“One, two, three, four, five, six, seven, Eight MMM-Masks in my bank account, in my bank account,” echoes down a corridor in New York City’s American Museum of Natural History. The lyrical reinvention of 21 Savage’s “Bank Account” is sung by a middle school boy from PS/IS 218 Rafael Hernandez Dual Language Magnet School in the Bronx. With him are 20 of his classmates and their chaperones—an art teacher and a poet-in-residence from Teachers & Writers Collaborative.

Today, the group enjoys an hour-long field trip. With no time to waste, they rush past the museum’s infamous taxidermy dioramas toward the Northwest Coast Hall, which houses what the group has come to see, a collection of ornate indigenous tribal masks.

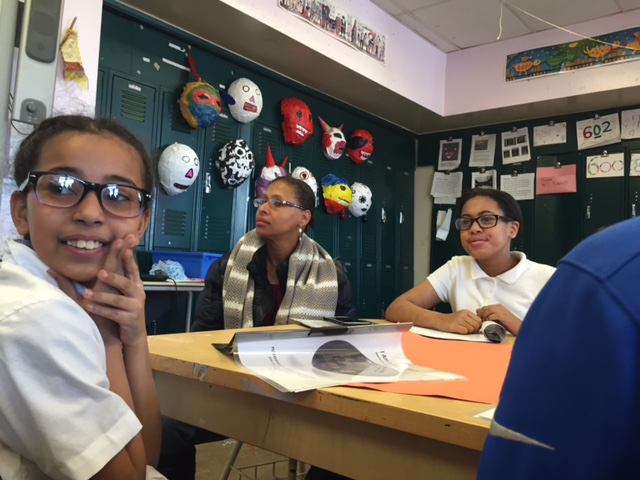

These masks have become the centerpiece of the T&W field-trip program at PS/IS 218. This year, the school partnered with two poets-in-residence, Jane LeCroy and Samantha Facciolo, both of whom taught poetry in three sessions at the school, and one field trip to the museum. By referencing the artistic craft present in indigenous mask work, the T&W teaching artists aim to have students writing poetry that uses similarly expressive literary techniques of metaphor and symbolism.

The students appear entranced when they enter the hall. The space is partitioned by giant carved totems, taller and wider than most trees in New York City. In between the totems are small gallery spaces where tools, ornaments, and wooden masks hang on display.

At first glance, the masks take on a life of their own. They are colorful, bold, overwhelming, and entirely distracting. However, the group manages to collect promptly around a bench, awaiting further instruction.

LeCroy begins the museum visit, her second day with the class, by reminding the students of two poems she read during her first visit to the school. One of the poems, “The Clans” by Richard Calmit Adams, figuratively illustrates indigenous life.

Some children whisper remembered phrases from the poem, while others point to masks in the gallery space surrounding the bench. In clandestine dialogue, one boy claims that the mask over his left shoulder “looks like the “Turkey Clan,” as described in “The Clans.” Another boy refutes, whispering back, “No, that one is the Wolf Clan!”

Next, LeCroy directs the students to find a mask they like, which they are to draw and describe by writing adjectives on a worksheet she hands out.

“The worksheet exercise is to help you brainstorm ideas and words you may want to use in your own masks and poems, when we come to create them in the next two weeks,” LeCroy explains.

Mary Agramonte, the art instructor at PS/IS 218, sends the students off, with a deadline of 40 minutes, and a final reminder to each student to select a mask they find visually relatable.

Relatable is the emotive term for this outing. In addition to finding words that describe an unfamiliar culture, these students are tasked with identifying the artistic devices that indigenous tribes used to express their daily life.

This assignment seems advanced, reflexive, even daunting for a group of adults, let alone middle-schoolers. However, the class disperses, absolutely unfazed by the assignment at hand.

At first, pairs of students fight over the most prominent mask in each gallery alcove. A few other students wander in circles, eagerly searching for a mask overlooked. Soon, though, the arguments and pacing subside.

For 20 minutes, each student quietly scratches at their page, replicating their muse as precisely as possible. Then scribbles sound, and lists of adjectives fill the worksheet pages. LeCroy and Agramonte travel around the hall, checking in on each patch of students strewn across the museum floor. One boy asks LeCroy if there were masks from “new” tribes; another girl posits what it would be like if her head was as big as the warrior mask in front of her.

“Exactly!” LeCroy shouts.

In T&W fashion, LeCroy uses this opportunity to redirect the students’ attention to the empty margins on their worksheets. She tells the two students to write any words that come to mind when they imagine themselves as a part of a “new” tribe, or as a child with a big head. A few other students overhear and lean in to listen.

LeCroy notices and says, “Well, what would you do?”

The eavesdroppers giggle, spitting out answers that are creatively uninhibited and irrelevant in the way that children often do. As LeCroy tends to the next group, the eavesdroppers form a circle and begin to world build an imaginary place. According to them, this place is much like New York, except there exist only “new” tribes and children with oversized heads.

Most of the class completes their assignments before the final five minutes. When finished, pairs of students gather near the hall entrance, until everyone congregates around the bench once again. Equally excited and exhausted, the students share with one another what they’ve documented, showing off their project ideas. And just like that, the PS/IS 218 group departs, bursting with song just as loudly as they came.

In the following two weeks, these students will have produced not only a work of art, but also a poetry anthology published by T&W. More importantly, they will have engaged in a creative process that is continually challenging for most tenured writers. This process is one in which we as educators must ask ourselves: how and why must we create in new ways?

Learn more about the poetry and mask-making lessons and read anthologies from Lecroy’s and Facciolo’s classes.

Jacy Bryla is a creative writer and advocate for all things that encourage others to write and create. She is currently an MFA candidate in fiction writing at The New School and a 2017–2018 editorial associate at Teachers & Writers Collaborative. Jacy began her writing career during her undergraduate years at California State University, Fullerton where she studied political science and communications in journalism. It is also worth noting that Jacy was a longtime resident of the San Francisco Bay Area and does, in fact, love riding BART.