Serenity was her name. She was five years old and named after the Serenity Prayer, words I imagine countless Houstonians recited as a daily, sometimes hourly, mantra as we faced epic flooding in our city: God, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, courage to change the things I can, and wisdom to know the difference.

Serenity was a Hurricane Harvey survivor sitting with her mother in a long line of fellow Houstonians, waiting patiently for assistance at the George R. Brown (GRB) Convention Center. I was there as a volunteer with Writers in the Schools (WITS) to spend time with those displaced by the storm. Though I showed up to give to those in need, I found the experience gave me something quite valuable as well.

That first day, I approached Serenity to see if she wanted a free book. Serenity smiled a half-smile, nodded a half-nod. After we sat down together and read her chosen book, I asked if she might want to tell a story with me. She perked up suddenly, giving me an enthusiastic “YES!” There it was, that light. During my time with her, I learned that she had recently witnessed chaos, panic, loss, and rescue, and it showed: she wore a weariness that no child her age should carry. Still, the spark inside her was bright, undimmed by the devastation that had sent her to this downtown shelter.

It was suggested to those of us volunteering that we not push, not ask probing questions, but simply be present and allow each child to determine how to spend their one-on-one time with us. So I allowed my time with Serenity to unfold as it would and trusted she would lead us where she needed to go.

During my time with [Serenity], I learned that she had recently witnessed chaos, panic, loss, and rescue, and it showed: she wore a weariness that no child her age should carry.

When I asked if she was ready to write a story, Serenity hesitated for a moment and said, “I can’t read and write. I’m only five, after all!” I told her that was okay; she could tell the story aloud and I would write it down. She nodded and said she wanted to tell a story about an animal. I asked her what kind of animal, and without skipping a beat she replied, “A monkey!” And then she was off. I quickly scribed the story she told about a monkey named Rainbow who was tired, but happy to be playing with friends. Serenity, too, was tired. Perhaps through storytelling, she was holding onto her own happier times when she, like Rainbow, was free to eat bananas, play hide-and-seek, climb trees, run with friends, and have sleepovers. And in the midst of a sea of exhaustion at GRB, Serenity’s enthusiasm, at least, was tireless.

Writing with Serenity was a sweet reminder of the power of connection through story— the strength of one person sitting next to another, asking if they have something to share, and listening deeply to what they have to say. With each line we added to Serenity’s story, she inched herself a little closer to me until her arm met mine, and then she was leaning into me, completely immersed in our project together.

We all have stories to share, and children are natural storytellers. In times of upheaval, the things they tell us show that, like Serenity, they are also teachers, imparting lessons of resiliency and optimism in the face of hardship, like the prayer that inspired her name.

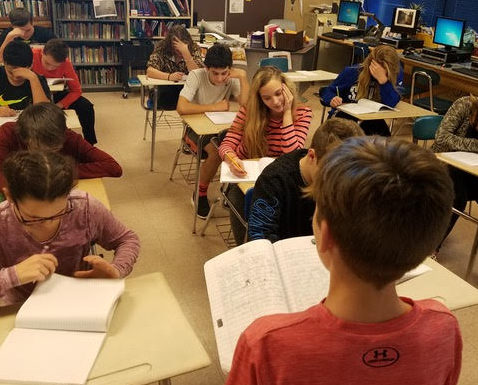

Photo (top): Pearl Reagler writing with children sheltering at the George R. Brown Convention Center. Photo by Robin Reagler.

Nancy Barnhart has been with Writers in the Schools (WITS) for 10 years. She has an EdD in curriculum and instruction from the University of Houston. Currently, she shares the joy of writing with children in classroom settings and at Texas Children’s Hospital Cancer and Hematology Center. Her poetry is published in Saudade, and she has journal articles published in Affective Reading Education Journal, Teachers & Writers Magazine, The Ohio Journal of the English Language Arts, and The English Record.