For more than a decade, Teachers & Writers Collaborative and New York University’s Creative Writing Program have partnered on the NYU Writers in Public Schools Fellowship program. In this program, three first-year MFA students who have been selected as fellows observe T&W teaching artists and receive support to further develop teaching skills and create new curricula. The writers are then placed in a creative writing residency at PS 110, the Florence Nightingale School, in New York City’s Lower East Side. Emily Wallis Hughes was a 2014–2015 NYU fellow teaching with T&W.

As I sit here on a bench on Eastern Parkway in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, with a large coffee and a Danish in a paper bag, I’m remembering where my teaching voice was made: in the heavily chlorinated, warm water of a pool in Santa Rosa, California. On one July day, in the indoor pool where young children and toddlers learned how to swim, a shy five-year-old girl in a purple swimsuit with pink ruffles cried and peed in my arms. I let her cry, and told her that it was okay to cry. I listened to her, and as I did this, I felt like I was comforting my younger self. I reminded her of the progress she had made. I lifted her up and sat her on the edge of the pool. I took a few steps back and said, “Swim to me—I know you can do it!” She dove into the water with an excellent streamline and swam towards me. I walked backwards in the water, slowly, to the opposite edge of the pool, where I took her in my arms again in a hug and said, “Look back! Look at how far you’ve swum!”

She took off her purple goggles, looked back, and giggled. Her eyes were still red from tears, but they were now smiling.

*

I’ve been in New York City for almost a year now, and I’ve been trying to re- (insert all of the words we use to say “find,” “ignite,” and “renew”) my student, poet, and teacher voices. This bench on the Eastern Parkway walking path is all hexagons, with its trees, with its families, and with its animal life. It is the place I go when I need to think. I think and write, walk and think about the upcoming week’s lesson, walk and think about my classes, walk and think about my poems, and walk and think about my reading. The words of advice from the mentors and friends I’ve found at New York University repeat themselves, and I keep walking.

There are three little birds hopping across the hexagon-filled path now—one is a bit more hesitant and shy compared to the other two, but suddenly it jumps up to the others, and they all fly up into the tree to my right. These three little birds are my voices. Sometimes one is stronger and more assured of itself. Sometimes the less-confident one follows the others for a while, and then becomes capable of leading again. Sometimes all three birds are equal and collaborate in joyous harmony. It has been harder for me to find these moments since moving here, but I’ve been able to find more of them by walking, listening, and remembering. I’ve been growing, and I watched my students grow as well during my residency. My fourth-graders had never written poems before, but Mr. Ditzion and I were both impressed with their lively imaginations.

In an adaptation of Dorothea Lasky’s “Red” exercise, I saw the children’s writing become even more wild and free. I began by allowing the children to pick any color—it could be a favorite color, a friend’s favorite color, or even a least favorite color. They began a list of what they recognized as that color in everyday life; then continued on to what they imagined and wanted to be that color; then further on to what emotions, thoughts, and concepts they imagined that color to be. As I read through their poems, I was amazed to see what emotions were red, purple, yellow, blue, violet, and orange.

The students’ contemporary haiku, inspired by Matthew Rohrer’s, also revealed aspects of their psyches, which I was glad to see emerge. The children picked an animal—any animal, whether real or fantastic—and imagined what it would be like for that animal to live in New York City. I saw my students choosing animals that represented their own behavioral characteristics, and this helped them find new ways to share their visions of life in our everyday world, here in this city, which is at times, in all of its reality, its own kind of surreal wilderness.

My students were in love with the surreal, so as we began focusing on revisions for the anthology, I encouraged them to combine their color poems and haiku. I was happy to meet a “purple and black goat who wears gems” and a “tigress with green eyes, who smells like wildflowers”!

*

In my graduate Craft of Poetry class this semester, I came to see the barriers that I had made to keep myself from speaking, and again, I thought of a few of my students who were struggling with sharing their voices and taking risks. Later, the teacher of the class, Eileen Myles, told me, “You need to put yourself in more situations and conversations where you are challenged. It’s okay to let yourself be upset.” I asked her and my other mentors some of the same questions in their office hours. These were the same questions that some of my students asked me, I later realized: “Is this okay? Am I doing well? Should I keep doing this?” Yes, yes, and yes. “Yes, keep going!” Matthew Rohrer would say, and “Have ambition in the work!” Deborah Landau would tell me. I passed on these same words to my students when I met with them one-on-one, when I was able to look them in the eye, in order to make sure they knew that I meant what I said.

So I see now that day to day, we are giving and re-giving each other the advice of our elders, and lifting one another up when we’ve forgotten where we are and where our voices have gone.

Towards the end of one of our lessons, a fourth-grade student told me that he had lost his imagination. I didn’t know what to say at first and almost cried. I was so surprised that he would say this because I knew he hadn’t, based on his poems and his exuberant smile, his knowing eyes. I bent down at his desk, looked him in the eye, and said, warm and firm, “No, you haven’t. It’s in you, and right here, in what you’ve just written.” I could also tell that he felt like he didn’t quite fit in with the rest of his classmates, and that he felt ashamed of this. He didn’t want to write something that his classmates would make fun of him for sharing. I made a note of this, and thought about how I could remind everyone in the class that what differentiates us from one another is what makes us truly beautiful.

At the beginning of our next class, I reminded the children that it’s not only okay to be weird and different—it’s cool, actually. It’s boring, I told them, to all sound the same and act the same way. We read two poems by Hoa Nguyen and Valzhyna Mort. I showed them how these two poets are very different from one another, and yet both exhibit bold, engaging voices. If I had one more class with them before our last lesson, I would have brought poems and audio from Lucille Clifton too. I find myself wanting to learn more from her courage as I move forward.

*

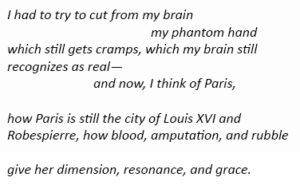

Michael Dickman sat down at the table in my graduate poetry workshop, sipping his usual iced coffee, and passed out copies of “The Arc” by Frank Bidart. Each of us read one section aloud, and each poet’s voice seemed to be, in some way, appropriately suited for the section read. When we arrived at the last lines, I caught my breath, and I thought of my voice, and what I had been holding back, out of fear and shame:

When I returned to my apartment in Brooklyn, I took the poem out again. There, in my room, the poem was lying next to me, speaking, listening, and teaching. My self was there too, but barely. It was showing a way to keep going, onward, to new worlds:

So I drew three lines. One from blood to dimension. One from amputation to resonance. And one from rubble to grace.

As I stared at these lines, I saw how my voices are walking with them, every day.

I didn’t expect to see this, nor did I expect to see what I saw in this residency: I saw again, more clearly, how our voices and bodies are inseparable.

Once we recognize where our bodies are, at any point in time and place, we can speak. This is the great work of the teacher, the student, and the artist. We teach, learn, and create in order to help one another be in a space of recognition.

Emily Wallis Hughes grew up in Agua Caliente, California. Her poems have been published in Gigantic Magazine and the Sacramento News & Review, and anthologized in Burning the Little Candle (Ad Lumen Press). She lives in Brooklyn, New York.