The following foreword to Kenneth Koch’s Wishes, Lies, and Dreams first appeared in the 30th anniversary edition of the publication. Now in its 50th year, the book continues to inspire teachers and teaching artists and the children they teach. Related reading: “Educating the Imagination,” a 1994 essay by Koch, and “The Presence of Joy,” Robin Reagler’s reflection on the impact of Wishes, Lies, and Dreams on her work at WITS Houston.

Koch was not a political activist, but his desire to teach poetry writing to children was radical, and the conditions were right for a breakthrough.

What made Kenneth Koch’s Wishes, Lies, and Dreams such an original and useful book when it came out in 1970 was not only that it showed that children could write marvelous poetry by being led directly into their imaginations, but also that it provided practical ideas and specific techniques for helping them to do so. In other words, it opened a door for those who had never written poetry (children) and those who had never been shown a way to teach poetry writing (schoolteachers).

In 1968, when Koch began teaching young children, the landscape of poetry teaching at that age level looked barren. There were a few signs of life, such as the work of Flora Arnstein and Richard Lewis, and more generally there was the pedagogical tradition centered on children and on a faith in children’s creativity—the tradition of John Dewey, Maria Montessori, Sylvia Ashton Warner, and others. But no one had come up with a body of practical ideas and methods that elementary school teachers could use to teach poetry writing, and therefore no one had had a widespread impact on the way children wrote poetry.

In fact, in 1968, when Koch began his work with children, the prevailing idea in many schools was that children couldn’t write poetry at all, or that if they could, it was in the form of jingles or predictable pieces about the changing of the seasons. Of course, there was the occasional child prodigy or the gifted teacher (such as Richard Lewis) who had the seemingly mysterious ability to draw poetry out of students, but generally poetry was considered too difficult and sophisticated for young children to write. Instead they were seen merely as consumers of poetry written for them by adults: nursery rhymes, nonsense poems, limericks, and poems about pets. That children enjoyed these works was a convenient but erroneous confirmation of the notion that children’s taste and abilities were miniature.

Added to this was how poetry—reading or writing it—intimidated most teachers, whose training had not prepared them for this seemingly remote and specialized art. Many would rush through the poetry unit mandated by the language arts curriculum, heave a sigh of relief, and move on to the steadier ground of spelling, reading stories, and the like.

But Koch’s work, as original as it was, did not just magically appear. Since the early part of the century, poets such as William Carlos Williams had been writing free-verse poems in simple, everyday language, and by the late 1960s it was abundantly clear that good modern poetry need not involve elevated subject matter presented in an elevated diction framed by rhyme and meter—the major stumbling blocks for children writing poetry. In education, the egalitarian notion of the “spiral curriculum”—including the idea that, as Jerome Bruner put it, “the foundations of any subject may be taught to anybody at any age in some form”—had been spreading since 1960. Though Koch had not read Bruner, the concept of the spiral curriculum was implicit in Koch’s teaching poetry writing to children, just as it had been in his teaching English at Columbia University: he had a knack for making difficult literature accessible and attractive without falsifying it or watering it down. By May of 1968, when student protests at Columbia erupted and Koch coincidentally began his work with children, the social, racial, economic, and political hierarchies of the entire country had been called into question. Koch was not a political activist, but his desire to teach poetry writing to children was radical, and the conditions were right for a breakthrough.

Koch’s early teaching diaries are filled with examples of what he later realized was at the basis of his method: “The secret way I found of making this work extremely interesting and enjoyable is that every class I taught involved trying to discover something new.”

Koch’s initial work came about when his friend Emily Dennis invited him to try teaching poetry writing to a small number of children at MUSE, a hands-on neighborhood museum in the Bedford-Lincoln section of Brooklyn, where she taught art. Around the same time, the Academy of American Poets had started a pilot program in which poets visited the New York City public schools, mainly high schools, to read their poetry and answer questions from the audience—what was called an “exposure” program. Koch wanted more. He wanted to try some experiments in which he would help the students—younger ones, in his case—to write their own poetry, in repeated classes with him over an extended period of time. The Academy found a welcoming elementary school and funded the first few months of his visits there. Afterward, and for the next several years, his work was supported by another nonprofit group, Teachers & Writers Collaborative.

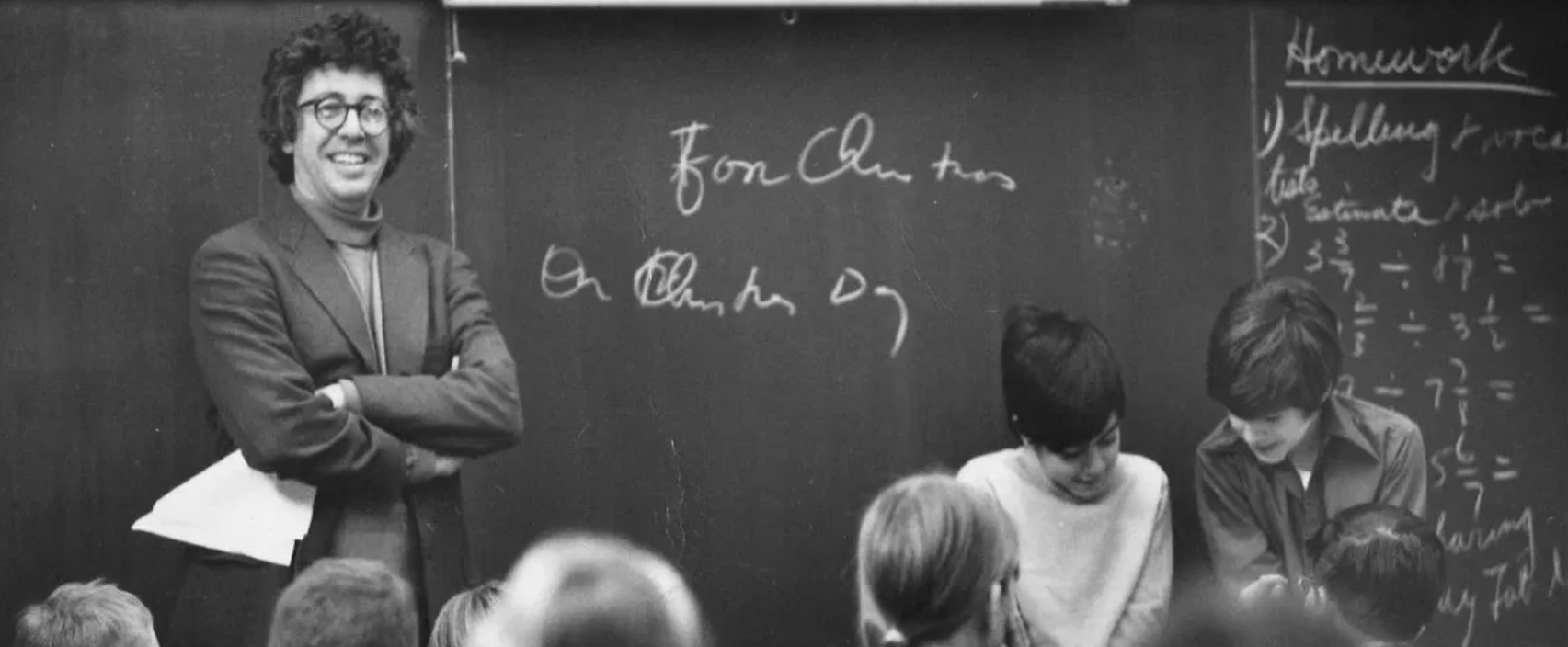

Teachers & Writers Collaborative turned out to be the perfect sponsor. Recently formed by a group of liberal writers and educators—Grace Paley, Muriel Rukeyser, Herbert Kohl, Robert Silvers, and others—the Collaborative gave Koch complete freedom, asking only that he send them accounts of his experiences in the school and examples of his students’ writing. Koch’s early teaching diaries are filled with examples of what he later realized was at the basis of his method: “The secret way I found of making this work extremely interesting and enjoyable is that every class I taught involved trying to discover something new.” Koch’s enthusiasm for discovery and his high spirits infused his students with a zany energy, which in turn redoubled his enthusiasm. Behind it all was the fact that he was a poet who had a talent both for the pleasures of poetry and for finding ways to allow others to discover those pleasures for themselves.

Koch quickly learned a lot from the students and teachers at P.S. 61, noticing what worked and what didn’t, modifying his approach as he went. And he began thinking about writing a book about his experiences at that school, as a guide for others and as a way to present the fresh, surprising, and moving poems his students had written, and that others could write too. This book turned out to be Wishes, Lies, and· Dreams.

The first public notice of Koch’s experiences at P.S. 61 came in the February 25, 1969, issue of the Wall Street Journal. But it wasn’t until the following year that Koch and his students began to receive more concerted attention, first by giving a public reading at New York’s 92nd-Street Y, the same place where famous contemporary writers read their work. The April 9, 1970, issue of the New York Review of Books printed the introduction Koch had written for Wishes, and the April 6 issue of Newsweek carried an article on Koch and his “slum children” (a designation that prompted the indignant children to fire off protest poems to the magazine). The May 15 issue of Life magazine carried a lovely column entitled “On a Sailboat of Sinking Water” (a quotation from one of the student’s poems).

But the impact of Wishes, Lies, and Dreams was more persuasive than simply that of a book that is read and enjoyed. Around the time of its publication, state arts councils across the country began hiring poets to conduct writing classes with young people in the schools. For a great number of these poets, Wishes, Lies, and Dreams was both a handbook and a godsend, because no other such guide was available.

The year before, several major New York publishers had rejected an initial version of Koch’s manuscript. Koch’s friend Maxine Groffsky, who was a sort of talent scout for a new and little-known publisher called Chelsea House, glowingly described his book to them. Chelsea House snapped it up and brought out a hardcover edition in the spring of 1970. Although the pieces in the New York Review of Books, Newsweek, and Life helped with initial sales, the reviews came in slowly. When they finally arrived, they were unanimously enthusiastic, along the lines of “I wish every grade school teacher in the country would run out and read Kenneth Koch’s Wishes, Lies, and Dreams. If many of them took Koch’s advice seriously we would have at the very least a poetry revolution, not to mention the possibility that a lot of kids would start having a good time at school” (Allen Wiggins, Cleveland Plain Dealer), and “Wishes, Lies, and Dreams ranks with the best literature on education” (Karen Malpede, The New Leader). Koch and some of his students found themselves on David Frost’s national television show; then Koch was interviewed by Barbara Walters on Good Morning America. WNET Channel 13 featured Koch and his students, as did various radio talk shows. The National Endowment for the Arts Literature Program commissioned a documentary film showing him at work at P.S. 61, and Spoken Arts brought out a long-playing record of the children reading their poems. For the next four or five years, Koch conducted demonstration classes in schools around the country and gave keynote speeches and talks at venues such as the annual convention of The National Council of Teachers of English.

For a book about what seemed to be a modest subject— children writing poetry—the media splash was remarkable. Sales of the hardcover edition took off, and within a year the book’s distributor, Random House, brought out a Vintage paperback, after which it was reissued as a Harper & Row Perennial edition. It has been reprinted many times, and the book continues to be discovered by new generations of teachers, parents, and others interested in poetry. The book’s history in its first five decades allows us to start thinking of Wishes, Lies, and Dreams as a classic.

But the impact of Wishes, Lies, and Dreams was more persuasive than simply that of a book that is read and enjoyed. Around the time of its publication, state arts councils across the country began hiring poets to conduct writing classes with young people in the schools. For a great number of these poets, Wishes, Lies, and Dreams was both a handbook and a godsend, because no other such guide was available. These poets not only had their many thousands of students write poems about wishing, lying, and dreaming, but, inspired by Koch’s example, they went on to invent their own approaches and poetry writing ideas. Many of these new ideas were presented in Teachers & Writers magazine, published by Teachers & Writers Collaborative and read by adventurous creative writing teachers all over the country. (Koch himself continued to publish new essays there.) Eventually, even traditionally conservative teachers’ colleges and textbook publishers relented, and Koch’s general approach and many of his specific assignments became accepted practice.

Of course, every success generates its own backlash. Critics of Koch’s work said that his method was too formulaic, or that it didn’t encourage children to write poems of social commitment, or that the kid’s poems sounded like Koch’s. One particularly sour critic wrote a whole book to show that children can’t really write poetry—that is, according to her definition of it. There are good answers to these objections, but what the critics overlooked was that Koch—a champion of the free imagination—never advocated lockstep methods. They also conveniently forgot the vacuum of teaching poetry writing to children that prevailed before Koch single-handedly awakened the country to the dazzling possibilities.

After Wishes Koch wrote or co-authored five more books about poetry—Rose, Where Did You Get That Red?; I Never Told Anybody; Sleeping on the Wing; Talking to the Sun; and Making Your Own Days—in addition to new adaptions of Wishes in French and Italian. Teachers love Koch’s work, because it is useful and magical; parents, poets, and general readers also like it, because it is optimistic, reasonable, energetic, and sheer fun. Readers are heartened to learn that writing poetry is natural and healthy, something virtually everyone can do, even small children. Over the decades, readers of Wishes, Lies, and Dreams have been doing silently what Koch’s students did every time he entered the classroom: shout “Hooray!”