another, to hear one another, to learn from one another and celebrate one another is deeply human. That’s an approach that I like to carry out throughout my life and it is also something that has been incredibly difficult to receive.

I think that the book is a valid representation of me as a whole because I don’t see a separation between the writer, the woman and the teacher. We live racism. It’s part of every one of our narratives. There’s no separating it out no matter what fear that we’re working in. I’ve had the privilege to write and exercise my voice and say, “It’s okay to address this”—to be all of my many selves. To try to distance ourselves from racism is a falsehood. While it may feel productive in certain instances, it’s ultimately damaging.

AV: I would be remiss if I didn’t ask you about your decision to incorporate writers of color who have been outed as abusers. What you would say to your readers who are survivors, to those who see those names and ask why?

FRC: It’s a great question, and it’s a controversial choice. Sandra Cisneros’ House on Mango Street was everything to me as a young person. To hold that text in my hands and be in conversation with home was a big, meaningful moment for me. Likewise, Junot Diaz’ “MFA versus POC” in the New Yorker provided the experience of feeling seen. It was so bold and so public, so how dare you, that it made a lasting impression on me. I carried those authors with me in my own life journey. When I chose to include them, I did so in context. When we talk about the canon, about our beloved and cherished white Western authors, I’m not advocating that we eliminate them altogether as though they do not exist. I’m arguing that we contextualize them. They wrote this. This is useful but they also did this, and we need to address that now.We can’t eliminate them from our view. They exist still and they’ve contributed to our collective culture.

The more that we get in the practice of contextualizing every author that we introduce in terms of their identity politics and the complex history that accompanies them on the page, the more we enrich our literary integrity, in my opinion. We need to have open conversations about the multi-dimensional aspects of the writer and the writer’s work on page. So, that was an attempt to model that practice in a quick nod.

AV: I’m thinking about the canon in this moment, and what it does to our collective memory. What you’re saying just reminded me of a time when I was in high school reading Edwidge Danticat. I was reading one of her books aloud in class and I remember my voice was shaking. I was reading an excerpt about the murder of a Black person during the 1930’s Parsley Massacre in the Dominican Republic. It was a pivotal moment for me of being present with my own generational trauma in a public setting and it shed a light on what writing could be. It said to me, here are the narratives that have been intentionally left out so that racism can continue to dehumanize people of color and black people especially.

I noticed that in the book, there is a trail of quotes by writers who have also dedicated their craft to post-colonial and collective healing. Can you talk about the process of spending time with these writers that you bring into your book? How did you pull together this reading list that people can go back to and use? How did you construct the anti-racist writing workshop reading list that’s on your website?

FRC: I wanted to present this ever-changing community of folks, without falling back on the same five elders that we consistently honor. I ultimately decided that I wanted [the reading list] to be a living document, something that exists digitally on the Anti-Racist Workshop website. I invite people to not only draw from the list as a multi- genre compilation, but to add writers that they love to the list or add themselves. There’s so much angst that we carry around as writers of color because there’s so few of us who actually progress in the ranks and so there is this competitiveness. What would it look like if we could just celebrate one another? The poet Allison Rollins helped me to compile the living document. I’m so grateful for her expertise as a queer Black librarian and writer.

The fact that we might be afraid of change misses the point. An anti-racist pedagogy decenters authority and decenters whiteness so that we are no longer at the center of the discussion. It’s not about us. It’s about our students.

I kept my own mentor authors on my nightstand. It was a tall stack, but they stayed with me throughout the writing process, always handy. Upon quick glance they helped me to see beyond my own petty insecurities. They inspired me to push me further—the vulnerability that so many of these writers exhibit gives power to their voices.They lent me their strength. I say to educators who are fearful of trying a different approach, “Of course there’s fear involved in change but let’s be emboldened by all who’ve come before us.”

AV: From your own teaching experiences, can you talk about what you feel is missing from the MFA for students to graduate from the program being fully empowered to move forward in the world as writers?

FRC: There’s many ways to answer that question. I think that the system as a whole is troubled and has a lot of room to grow. Within my own classroom, I advocate for students to adapt a writing habit that continually seeks inspiration without needing an assignment or a directive, which is I think the role we become accustomed to as students. As writers, it’s essential that we find our own sources of inspiration, trust our instincts, and pursue it. I teach this skill in a class called “the inspiration lab” in which students bring the thing that they seek out when they’re down or troubled, whether it be a rap album, a comic book or a Dickens novel. They bring in whatever it is that they seek out. That’s the challenge of being a professional writer, after all. When you forego the assignments, when you forego the community, where do you stand in your trust, in your own intuition?

When we finish the MFA, so many of us leave juggling outrageous teaching schedules. Some of us are adrift for a while, figuring out the next step. And so, how do we hold on to inspiration as writers? The trick is to trust ourselves in what we’re excited by and pursue that. The trick is to truly believe that we are writers. I think that the MFA program is confusing for a lot of students in that they’re admitted to a program and that’s a point of pride and yet a lot of their energy is spent questioning whether or not they’re any good.

Within my own classroom, I try not only to nurture and mentor this sense of inspiration, but also this confidence in owning the identity of writer. Not just being a writer, but writing in my own voice, in my own way, in my own words. There’s great power to having students leave saying, “I am a writer and I’m very proud of myself,” because that’s not something that’s easily shaken once you achieve that foundation. I would say those are the two largest points of growth for an MFA program is not to be handed down some canonical source of inspiration or this is what you should like, but instead pursue it and then to truly celebrate ourselves as writers without needing the affirmation of the literary community.

AV: What can institutions learn from The Anti-Racist Writing Workshop pedagogy and how from this pedagogy can institutions own the responsibility of showing up more for students and faculty of color?

FRC: These institutions are violent towards their students, their students of color, their working-class students and their queer students—there’s a violence that’s inherent to this system of oppression. It’s so deep rooted that it necessitates saying it aloud. It necessitates action and saying, “Here are the steps that we are going to take and not just us in the administration or us in the Student Center, but every single one of us on campus, including our students and our professors.” It necessitates listening.

You spoke about that last chapter the book in which I quote so many beautiful letters from students who have had enough, from students that are saying, “Stand up for me, college! Stand up for me, university! Why do you allow this violence, again and again and again and just apologize afterward?” The response they receive is a nod and then we continue on.

There’s an urgent need for these institutions to correct their legacies of abuse. It’s not going to happen without every single one of us educating ourselves and reflecting on our own biases. This is from the president of the college down to your teaching assistants. Every single one of us has the responsibility to our students to assess our own behavior, traditions, inheritance as instructors and our own bias and to correct it in order to change course so that we can truly serve our young people.

AV: What is on your heart to say, at the end of this interview?

FRC: It is important for me to reiterate that the anti-racist pedagogy is essential to each and every one of our classrooms regardless of the multicultural composition of our students. No matter if you teach all white students or if you teach within a diverse learning environment, it is essential to pick up, practice, study and engage with anti-racist pedagogy. It is easy to narrow our perspective. Again and again, I hear white male educators who say, “I’ve never experienced that. I highly doubt it exists. Is racism even real?”

Part of the practice is addressing and reflecting on our own inherent bias. We are responsible to our students. This is not a matter of a contained classroom experience. This is a matter of empowering all our students to exercise voice through the rest of their lives. The fact that we might be afraid of change misses the point. An anti-racist pedagogy decenters authority and decenters whiteness so that we are no longer at the center of the discussion. It’s not about us. It’s about our students. We are responsible for broadening our thinking so that we can cultivate the next generation to serve as global citizens. The responsibility runs deep and we need to own it. Let’s not let fear, denial, despair, rage stop us. Let’s move forward in solidarity to create something that will have lasting implications.

Amanda Volel is a poet and educator from Queens, New York. She has an MFA in Creative Writing from Sarah Lawrence College. She joined T&W in December 2018 as a teaching artist and currently works as a communications & development associate.